Georgism & Natural Resources Taxation FAQs

A Painstaking Attempt To Answer Everyone’s Questions

1. Introduction (Start Here)

This FAQs is a work in progress. It was created by compiling the following FAQs pages, and adding my own (Zero Contradictions) contributions and edits to the FAQs.

- r/Georgism Wiki FAQs.

- Justopia.org’s A Revised Geoist FAQ, based on Todd Altman’s GeoLibertarian FAQs.

- Prosper Australia’s FAQs

- HenryGeorge.org’s FAQs

- LandTaxation.org’s FAQs

- The Henry George AI Robot.

Readers may be interested in Mark Wadsworth’s Killer Arguments Against LVT… Not. Is probably the most comprehensive on the entire Internet, even moreso than this one. However, I dislike its CSS, some of the wordings, and many of the arguments that it makes or prioritizes when arguing for Georgism. It is remarkably thorough, but it could still be greatly improved. Unfortunately Wadsworth is deceased (RIP), but if I have the time, this FAQs may possibly someday outshine his impressive work. Perhaps some AI could even generate something that’s even better with the best of both worlds.

Many of the questions on this page address the same objections and misunderstandings, so it may feel repetitive and redundant to read all the questions and answers on this page. If you would like to read an actual essay explaining what Georgism is, then we recommend reading: Georgism Crash Course.

Since this FAQs page aims to be the ultimate Georgist FAQs page on the entire Internet, it’s still a work in progress. Questions that have been taken from sections of other FAQs files, but whose content has not yet been modified to be properly formatted and written in the same concise post-overton style as everything else on this website are marked with “-N” at the end of the question. Eventually, they will be copy-edited to give a consistent feel and the most concise information dense style as the rest of the FAQs.

Disclaimer: I haven’t read the book yet, but Critics of Henry George is said to have a very comprehensive documentation and analysis of all the major critics and criticisms of Georgism. It may have many important ideas and arguments that are not addressed on this page.

2. Why are natural resources taxes better than other taxes?

Most existing forms of taxation punish productivity. Most existing forms of taxation are complex, ad hoc and create opportunities for corruption and tax evasion.

Although natural resource taxation has some complexity, it is much simpler than existing forms of taxation. There are a relatively small number of physical inputs to production, and they are relatively easy to audit and control. Natural resource taxation would be much simpler and fairer than applying taxes to every economic transaction, which is how the current system works.

2.1. Why would Georgism tax natural resources, and not just land?

By taxing the economic inputs of the economy instead of the economic outputs, there would be incentives to use the inputs (Natural Resources) more efficiently, and we should absolutely want this since there is a fixed, finite amount of valuable land and natural resources on Earth. Likewise, people wouldn’t get penalized for generating greater economic outputs.

Although location value taxation would be the main most dominant form of taxation, the taxation of the following would depend on how large the demand for those resources is, relative to the supply:

- Mineral Deposits

- Forests

- Fish Stocks

- Geostationary Orbits

- The Frequencies of the Electromagnetic Spectrum

- Reproduction Licenses

The economics is pretty easy to understand, provided that one has an understanding of supply and demand.

2.2. Why are natural resource taxes better than a progressive income tax?

Income tax is based on income earned by labor or investment. If you work hard and well, or invest wisely, you will pay more income tax. This punishes productivity, and it makes labor more expensive. Income Tax is the sort of thing you would come up with if you were specifically trying to make the economy less efficient.

Income tax also requires individuals and companies to be accountants and keep track of financial minutia — or lie about them.

2.3. Why are natural resource taxes better than a flat income tax?

A simple flat tax would be relatively easy to assess compared to progressive income tax, but in most countries the income tax is very complex, with many loopholes and subsidies.

A flat income tax may have less harmful effects than a progressive income tax, but it would still punish productivity, and it would make labor more expensive nonetheless.

2.4. Why is natural resource taxes better than value added tax / sales tax?

VAT would reduce economic activity by decreasing sales in the economy. Consumption taxes also punish productivity, although not directly. All income is eventually used for consumption of some kind. So, a tax on consumption is a tax on income, and thus a tax on production.

Value-added tax is very complicated, because it requires a full accounting of revenue and the costs of production. Sales and value-added taxes are often ad hoc, and vary from one jurisdiction to another.

Sales tax requires businesses to record every sale, so it incentivizes them to not record every sale. By comparison, it is way easier to hide purchases and transactions than it is to hide land, especially since those purchases and transactions would be private knowledge, but not public knowledge (unless you make an authoritarian law mandating that everybody’s transactions be made public, but even then, people would still find a way around that). This is yet another reason why VAT is more prone to tax evasion, and would require significantly more paperwork than LVT.

More Information: Why FairTax is a Bad Idea.

2.5. Why should we implement land value taxes when we already have property taxes?

Property Taxes make housing less affordable, whereas Land Value Taxes make more affordable. Property Taxes reduce the supply of housing (by making it more expensive to build housing), and since the tenants thus have fewer options/alternatives to choose from, this enables the landlords to pass the Property Taxes onto the tenants. This wouldn’t happen at all with LVT though, because LVT would incentivize landlords to build more housing per square foot and they wouldn’t get penalized for creating new floors on their land. Since LVT would increase the supply of housing, the tenants would have many options to choose from in this buyers’ market, so LVT would not get passed onto the tenants.

People who own buildings wouldn’t be disincentivized to not upgrade them anymore. If property taxes are abolished, then people won’t get penalized for renovating their properties.

Property taxes also tax economic improvements to the land, which disincentivizes people to renovate their properties and creates the aesthetics similar to urban decay. Taxing economic improvements (which require human labor) makes the economy less efficient because that would effectively be a tax on productivity, and thus higher undesirable.

Furthermore, property taxes don’t bootstrap prices within the economy, nor do they conserve natural resources.

2.6. Why don’t we impose reciprocal import duties? -N

This solution and any other which makes goods more expensive to the local consumer simply reduces the market for the imported product, and increases the price of the home grown substitute. The only winner there is the producer of the protected product, who, with less competition can boost his price without having to worry so much about service or quality. He has a captive market. Tariffs and duties punish the consumer by inflating prices and reducing choice and quality.

3. General Questions

3.1. What do Georgists think about Private Property?

- We believe that people only have a right to the fruits of their labor.

- We support private land possession, and detest private land ownership.

- Private land ownership enables rent-seeking. Rent-seeking is bad for a society because it does not generate wealth.

If I make something with someone else, do they have just as much ownership over it as me?

That’s a game theory problem. The workers need to come to some agreement about how much value they each deserve from making the product.

How does one lend enough land for everyone to get access to it?

The state don’t lend land to everyone, because not everybody needs to possess land in order to work.

Is it realistic that every citizen of a country can rent land?

Not really.

Are there more than one renter for each land plot?

There can be. It would depend on who is assigned to the land title.

3.2. Why should landowners pay land value tax?

- There is an interesting split between geoists who believe those who create land value are obligated to receive it and geoists who believe those who occupy land value are obligated to return it.

- Private communities, under geoism, are glorified land owners. They operate functionally indistinguishable from a residential landlord/homeowner. The only difference would be scale.

- This means such communities are obligated to return the land value their community resides on to everyone outside the community.

- This would seem an insurmountable task given the size of private communities, but it is made easier if the residents of the communities themselves are ultimately paying LVT for each subsection they reside on.

- This means the private community organizer is off the hook for the majority of the land value.

- In fact, they might ultimately get paid if their jurisdiction over said community makes living in that community more valuable than otherwise. This is the Henry George Theorem in action.

- Knowledge that all other entities in a community are obliged to follow a minimal set of rules (other rules might be built on top of these selectively) and that one would receive certain community services from the private community organizer might make the community a profitable enterprise.

- It is also easier to resolve the problem of rent because one doesn’t need to track down the source of rent, only its existence and magnitude. This problem by itself is problematic enough. Who is obligated to receive rents is another problem I haven’t figured out.

3.3. The supply of land offered for sale in the market often changes, so why is land fixed? -N

Yes, the quantities offered for sale are not fixed, but the total amount of land available is fixed. The sale of land just changes the persons who have title. The total quantity is important in setting the market rent and price of land. There are no competing suppliers for any particular land site. The fixed total quantity, and the fact that land was provided by nature, makes land rent an economic surplus that can be tapped with no economic damage.

3.4. Could rents get passed onto the tenants? -N

No. There is a consensus among economists that Land Value Tax cannot be passed onto the tenants.

The basic gist is that tenants can go to another location with a lower location value. This property owner here is being charged less in taxes because the location value is lower. That would just mean they pass on slightly less expenses to their tenants, right? It would, except the tenants can keep going to locations with lower and lower location value until they reach the location with zero location value. The land here is essentially worthless. They would prefer to live closer to the city but their expenses for living here, further out, and the expenses they would incur for living closer in the form of higher rent are identical. The landlord must provide superior service rather than charging more for increase in location value.

Site rent cannot be passed onto the tenant because the landlord is already charging the market price. Additionally, it cannot be passed on because there is now an increased supply of rental properties on the market. Tenants can now threaten to move if the landlord attempts to pass it on.

When rent is collected on unimproved values, land will become much more readily and cheaply available. Many more people will have access to sites and be in a position to build their own houses and create or operate businesses. All you’d need to borrow, if at all, would be equal to about 10% of the current unimproved site value; enough to cover the first year’s site rent. Compare this to the gigantic burden of current mortgages at inflated interest rates.

Many existing tenants would move and take up sites elsewhere. The law of supply and demand will reverse the current situation by forcing landlords to compete to attract tenants by: improving terms and conditions, carrying out building and internal improvements, undertaking promotional activities in commercial centres, etc. In other words they would have to start renting buildings alone and forego the unearned income from the site itself.

In such a market, if your landlord tried to increase the rent, you would simply move. You could confidently threaten your landlord that if he didn’t lift his game, you would move out. In such a climate, landlords will be improving their buildings in an effort to attract clients. It will be a buyer’s market.

Landlords, especially smaller landlords, would ultimately benefit from Community Site Rent in any case, in that, although they would be foregoing the site rent as part of their income, they would be in the same position as other citizens in that the benefits from a move to Community Site Rent would offset and probably outweigh their initial loss. Larger landlords, the greater part of whose incomes currently derive from ground rents alone, would probably be more likely to lose overall, and may well take their capital offshore. The community would probably gain from such an outcome. Readership of online independent media would surge during such a period of transition!

3.5. How would Georgism make housing more affordable?

Georgism would tax land values to incentivize landlords to build more housing.

3.6. How is the supply of housing related to the supply of land?

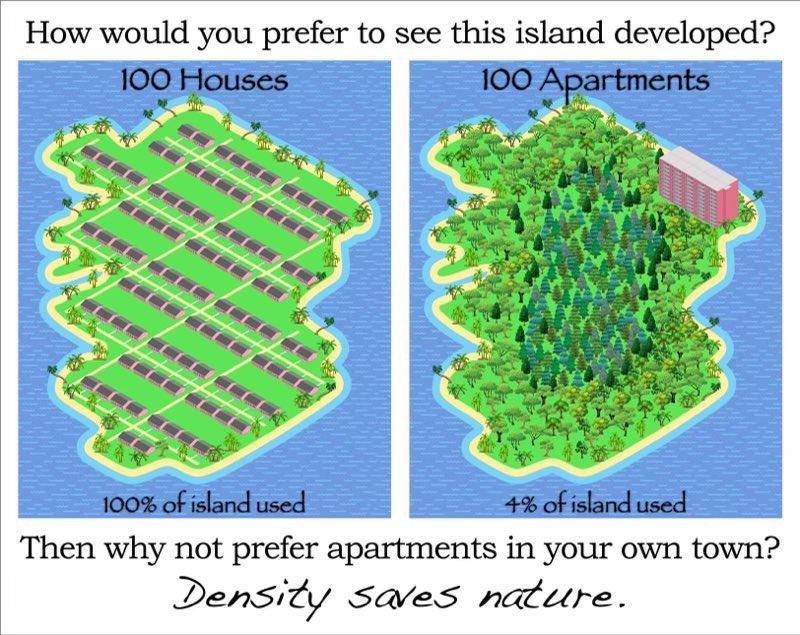

The supply of land is fixed. Nobody can create more land. The supply of housing is closely connected to the supply of land. Unfortunately, the supply of housing is kept artificially scarce, due to awful urban development and property taxes. Property taxes penalize landlords for building more housing. It’s thus not economical for landlords to build more housing, so the supply of housing is fixed.

3.7. Land Values and Land Prices

3.7.1. What is the difference between Land Value and Land Price? -N

Land Price is the accumulated capitalisation of economic rent. It’s what the market pays in a marketplace where land speculation is encouraged and title is bought in a one-off transaction (as per at auction). Land value is the actual rental value of a site ie what can be physically earnt from that location.

McDonald’s is the world’s 2nd largest landowner. They are renowned for ‘doing the sums’ before committing to a future store and buying a piece of land. They hire statisticians to count the number of cars that pass by the location. Using their statistical models, they calculate for example, that if 10,000 cars pass each day with a likelihood of 200 potential customers spending $8 each, the site is worth $11,648,000 ($1600 x 7 days x 52 weeks x 20 years). They will refuse to pay above that market price because they know they can’t earn enough to pay the mortgage. Under our system, they would refuse to pay more than $582,400 (1600 x 7 x 52 weeks) for a yearly site rental because they know the actual Land Value. To pay anything above this is uneconomical as they wont be able to earn the extra revenue to cover this. A similar situation is the astute small business investor who sits in for a month on a prospective business , recording all transactions (in say a Milk Bar) to see how much the business is actually worth, before committing to the asking price. Often under our present system, speculation forces Land Prices above what can realistically be earned by its occupants. Under a Site Rental system, when there are 70,000 cars passing by and 300 people entering the store, the company will naturally pay more back to the community, keeping in time with the growth of society. In time Land Price should equal zero, but Site Rental will replace that, growing as society does, ensuring the people get a share of the improvements.

3.7.2. What would happen to Land Prices?

The speculative component of land prices would be removed as the increased supply of property (huge tracts are withheld from supply by speculators) leads prospective buyers to pay only what the property is worth in terms of location, infrastructure and amenities.

It’s probable that land prices would drop to zero within the first couple of years. Remember, there is a big difference between land price and land value.On the introduction of the system, anyone holding land speculatively would either have to put it to productive use or get rid of it. If they hung onto it, they would be out of pocket by the annual rental value. Putting it to productive use would result in a dramatic increase in demand for labor and therefore an increase in trade and thus in the general welfare. Getting rid of it would result in the asking price for land dropping substantially to the point where supply exceeded demand, with the seller getting progressively more desperate to sell and thus avoid the site rent.

In the end, land price is replaced by land value, as represented by the Site Rental. The Site Rental is representative of only what can be earned by occupying that piece of the planet.

3.7.3. Wouldn’t the land value tax (LVT) increase the price of land?

No, because it wouldn’t change the supply or the demand for land.

Most people who ask this question mistakenly think that the LVT would be paid on top of the price of buying land. But this is inaccurate because land would not be bought at all under Georgism, as land could only rented by paying the LVT (the price of the land rent).

Since the land rent is the only cost to being able to possess/occupy land, since LVT would effectively be the price of land, and since the price of land would only be dependent on the supply and demand of land, LVT would not increase the price of land.

3.8. But isn’t land speculation the same as any other commodity speculation?

[I haven’t finished writing this section yet. It takes time to write stuff.]

3.9. Why is only land speculation bad? Why not also SBF-style speculation?

Every form of rent-seeking is undesirable for an economy and that there should be laws to prevent it whenever it occurs. We oppose Sam Bankman-Fried style speculation, but it’s harder to make a case that that counts as rent-seeking. SBF-style speculation is more akin to gambling instead of investing since the speculators don’t really own any true wealth and the risks are much higher. Gambling in small amounts won’t hurt an economy, but it becomes a problem when it’s done on the scale of the FTX scandal and a feedback loop is created.

If the stock market counted as rent, then that would effectively mean that there is no value in researching to distinguish between profitable investments and non-profitable investments. To an extent, the same could be said for land speculation, but the key difference between speculating on land versus speculating on a stock is that the former deprives everyone else of a natural resource in fixed supply, whereas the latter does not.

One of the problems with making a law against SBF-style speculation is that it can difficult to define and differentiate. It may just be better to let gamblers suffer the consequences of their actions. I oppose capital gains tax because stocks represents real wealth, are actual investments in a company, and actually have positive benefits on the economy.

3.10. How can you predict that Georgism would increase economic growth?

One of the reasons why economics is so unpredictable is because economists have been assuming for centuries that social mobility is mostly dependent on environmental factors, when it’s actually dependent on genetics. The mathematical optimization behind Georgism is very sound. Another thing is that virtually all tax proposals have largely failed to benefit society in the past because they don’t aim to reduce rent-seeking, they punish productivity in one form or another. Neither applies to LVT.

But it’s based on assumptions that space is effectively utilized. Is that mere speculation?

There are many examples in that section. Just imagine how slow and inefficient your computer would run if it used a finder’s keepers approach to memory and CPU power. That’s the system that we have now (a finder’s keeper’s approach to land ownership).

I’m arguing for a system that allocates resources in the most efficient manner possible, similarly to how modern OSs are designed.

But a society is not based on processors and chips, it’s based on the unpredictability of humanity?

There’s a lot of complexity and unpredictability in ranking processes too. There are entire CS courses that teach memory, CPU, and resource management, like Theory of Computation.

Yes, but then the code isn’t even finished itself, so how would it be able to be successfully applied to humanity when it in itself isn’t completed in it’s own area? That would be very speculative?

Georgism works because it uses free market principles. We can’t know how valuable land is we don’t put a price on its monthly value. The same cannot be said of the current system, where land values are not appraised on a regular basis, since people can own land for years and decades, no matter how inefficiently they may be using it.

I think this is missing a perspective that the free market itself is what determines value, not some kind of appraisal system, and it seems unfair to say that a free market is good for everything but land.

That’s not true for natural resources.

3.11. How would Georgism resist government corruption?

[I haven’t finished writing this section yet. It takes time to write stuff.]

3.12. What other effects could Georgism have on the economy?

Georgism would increase fertility rates since it increases the society’s wealth.

[I haven’t finished writing this section yet. It takes time to write stuff.]

3.13. Why is income from land ‘unearned’ income? -N

Some say it’s an investment, and the investors deserve a return, just like someone who has bought shares or has money in the bank. A return of a certain percentage from investments in productive activities is fine. After all the investor has provided risk capital to some enterprise which is going to produce some product for public consumption, and the returns to the investor simply reflect the level of risk and an inflation factor. We have no problems with that. But if you buy a site this year, be it in the CBD or the outer suburbs, and hang on to it for ten years waiting for community funded infrastructure and pressure of artificially created land shortage, or rezoning to push up the price, then such profits as may arise in excess of those due to inflation, belong to the community. How could anyone dispute this?

3.14. There is no such thing as a free lunch. -N

The costs of Community Site Rent would be carried by every home owner, everyone who rents, and everyone who consumes goods or services which have land as an input. There shouldn’t be such a thing as a free lunch, but there certainly is. The wealth which is generated by the very presence of the community, and which ends up in private hands pays for many a free lunch, in fact many a free banquet with all the trimmings and has done for hundreds of years. These people would be the big losers, in that whatever part of their income derived from the community-created or common wealth would be absent from their incomes. This is not to say that J.Packer and his mob may still not generate a very respectable income from the legitimate employment of their undoubted directorial and entrepreneurial skills. All they would be foregoing would be their former share of the earnings of their fellow human beings. All of those among the wealthy elites in this lovely country of ours and elsewhere, whose incomes exceed their earnings are in effect stealing the bread from the tables of the millions whose earnings vastly exceed their income.

3.15. But there is n/ unimproved land value. The only income generated from land is from the application of labor and capital to the land. -N

No, there is an unimproved value. It is the value put on land by the community before its even touched by the hand of man or woman. It’s the amount you would pay for virgin farmland, or an empty city site. It is this value, the unimproved value, which is the common wealth and which belongs to all in the community. Your improvements on the other hand belong to you. Every single drop of sweat, or byte of brain power you apply to the increase in value of the asset, be it a new building, a hotel, or a thousand hectares of wheat should be yours. Not the government’s. You make it, you keep it. But return the community created rent to the community.

3.16. Politically, is Georgism more of a left-wing or a right-wing ideology?

Part of the beauty of Georgism is that it can be compatible with nearly every political ideology there is. Georgism promotes equal land rights and free markets, both of which are common liberal values. There are geo-socialists, geo-conservatives, geolibertarians, and geo-anarchists. There is also no reason why Georgism can’t be compatible with a Christian/Muslim Theocracy, Monarchy, Communism, or even Fascism.

Some people have argued that the Georgist values in equal rights and more equitable land/wealth distributions makes Georgism more of a left-of-center ideology, but there’s no reason to categorize Georgism as being “inherently leftist”. Historically, all the earliest proponents for land value taxation were classical liberal economists and political philosophers. Today, those historical figures would be better categorized as Libertarians, not Leftists. Karl Marx was a very harsh critic of Henry George, and many leftists are also in favor of income taxes and/or sales taxes because they don’t believe that land value taxes would be enough to achieve wealth equality. So, it doesn’t follow that Georgism is an inherently leftist position, although you could argue that it does a better job at achieving leftist values than most leftists’ political proposals. If anything, it makes more sense to simply describe that Georgism is a liberal value. There are many different types of liberals who support Georgism, and it certainly wouldn’t be accurate to group them all together as “leftist”.

Georgism also has good synergy with many religious worldviews. Many Christians and Muslims believe that God created the Earth to be shared by all humans equally, so there are strong religious arguments for Georgism.

Fascists tend to favor mixed economies that aren’t perfectly “capitalist” or perfectly “socialist”. In a sense, a Georgist economy would already be a mixed economy that fits this description. So, Georgism could be compatible with Fascism too.

Georgism is compatible with a monarchy too. Under a Georgist monarchy, all land would be considered public property (nominally, the property of the King), while it is rented to private individuals.

In my personal experience, Alloidal Libertarians and Anarcho-Capitalists tend to be the most die-hard anti-Georgists out there. Ancaps are opposed to all taxes of every kind, and they even go as far as to pejoratively label Georgists as “Land Communists”. Ancaps very strongly value private property and private ownership. Nevertheless, there are some Ancaps who accept Georgism, but they’re usually gate-kept from being labeled as Ancaps and usually prefer to call themselves geo-anarchists to differentiate themselves. ZC’s Case Against Libertarianism page also has many great arguments as to why True Libertarians ought to be Georgist.

Above all however, I personally argue that Georgism should be characterized as a Pragmatopian and Neo-Malthusian position. Georgism and Neo-Malthusianism both aim to conserve natural resources that exist in fixed supply. Most Georgists tend to be Cornucopians since Henry George was a harsh critic of Malthusianism, but I’ve written extensively about Neo-Malthusianism and Georgism should work harmoniously together, rather than antagonistically. Georgism will eventually fail without some form of population control, so Pragmatopians are arguably the most Georgist of them all since we are the only ones who advocate for a sustainable Georgist political system that’s guaranteed to potentially last for centuries.

4. Switching to Georgism

4.1. Overview

Any conversion over to a Georgist taxation system would have to be a very gradual process, taking at least 30 years in order to give everybody enough time to re-adjust their personal finances, especially for the people who are relying on land speculation as part of their retirement portfolio. But that’s really the only drawback to Georgism. Once you’re through that, it’s smooth cruising from there on out.

The way how I was willing to switch from Qwerty to Colemak, in spite of the 1-month transition period, is analogous to how I support Georgism, which would also require a transition period. Both provide better long-term results because they are both applications of the Space Utility Optimization Principle.

Additionally, in order for Land Value Tax to be truly effective, it must be widespread, otherwise those not having to pay a land value tax will have an even bigger advantage. This is just like how states without income tax have an advantage in labor costs over states that do have income taxes, or how states without sales taxes have an advantage in sales over states that do have sales taxes. Likewise, if a Georgist government imposes taxes on negative externalities, like pollution, there would need to be a tariff on goods from countries which didn’t impose such a tax. Otherwise you would just be subsidizing pollution elsewhere.

It is already common practice in the real estate industry to separately evaluate of land values from property values. The easiest way to transition to Georgism would be to gradually transition the Property Taxes so that they tax the unimproved value of the land instead of the improved value of the land, in increasingly greater proportions over time. Property Taxes are basically a combination of a good tax (land) with a bad tax (property), so you slowly reduce the bad tax proportion to nothing while increasing the good tax proportion (LVT) to higher amounts. And then from there, you slowly reduce sales taxes, income taxes, and so forth to 0%, while slowly increasing the LVT to 100%. We already have all the machinery for implementing Georgism, it’s just a matter of gaining enough political support for starting the decades-long transitioning phase by educating more people about economics.

4.2. How would such a system be implemented? -N

In short, the same way it is now. Critics of the LVT are fond of pretending that land values are not already being taxed, when in fact they are (albeit to a limited extent) by existing property taxes. The machinery for the LVT is already in place. Thus, all that is necessary to implement the LVT locally is to exempt houses, buildings and other improvements from taxation, and thereby focus existing property taxes on land values only. In this way the property tax would be converted to a land value tax. As for state and federal taxation, geolibertarians advocate a bottom-up system whereby a portion of the LVT-revenue generated locally is sent to the applicable state governments, and a portion of that, in turn, to the federal government. Ideally, this would be phased in over a period of years. That is, as the LVT is slightly increased each year, taxes on wages, sales and capital goods would be slightly decreased. This process would continue until all taxation is eliminated save for a single tax on land values.

Whether a political party were elected on a site rent platform, or a government were persuaded to change over in mid term as the result of a referendum, then there would obviously need to be a period of transition in which legal matters were sorted out, legislative changes made, procedures established etc.. This could possibly take a year or so. At the point where the system becomes law, then the current unimproved site values at that time (as is already available for scrutiny wherever rates are collected) would be used as the basis on which the first annual rental is struck at a rate of say 10%, or whatever was determined as required for government expenditure (using the same methodology to set rates).

Although initially set at ten percent on the unimproved value of all sites, the asking price for land would obviously fall dramatically on the introduction of the site rent system, and would drop in many areas to zero as the supply of sites outstripped demand. Site Rental, representing Land Value, replaces the inflated Land Price that is possible at present with wasteful land usage. At this point, within a year or so of the implementation of the scheme, the government would simply collect the annual site rent as its sole source of revenue. In other words, the occupier would enjoy exclusive use of the site for as long as they continue to reimburse the community for the benefits which their exclusive access gives them. In that way, the value created by the community’s presence – the economic rent – is returned to the community as revenue for its government.

There would no doubt be a bit of panic, especially among all those whose whole or partial income derives from rent in one form or another, but even these people would see, once they’d calmed down, that the benefits to the whole economy of such a radical change would massively outweigh any losses. Those whose income though is largely gained from community generated rent through monopolistic holdings of land and resources, licenses, etc. would be violently opposed, obviously, as their livelihood would be threatened and they would be reduced to relying on their own skill and efforts to produce income. They would be forced to live on their earnings and not their incomes.

On the positive side for these people would be the fact that they would still retain their mansions and their yachts; the legitimate part of their income from shares in productive enterprises like BHP, CRA etc., would still be coming in – in fact it may increase, as these enterprises would be taking part in a massive resurgence of industrial and corporate activity fueled by higher wages in the pockets of the consumers and cheaper manufacturing costs for the exporters. So even they would not necessarily be any worse off in the end, and would enjoy living in a happier, less fear-ridden and corrupt society. The best salve to their fears would be to give them all a years supply of valium, and a government-subsidised short course along the lines of “Only work generates wealth”.

Regarding the immediate redundancy of the very large numbers of taxation and related department functionaries, including Ministers and Ministerial departments ; even if the government undertook to continue employing them to twiddle their thumbs rather than paying out large packages, I think most of these people, within months of the start of the new system would be eager to get into it, seeing that they could employ their talents in a totally free market and generate as much wealth as they wanted to.

4.3. More Details About The Implementation, Logistics, And Consequences Of Georgism

Draft Georgist taxation plan with as many details as possible regarding:

- Describe the implementation of Georgism in as much detail as possible.

- Give more specific details regarding the implementation of taxation rates across different types of land and varying land values.

- How would the mathematics (and machine learning?) of the mass appraisal be calculated?

- Note that the calculation and appraisal of land values is just as valid as the definitions of all the other general variables in this list.

- How much taxes would be collected, and how often?

- How would the various land value taxes be adjusted for inflation?

- Who would get taxed when the ownership title isn’t very clear?

- What would be the detailed route of procedure if someone does not pay their LVT?

- When land is available for people to settle it, would they be signing a contract with the government to pay the designated LVT rates?

- If someone does not pay their LVT to the point where they forfeit their occupation of the land, do they lose the improvements on the land, do they get compensated for losing those improvements, and/or does the value of those improvements get used to help pay the LVT that they failed to pay?

- When land is available for people to settle it, would someone have to buy the improvements on the land as well?

- What are the most realistic reactions to the gradual implementation of Georgism?

- What are the most realistic reactions to the Georgist taxation system itself?

- How would the logistics of the collection of other economic rents (besides real estate values) work?

- How would pollution be measured before collecting pollution taxes? would it be possible to measure all types of pollution?

- How would prices be effected regarding: food grown on farms, labor, etc?

- Can it be verified that rents cannot get passed onto the tenants, when taking into account the effects of capital markets?

- Although this page claims to prove that LVT cannot get passed onto the tenants, it’s actually not very helpful because it doesn’t cover the effects of capital markets at all, and the empirical study discussed in the article was on tax rates too low to cause an exodus of capital from real estate. As far as I know, nobody has taken this into account when arguing that LVT cannot be passed onto the tenants.

5. Wealth Distribution, Ownership, And Equality Questions

5.1. How does Georgism achieve “equal ownership of land”?

All land rents are used to pay for government revenues. Most Georgists propose a Citizen’s Dividend (nowadays known as UBI) if there’s a surplus in government revenue, but there are other alternatives to this.

5.2. Would the government be the de facto of all the Earth’s land? -N

[I haven’t finished writing this section yet. It takes time to write stuff.]

In a sense, yes. However, eeeeeeeeeee.

No, because government would have no authority to dictate when, how, or by whom land itself is used; it would only have the authority to ensure the rent of land goes to everyone on an equal basis, since all individuals have an equal right to the use of land. Henry George put it thusly:

“We do not propose to assert equal rights to land by keeping land common, letting any one use any part of it at any time. We do not propose the task, impossible in the present day of society, of dividing land in equal shares; still less the yet more impossible task of keeping it so divided.

“We propose–leaving land in the private possession of individuals, with full liberty on their part to give, sell or bequeath it–simply to levy on it for public uses a tax that shall equal the annual value of the land itself, irrespective of the use made of it or the improvements on it….We would accompany this tax on land values with the repeal of all taxes now levied on the products and processes of industry–which taxes, since they take from the earnings of labor, we hold to be infringements of the right of property.” [Emphasis mine] – The Condition of Labor, p. 8

The only alternative to George’s proposal is to treat land as the unconditional property of a relative few. The problem with this alternative is that, when taken to its logical conclusion, we find that the fruits of individual labor must inevitably be treated as conditional property for everyone else. Why? Because no one can produce wealth in the first place unless he or she first has access to land. Consequently, since all land is legally occupied, and since producing more land isn’t an option, those who don’t have titles to land cannot legally access the earth – and thus cannot legally sustain their own lives – unless they first “consent” to pay a portion of their earnings to those who do have titles to land. (This is why geolibertarians regard landed property as the mother of all entitlements.)

Land itself does not originate from labor; thus, property in land does not originate from labor, but from the law that confers ownership to an individual or group. Landed property is therefore law-made property, and is, in that sense, clearly distinct from man-made property. Thus, to compel one group to pay rent to another group for mere access to the earth is to elevate law-made property above man-made property. And since the latter is an extension of self-ownership, to elevate the former above the latter is to strike a blow at the very foundation of property rights.

“Disregard of the equal right to land necessarily involves violations of the unequal right to wealth.” – Max Hirsch, Democracy vs. Socialism, p. 372

To this some might object that the LVT does just that – compels one group to pay rent to another group for mere access to the earth. While this objection may sound logical at first, it is fatally flawed. Why? Because it ignores a universal law of today’s economy: the fact that land rent gets paid either way – regardless of whether or not it gets diverted into the public treasury.

Thus, it is not a question of if land rent gets paid, but to whom and on what basis.

If it is paid exclusively to titleholders on the basis of the earth being the unconditional property of titleholders, then, for reasons given above, the property that non-titleholders have in themselves and in the fruits of their labor is thereby violated. If, on the other hand, it is paid to the community on the basis of the individual members of that community each having an equal right to land, then said property right (the right to one’s self and the fruit of one’s labor) is thereby upheld foreveryone – both titleholder and non-titleholder alike.

Another common objection is that, if government collects the rent of land, it automatically becomes the owner of land. This objection is based on the myth that the terms “rent collector” and “owner” are synonymous. While many rent collectors do, indeed, own the property on which they collect rent, there are, nevertheless, thousands of private rental agents and property managers all over the country who routinely collect rent on properties they do not own. Thus, one does not have to be an “owner” to be a “rent collector.” Government is no exception to this rule.

That doesn’t mean the government of, say, North Korea does not assert ownership over the land on which it collects rent. It does. But it is not merely the authority to collect land rent, but the authority to dictate how land is used, that makes the North Korean government an “owner” of land. Critics of the LVT repeatedly insist that you can’t have one authority without the other, but as mentioned above, the rent-collection services provided by non-owning rental agents and property managers prove just the opposite.

This becomes easier to understand once you realize that “property” refers, not to a single right, but to a bundle of rights – the right to rental income being one of them. The other rights include the right to possess, use, exclude, and transfer title. As any lawyer will tell you, those rights can be transferred in whole or in part.

“The concept of a bundle of rights comes from old English law. In the middle ages, a seller transferred property by giving the purchaser a handful of earth or a bundle of bound sticks from a tree on the property. The purchaser, who accepted the bundle, then owned the tree from which the sticks came and the land to which the tree was attached. Because the rights of ownership (like the sticks) can be separated and individually transferred, the sticks became symbolic of those rights.” [Emphasis mine] – Fillmore W. Galaty, Wellington J. Allaway, & Robert C. Kyle, Modern Real Estate Practice, 14th ed., p. 16

This is precisely why, in the U.S., it is possible for city councilmen to collect a portion of land rent through property tax levies, yet be lawfully excluded from the land itself by whoever holds title to that land. Although the local government in this case has a legal right to a certain percentage of the land’s rental value, the titleholder has all the other rights of the aforementioned “bundle.”

Not only would the titleholder retain those rights under a geolibertarian system, those rights would be strengthened by the fact that (1) he would no longer be taxed for being productive, thus making it far easier for him to afford whatever the rental charge is, and (2) the law would require any surplus revenue to be distributed equally as a citizens dividend. (The latter would provide a built-in incentive for citizens to bring enormous pressure to bear on government to limit its spending, since less wasteful spending would mean a greater surplus, and thus a higher dividend.)

5.3. What is the difference between ownership and possession?

[I haven’t finished writing this section yet. It takes time to write stuff.]

For now, see: But private land ownership is necessary to resolve tragedies of the commons.

5.4. What do Georgists think about the Labor Theory of Value (LTV)?

The Labor Theory of Value is circular and vacuous. If it was just “The value of X is the amount of labor necessary to produce X”, then it would just be stupid, but not circular. But the LTV is defined as “the value of X is the amount of socially necessary/useful labor required to produce X”, and “socially necessary/useful” presupposes value.

A better alternative to the Labor Theory of Value is Marginalism. u/green_meklar has written some great essays on the problems with the LTV, and why Marginalism is a better economic theory.

5.5. What do Georgists think about equality?

One of the goals of Georgism is to reduce wealth equality, not to eliminate it. If we made everyone 100% equal in wealth, then other inequalities would matter more anyway, e.g. genetic inequality, sexual inequality, moral inequality, etc, so it’s futile to make absolute wealth equality an imperative.

We believe in equal opportunity, not equality of outcomes. The latter would reduce the production of wealth, make everyone worse off, and cause tyranny. Many people compare Georgism to Communism, but they are very different:

- Georgism is motivated by a positive vision for the future, whereas Communism and Socialism are motivated by hatred of those who are wealthy and successful, and they fantasize about killing billionaires, landowners, and/or politicians.

- Georgism makes a distinction between ownership and possession. Georgists are okay with the wealthy and the elite maintaining possession over their land (and ownership over the fruits of their labor), as long as they compensate everyone else for being able to have that right. By comparison, Communists and Socialists want to steal property from the wealthy and redistribute it for everyone else to own.

- Georgism is supported by solid classical economics. Communism and Socialism are not.

- Georgism has never been tried before. Communism and Socialism have been tried, and they failed.

- Georgism doesn’t enable rent-seeking, nor does it cause free-rider problems, nor does it penalize people for being productive. Communism and Socialism do all of these.

- Georgism would reduce corruption, compared to alternative proposals for bootstrapping market prices. If anything, implicit ad hoc pricing creates even more opportunities for corruption and evasion, in comparison to taxing natural resources at the point of extraction.

I think it’s theoretically possible for Georgism to be enforced by non-elites if the power structure is just right after great reform or a major revolution, but I also wouldn’t be surprised at all if the world’s natural resources ended up being controlled by the elites, since that’s pretty much the same outcome of every ideology (that the elites take over everything). Even if Georgism resulted in the elites seizing power to manage the pricing of land and natural resources (and thus the distribution to some extent), I would still view it as preferable. Even the elites have an interest in conserving natural resources for a sustainable future, which natural resource taxation would achieve, along with all the other benefits on this list.

5.6. What do Georgists think about landlords?

[I haven’t finished writing this section yet. It takes time to write stuff.]

5.7. How would Georgism reduce wealth inequality?

When everybody owns land equally, this ensures that everybody has equal access to the three factors of production: Land, Labor, and Capital. It follows that economic productivity is increased, and wealth inequality is dramatically reduced. The massive wealth inequality that exists today is in large part caused by the skewed and unequal ownership of highly valuable land.

Since the wealthiest people are naturally the ones who own the most land and the most valuable land, Land Value Tax would therefore reduce economic inequality, because the LVT would mostly fall on the wealthiest members of society.

Additionally, Georgism would make housing more affordable. When housing is unaffordable, it tends to affect the lower classes more than the upper classes, so that’s another way how Georgism will reduce wealth inequality.

As a thought experiment for illustrating how land is the ultimate driver of economic inequality, imagine if there were no scarcity of land. Imagine so much high-quality, easily accessible land that anyone can use as much as they want without reducing the amount available for others to use. How many of the ’problems of capitalism’ would still remain in such a world?

5.8. Wouldn’t the wealthy simply find some way of evading land value taxes? -N

You can’t move a nation’s natural resources off shore. You can’t evade a Resource Rentals charge, just as you can’t evade paying your rates or mortgage, whether you’re Joe Bloh or James Packer. In our current system if you don’t pay your rates or your mortgage your site is reclaimed by the owner or by the local authority. That wouldn’t, and shouldn’t change. If you want to own shares or property overseas that should be no skin off anyone’s nose, good luck to you. If you’re using wealth generated in this country to do it, that’s fine too because you would also be spending some of the profits here anyway.

5.9. Wouldn’t the wealthy sell up and flee with their wealth? -N

Few would flee; they would stick around and utilise their wealth in productive enterprises which would allow them to utilise their managerial or entrepreneurial skills to generate more wealth for themselves and, through resource rentals, for the community at large. People could shift cash, gold jewelry, antiques, paintings or any other moveable assets offshore to their heart’s content. They could use all the modern electronic means at their disposal to move funds, and do whatever they like with their money. Anyone who’s willing to work for a living rather than be supported by the labor of others will be grateful. If there is a flight of non-productive capital, the only function of which was to hold land and resources out of use in expectation of some future unearned profit, then their departure would not be missed in the long run. As these non-producers fought to get rid of their unused sites, the prices would drop, and Mr. and Mrs. Joe Bloh would be able to realise the dream of owning their own house. Joe and his partner might also be able to start up a little business and produce for themselves a passably good life. In fact the whole population would have a much better chance of enjoying the fruits of their own labor.

5.10. Wouldn’t LVT discourage people from owning land?

LVT does discourage people from owning land. That’s a feature, not a bug. It ensures that people only use as much land as is efficient for them, leaving the rest for someone else to use. That’s what we want, as opposed to the land-hoarding and rentseeking behavior that dominates our current real estate market. (Actually, we want to raise the tax so high that the sale price of the land becomes zero, erasing the notion of privately ’owning’ land at all. Everyone would be a tenant on common land, paying back everyone else for the land they use and, conversely, getting paid for all the land they don’t use.)

5.11. Wouldn’t the LVT make it more difficult to own land, especially for poor people? -N

No, because land rent, as mentioned before, gets paid either way – regardless of whether or not it gets diverted into the public treasury.

Even when you pay the sale price of land, you are paying land rent, since the sale price is simply the rental value divided by the interest rate. And since land is in fixed supply, decreases in land value taxation are invariably capitalized by titleholders into higher rents and land prices. Thus, people in general, and the working poor in particular, end up paying back in higher rents and land prices what they presumably get from the tax cut; and pay back even more in terms of (1) a lower margin of production (and thus lower pre-tax wages), and (2) a heavier reliance on wage and sales taxes.

So once again, it is not a question of if land rent gets paid, but to whom and on what basis – to a fraction of the population, on the basis of the earth being “owned” by a relative few; or to everyone equally, on the basis of the earth being that to which all have an equal right of access? Geolibertarians believe it should be the latter, since that is the only just and practical way of establishing true equality of opportunity without enforcing equality of outcome in the process.

As for poor people, the LVT would actually make it much easier for them to acquire land, since it would reduce the artificially high price of land, as well as increase wages by raising the margin of production, on the one hand, and reducing the need for wage taxes, on the other.

5.12. Why would anyone want to own land under this system? -N

At present, wages gain about 3% p.a, the sharemarket 7-10% and now land, instead of the 15% plus gains of recent (on a huge lump sum amount), would be left with about 10% of a much smaller increased land value ie a 10% share of whatever gain on a $45,000 Site Rental versus the old 15% on $450,000. Owning land would thus still see competitive returns to what can be earnt in banks or the sharemarket, just not as large a capital gain as the lump sum would be greatly reduced in size and growth. For more see Land Price versus Land Value.If the person is a renovator, they are entitled to all of the gains from the improved building.

Also, with the speculative component removed, the land market would be less volatile, reducing the risk of land ownership. Cheaper land values would give our youth hope.

5.13. How would homeowners pay land value tax, if their land value rises while wages don’t? -N

If the majority of land rents were collected by the community, the land market would become much less volatile. Speculative booms and crashes in land values would be greatly dampened, if not completely eliminated. During a transition period, in which land values were becoming a greater share of public revenue, there would be an opportunity for companies to provide insurance against an unexpected increase in the land value tax. The insurance would have a cost at the time of purchase, so that the new titleholder would know if he could afford the payments. Also, retired folks with low incomes could postpone the payments until the property is sold or inherited.

5.14. A rich man has a large mansion; a poor widow has a small house on an adjoining lot with the same value. Is it right that they both pay the same tax? -N

There is no reason in justice why the community should not charge poor widows as much for monopolizing valuable land as it charges rich men. In either case it is a special privilege which should be paid for. In our sympathy for the rare widower in this situation, let us not forget the hosts of working people who not only do not live next to mansions but have no place to live but by some landlord’s consent. They would find it much easier to get a place to live under the Single Tax than now.

6. How Georgism Would Affect Different Interest Groups -N

6.1. How would Georgism affect wages?

[I haven’t finished writing this section yet. It takes time to write stuff.]

6.2. Wouldn’t taxing land at 100% of its value be unfair to landowners?

It would be if 100% LVT started getting applied overnight, but only because many people’s wealth and life savings are stored in the value of their land, especially for many middle-class homeowners.

Any conversion over to a Georgist taxation system would have to be a very gradual process, taking at least 30 years in order to give everybody enough time to re-adjust their personal finances, especially for the people who are relying on land speculation as part of their retirement portfolio. But once society is through that, the economy will be better off than it was before the transition and it will be smooth cruising from there on out.

For as labor cannot produce without the use of land, the denial of the equal right to the use of land is necessarily the denial of the right of labor to its own produce. – Henry George, Progress and Poverty, Book VII, Chapter I

6.3. If someone buys land in good faith, under the laws by which we live, would that person not be entitled to compensation for individual loss if we taxed away the value of his land? -N

Even at present, if a landowner does not pay taxes, his or her land is confiscated by the government without compensation. Land grants and taxation are clearly matters of the general public policy; they are legislative and not contractual in character. Titles to land values and privileges of exemption from taxation are voidable at the pleasure of the people. The reserved right of the people to terminate grants of land value is a part of every grant of land.

Since Progress and Poverty was written, there has been a considerable body of public opinion in favor of land value taxation, and the proposal has been put into application in several parts of the world. Notice, therefore, has been served that there is an effort in progress to accomplish community collection of rent by proper methods. As this movement grows, people cannot be allowed to make bets that it will fail and then, when they lose their bets, to call upon the government to compensate them for their loss. Note too that land titles will remain. The land will be just as good as before — even better — for building or producing.

6.4. Wouldn’t Georgism give landowners more influence over the government since they would be paying all the taxes?

It’s not clear why non-taxpayers wouldn’t have a voice. They would probably have just as much representation as they do now under this current system, and even if that’s not very much, there are ways to improve the structure of the government so that it listens to all its citizens, but that is very complicated and a discussion for another thread.

Keep in mind that we are also in favor of head taxes since we believe that everybody who benefits from government services should be required to make a contribution for receiving them. Head taxes don’t reduce economic productivity since they are a flat rate that is applied to every citizen.

6.5. How would Georgism curb unemployment? -N

Under this proposed reform, land and resources would no longer be kidnapped and held out of productive use by private monopolies. Access would be within the reach of anyone who was willing to reimburse the community for the community-created value of the site. Wage levels, uninhibited by fear of unemployment, would flourish as demand for labor surged. People given a free hand to produce and to prosper, and knowing that they would get as much income as they wanted to work for – or as little as they needed to comfortably survive – would begin to do the sorts of work that pleased them. The quality and range of goods and services would increase dramatically, thereby improving their attractiveness to our trading partners.

6.6. Wouldn’t land value tax hurt farmers? -N

Nope. Georgism would help everybody, including farmers.

Land Value Tax is not the same thing as Land Area Tax. Rural land tends to be worth far less per unit area than urban land, so it’s not as big of a deal as you might think. For instance, in the United States, urban land constitutes less than 3% of the total land area but over 70% of the total rent (and thus potential LVT revenue). So farm land could only account for less than 30% of the total, which is a very small portion of the land rent, especially in proportion to its size. If anything, farmers might receive more money via the Citizen’s Dividend than whatever that they might pay in LVT.

For another thing, LVT would: 1. densify suburbs that sprawl into farmland, and 2. tax land speculators. Both of these factors would only make rural land cheaper for farmers.

No, it would help farmers. In the first place, the LVT would fall primarily on urban land, not rural land, since land values are concentrated primarily in urban areas. In the second place, the increased cost of paying a higher tax on land value would be more than offset by (1) the savings incurred from paying lower taxes on everything else, (2) the reversal of urban sprawl (and thus of the inflationary pressure that sprawl currently imposes on the value of farmland), and (3) the increase in income that would result from both a higher margin of production and a surge in overall economic activity. For supportive empirical evidence, see the following:

The critical point is that the Site Rent is levied on unimproved (no structures, fences or other improvements) values. In marginal country this would be very little indeed. In high rainfall fertile country it would be more since the unimproved land itself is more productive. However, it would still be minuscule compared to current mortgage levels. It is ultimately the market which decides the value anyway. Once you’ve paid the site rental, you keep what your earn, and pay no tax, direct or indirect, hidden or not, on anything else. You keep the fruits of your labor, and you earn more or less as much or as little as your desires demand. Productive farms pay less under a proper Site Rental system than under CIV (Capital Improved Value), as they generally have developed their farms with more buildings and machinery. Farmers lobbying for CIV have generally been hoodwinked by the real estate lobby, who prefer CIV as then households and business subsidise vacant lots.

6.7. How will Georgism affect multinationals (MNC’s)? -N

If Community Site Rent were introduced, then, wages would rise, and the following would result:

MNC’s and large businesses typically rely on large sites with big carparks. As large land users they will have to pay higher site rents than your average small hardware store, helping to restore the balance, moving us towards re-localisation.

Consumers, having more disposable income, would not be forced any longer to opt for the cheapest product, and would be in a position to take ethical decisions on what they do and do not buy.

The result of this would be that any MNC’s which were using unethical practices would lose sales against more ethical competitors

If MNC’s had production sites in this country they would have to offer higher wages to hold their workforce, which they could may struggle to do whilst remaining competitive. This may lead them to close down operations here and move the production offshore to a cheaper labor source.

If the MNC derived a significant part of their income from ground rents, either directly or indirectly, (i.e. through cheaper labor or raw materials), then they would probably be forced to cease operations in this country anyway if they wished to maintain the same levels of profitability for their international shareholders.

6.8. How will Georgism affect lenders and borrowers? -N

The vast bulk of unproductive sites, including those held for speculative gain or in anticipation of upzoning, would come onto the market. Unimproved land values therefore would initially fall which would in turn make them more accessible to all, whether first home buyers or commercial enterprises. The site rent, being based initially on a percentage value therefore would probably produce less revenue from existing occupied or utilised sites, but since there would be a large increase in the number of utilised sites, the total revenue would remain or more likely increase.

The cost of mortgages would drop because the land component would cost less – and in a very short space of time, it’s sale price would drop to zero and all you would be paying would be its annual rental value. In this scenario, you would only be borrowing to the value of a year’s site rent at the most for the land component, after which time you would more than likely earned enough to easily afford the next years rental. You would still be paying off the money borrowed on the building. As well as this, because everyone would retain a much larger portion of their earnings, they will be able to come up with a larger deposit, and also to pay off any loan much more rapidly. The demand for money will drop, resulting in interest rate falls.

6.9. How will Georgism effect new and long-term mortgagors/owners? -N

Those who have, not long prior to the changeover, taken on a mortgage over a residential or commercial property may feel ill-served by such a site rent for revenue system as they will be obliged to pay both the mortgage repayments, and at the same time be liable for the community site rent. They are no worse off though and in fact are probably better off, because;

Employment conditions & wages will greatly improve due to the increase in small business. Other spin offs include a safer society, better public transport and reduced overall household debt pressures. The long-standing mortgage payer has been liable for a comparatively similar amount, but over a longer period, but will never the less still be liable for the same site rent. For the newer mortgagor, in all likelihood interest rates in the new system would decline dramatically, due to both a decline in site values and therefore demand for finance, making the mortgage effectively cheaper. On top of this, both the above mortgagees will from the date of changeover be able to retain a much larger portion of their income, since all taxes will have been abolished.

6.10. How will Georgism meet the needs/demands of Entrepreneurs and Manufacturers? -N

Opportunities would abound. Large corporations which now rely on making maximum profit from cheap, shonky and second rate goods would face serious competition from smaller operators with lower overheads (due to site rents), so would have to improve their game or disappear. People would have much more money to spend, and would therefore create many more new markets for the enterprising entrepreneur. It should be remembered that if, prior to the change, the entrepreneur was getting the bulk of their income from productive work, not from site rents, then they would be bound to gain from the proposed change. Those with capital already at their disposal could if they wished put it to use establishing new enterprises or improving existing ones, and so benefit from the new system which allows them to retain a much larger portion of the wealth they generate, while at the same time returning to the community its rightful share of the community generated site value.

6.11. How will Georgism meet the needs/demands of Exporters and Importers? -N

All tariffs and duties would disappear. Local product would be cheaper to produce, of better quality, broader ranging, and more abundant than ever before. Our products would fetch a premium on the world markets. Imports would be cheaper. We could economically import the very best capital equipment and use it to produce even better products for home consumption and re-export. Consumers would have ready access to the best the world had to offer in the way of manufactured goods and other products

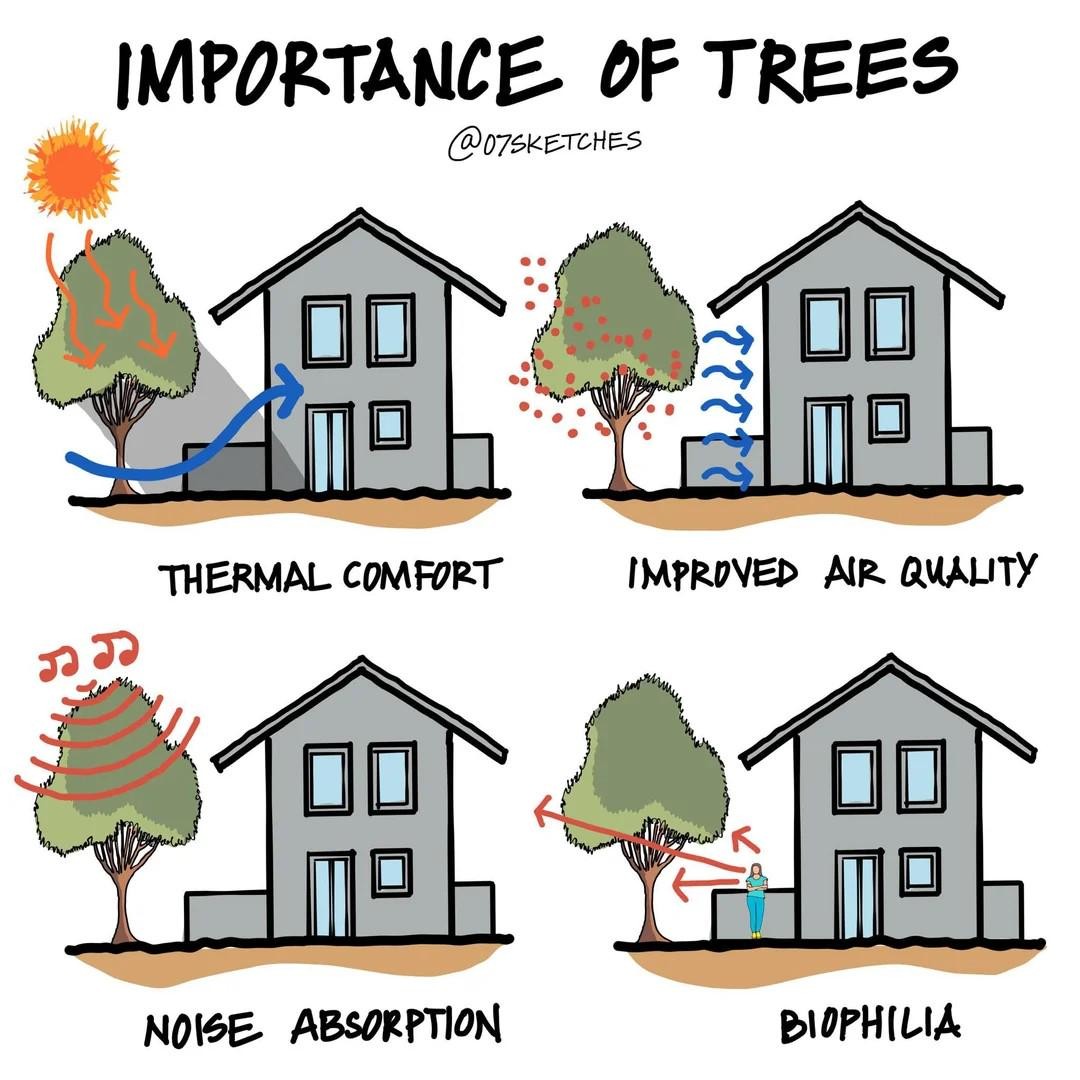

6.12. How will Georgism meet the needs/demands of Environmentalists? -N

Pollution, toxic wastes, erosion, salination, land degradation, over extraction, decimation of tropical forests, diminishing fish stocks, threatened wild life; Private monopolisation of land and resources is the direct cause of all these environmental problems. Leases and royalties charged to the extractive industries do not reflect the true value of the minerals and other resources extracted. The true cost of these items must include the cost of ensuring the absolute control and minimisation of any resultant environmental degradation. If this resulted in the prices of some of these resources increasing, then that is what we must be prepared to pay. In the manufacturing industries it is cut-throat competition among producers which leads to much of the current pollution and environmental degradation, and tempts those involved to cheat and to side-step regulations etc. in order to survive. With a site rent for revenue system they could afford to comply with the strictest environmental controls.

6.13. Who wins; who loses? -N

Broadly, anyone who gains part of their income from site rent will lose that part of their income through the Community Site Rent . Whatever part of their income derives from their own earnings will not be taxed any longer and will remain entirely in their hands. They will keep what they earn and no more.

The biggest losers therefore will be those who rely entirely for their income from site rents, and who do not earn their living by contributing to the production of wealth. The further down the scale one goes in the ratio of income from site rents compared to that from productive work, the better off the individual will be. At the very lowest end of this scale, where the individuals income is made up entirely of what they earn, then the maximum benefits of the system will apply. In other words the people at the bottom lose least, those at the top lose most. You could not have a more progressive revenue system than that! Thus we have a total inversion of the age old pattern of the community’s wealth aggregating towards the top at the expense of all at the bottom.

It should be remembered that those with large fortunes at the time of changeover would not necessarily be disadvantaged. Certainly they would lose whatever part of their incomes which were derived from the monopolising of community resources, but they would still retain all their existing capital, which they would be free to invest in productive, wealth-generating enterprises, and could utilise their managerial and entrepreneurial skills. They would not lose their yachts, island hide-aways, mansions and penthouses, rural acres. Nor would they need their battalions of accountants and tax minimisation experts.

6.14. But people can also lose value from owning land. Land speculation is like investing. -N

That’s often true during recessions. But what the land speculator loses, the community does not gain. What the land speculator gains, however, the community does lose. As between land speculation and the community, losses cannot be justly charged against gains. The taxation of land values, incidentally, will put an end to these “unearned losses” as well as to unearned gains.

6.15. Won’t it fall harder on the prince in his mansion than on the pauper in his hovel? -N

Don’t forget that the proposed Community Site Rent is struck initially on unimproved values. So the value of the building, be it hovel or mansion, is irrelevant. But to answer the point regarding equity;

- The owner of a site of unimproved value $1m will pay $100,000 nominal site rent in the first year, and in subsequent years whatever the annual assessed rental value is – in fact probably around 10% of the site’s notional capital value, even though “capital value” or “price” will no longer exist.

- The owner of a farm, whose 2000 hectares, excluding any improvements is worth $100,000 will pay $10,000 nominal site rent in the first year, and in subsequent years whatever the annual assessed rental value is. This farmer will pay no tax on his income from the crops, no tax on the farm machinery, new car, furniture, fencing materials, food, clothes, beer, books, new computer, TV set, home entertainment centre, RM Williams boots.

- The owner/occupant of the fibro hovel would be unlikely to be living next door to the mansion, and more likely be in an outer suburb sitting on land worth maybe $40,000 at current values. He/she will pay $4000 nominal site rent in the first year, and in subsequent years whatever the annual assessed rental value is.

- But what would all these people be paying now in direct and indirect tax? The millionaire; probably 5 or 10% of his/her true income in income tax, but the same indirect taxes as everyone else. The average wage or salary earner, between 30 and 50% of their income on income tax and then the same as the millionaire in indirect taxes on everything else. A minimum of 50% of average incomes disappear in direct and indirect taxes, an increasing proportion of which goes to support an ever more unwieldy and expensive administration. You don’t start earning a clear wage until more than half way through the year.

6.16. How would old age pensioners on valuable sites pay their site rents? -N

Pensioners would be better off, but will be faced with some difficult questions in the beginning. At present day inflated land prices, the $330,000 house would see the unimproved price at $230,000. Ten percent of this is $23,000 in site rental. This would be a shock to most retirees. However, it must be remembered that we are presently at record highs for housing, and a site rental would return property prices back to more realistic levels within a few years. Thus in a year’s time 30% of the speculative price has probably been brought out of the price. Site rent then falls to $14,000. It should fall back again to about $10,000. It is likely that a sole pensioner on $15,000 will initially not be able to cover their site rental. They should sell and move to a smaller premises. Alternatively, they could do a reverse mortgage and pay their site rental from their estate. That is a negative but look at the positives:

- their grandkids can now afford a house, reducing future generation’s reliance on any inheritance

- they can walk the streets in comfort as crime drops due to increasing small business, employment opportunities and wages.

- their pension’s purchasing power will be much higher, giving them more dignity, as the removal of direct and indirect taxes will boost pensions by 40%. These are just some of the gains, making this small sacrifice well worth any short term transitional issues.

A couple on a pension will be able to continue as per normal, though they may have to tighten their belts for the first year. The added purchasing power of 40% will more than make up for the short term pain of the transition.

Since governments would be in surplus they would happily, with no pressure from the community, increase pensions to a level which provided a comfortable retirement to those who had through their working life contributed by their very presence to the wealth of the nation.

It’s worth bearing in mind that this reform is not simply another slightly more novel form of tax. This proposed Community Site Rent recaptures and returns to the community at large what was previously being diverted into private hands. It allows what was previously paid out, with considerable pain, through a complex and massively inefficient array of taxes to remain in the hands of the people who produced it. For this reason alone, and for the justice of the principle on which it stands, the Community Site Rent demands serious consideration.

It the worst came to the worst, and the occupier was too ill or incapable, then the site rent debt could simply be deferred until the death of the occupier, and then retrieved from the estate, as are mortgagee debts and rate arrears now.

After spending a lifetime seeing some people work blood, sweat and tears for little return and others greasing the system through property speculation, many retirees would be able to look back in satisfaction as being the ones who made a small sacrifice for the greater good.

6.17. What happens to the self-funded or partly self-funded retiree? -N

These deserving retirees would be overjoyed with such a scheme. Although they would indeed have to continue repaying the community for the value which the existence of the community itself gives to the site, this would be truly small beer compared to what they’re currently being stung. When you consider that on top of their income and capital gains taxes, they are paying up to 32% of every dollar on a truly biblical multitude of taxes including income tax for the producers and providers of goods and services plus all the other indirect and hidden taxes we all endure.

If the unimproved value of the site that these retirees occupied was worth say $100,000 (excluding the value of the house), then they would be paying a maximum $10,000 nominal site rent in the first year, and in subsequent years whatever the annual assessed rental value is. The buying power of what’s left grows by at least a third since they’re paying no income tax or capital gains tax, nor are they paying any of the other multitude of hidden taxes and imposts. They’d be rapt.

6.18. Will pensioners and retirees – currently untaxed but living in their own property, be liable for site rents as well? Will they be reimbursed for past taxes paid? -N