Georgism And Population Control

Why They Both Imply Each Other

1. Introduction To Population Dynamics

No matter how much people may want to deny it (Georgists included), Overpopulation is a serious concern for humanity. If we don’t regulate our population by ourselves soon, then the world population will exceed its carrying capacity, and humans will be doomed to die by famine, war, and disease, just as they have for most of human history. It won’t have to be this way though, if the world can amass enough political support for population control.

Our Overpopulation FAQs explains in comprehensive detail what overpopulation is, how/when it happens, why the world is destined to become overpopulated under its current management, the devastating consequences that will happen if the Earth faces overpopulation, and the fairest, most reasonable solution that we can implement to prevent that from happening.

Our Eugenics & Reproduction Licenses FAQs page offers an introduction to what eugenics is, explains its misconceptions, explains why it will be necessary to preserve modern civilization, and makes a proposal for how we should implement it in the fairest, most efficient, and most reasonable way possible via reproduction licenses.

The next section of this post debunks the fallacious Cornucopian arguments made in Chapters 6 through 9 of Progress and Poverty by Henry George. Many Georgists perceive Georgism and population control as being antagonistic to one another because they think that the latter is unnecessary if we have the former. As we shall show, that is wishful thinking. Instead of counteracting each other, Georgism and population control should both be seen as complimentary with each other’s effects. The last sections explain why Georgism and population control both imply each other. Georgist reasoning can be extended to solve the most dire crisis currently facing humanity.

2. Debunking Chapters 6 through 9 of Henry George’s Progress and Poverty

In the refutation, I am going to be quoting the modernized version of Progress and Poverty, edited and abridged by Bob Drake. This version of P&P is shorter and written in a form of English that’s easier for modern-day English speakers to understand. Hence, the text may not be exactly what Henry George wrote word for word. However, everything quoted here still shares the same semantics and ideas as what he believed in. And that is what counts. Regardless, the original, unabridged version of Progress and Poverty is also available for free for those who want to see it.

2.1. Refuting Chapter 6: ’The Theory of Population According to Malthus’

Malthus unashamedly makes vice and suffering the necessary result of natural instinct and affection. Despite being silly and offensive, as well as repugnant to our sense of a harmonious nature, it has withstood the refutations and denunciations, the sarcasm, ridicule, and sentiment directed against it. It demands recognition even from those who do not believe it. Today it stands as an accepted truth (though I will show it is false).

Humans don’t have a “harmonious nature”. To the contrary, humans have been killing each other and fighting wars for all of human history. The late 1900 and early 2000s are exceptional since they have featured very low amounts of war compared to earlier history, but they won’t last unless we can solve the problems of modernity. It’s not “silly” or “offensive” to acknowledge this at all. It’s just reality. And if we want to avoid it in the future, then we need to understand how human nature actually works. When Henry George spreads lies and fallacious reasoning about human nature to the minds of millions of people, he is undermining humanity’s potential to attain a prosperous future.

To a factory worker, the obvious cause of low wages and lack of work appears to be too much competition. And in the squalid ghettos, what seems clearer than that there are too many people? We may also note that, in our present state of society, most workers appear to depend upon a separate class of capitalists for employment. Under these conditions, we may pardon the masses – who rarely bother to separate the real from the apparent.

Cornucopians may want to deny it, but it’s true that increasing the supply of labor leads to lower wages. This is perfectly consistent with the laws of supply and demand. It also explains why the Deep State Establishment has deliberately increased the amount of immigration to Western countries like Canada, Australia, etc in the early 2000s, even though it causes so many social problems.

It’s also true that Georgism would cause wages to rise (by increasing economic efficiency). Georgism would also increase production of wealth and the Earth’s carrying capacity, so we can predict that this would cause fertility levels as well. So, unless there is population control to prevent the supply of labor from increasing, the wage increases that Georgism would cause would only be temporary. Population control will be necessary to prevent the consequences of the Iron Law of Wages.

But the real reason for the triumph of [Malthus’s] theory is that it does not threaten any vested right or antagonize any powerful interest. Malthus was eminently reassuring to the classes who wield the power of wealth and, thus, largely dominate thought. The French Revolution had aroused intense fear. At a time when old supports were falling away, his theory came to the rescue. It saved the special privileges by which only a few monopolize so much of this world.

It may be true to some extent that Malthus’s theory was partially responsible for distracting the public from the importance of land economics, at the time that Henry George published Progress and Poverty in 1879. However, most people reject Malthus’s theory today in the 2000s. Instead, there are other reasons why Georgism failed to become more popular during the 1900s. And Malthusian theory definitely wasn’t one of them.

See: Why Georgism Lost Its Popularity: The Successive Mistakes of the 1900s.

It proclaimed a natural cause for want and misery. Malthus’ purpose was to justify existing inequality by shifting the responsibility from human institutions to the laws of the Creator. For if those things were attributed to political institutions, they would condemn every government. Instead, he provided a philosophy to shield the rich from the unpleasant image of the poor; to shelter selfishness from question by interposing an inevitable necessity. Poverty, want, and starvation are not the result of greed or social maladjustment, it said. They are the inevitable result of universal laws, as certain as gravity. Even if the rich were to divide their wealth among the poor, nothing would be gained. Population would increase until it again pressed the limits of subsistence. Any equality that might result would be only common misery.

These are some pretty strong and dubious claims. As far as I know, Thomas Malthus never created his theory of population dynamics with the intent to benefit the rich at the expense of the poor. It’s more likely that he was trying to write an empirical and well-reasoned description of how the human population works (at the time). Everything that Malthus wrote in An Essay on the Principle of Population was correct up to the year that it was published in 1798.

Free speech is important to a functional and prosperous society, and it should be protected. The other reason why Malthus wrote his response essay was because he wanted to express his disagreements, predictions, and response to two works made by the following authors:

- Sketch for a Historical Picture of the Progress of the Human Mind by French philosopher and mathematician Marquis de Condorcet.

- Enquiry Concerning Political Justice by English philosopher William Godwin.

Moreover, the essay had strong impacts on the future. It raised discussion and awareness about population dynamics, which contributed to passing the Census Act 1800, which required Great Britain to take the first Census of England, Scotland and Wales in history. Censuses collect important information and have great historical value. The essay also influenced Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace when they conceived of the theory of evolution. Henry George is foolish to portray Malthus’s essay as negatively affecting mankind.

Of course, Malthus obviously didn’t make correct predictions for the 1800s or the 1900s. But if it’s fair to harshly criticize Thomas Malthus for being unable to accurately predict the future, then it ought to be fair to harshly criticize Henry George if the human population exceeds the carrying capacity, in spite of all attempts to increase the carrying capacity. As we shall see, Henry George doesn’t understand how population dynamics work at all. His theory has no predictive power, so it’s bound to make the wrong predictions for the future.

See: Has Malthusianism been debunked?

… Recently, this theory has received new support from Darwin’s Theory on the Origin of Species. Malthusian theory seems but the application to human society of “survival of the fittest.” Only “the struggle for existence,” cruel and remorseless, has differentiated humans from monkeys, and made our century succeed the stone age.

Social Darwinism is Nature. Malthusianism received support from Darwin’s Theory on the Origin of Species because Malthusianism is largely coherent with Darwinism and vice versa when the carrying capacity of an environment fails to increase.

It’s also not really accurate to describe evolution as the “survival of the fittest”:

Evolution is not really the survival of the fittest. It is the reproduction of the fittest. Survival is just a means to reproduction. Fitness is the ability to reproduce. Selection operates through both death and birth. For most species, premature death is the main form of selection. Competition for mates can also be important, especially for males. For modern humans, selection operates mainly through fertility. Genes that correlate with high fertility are positively selected. Genes that correlate with low fertility are negatively selected.

– Blithering Genius, “We Cannot Transcend Evolution”

Read More: Understanding Biological Realism and Evolution.

2.2. Refuting Chapter 7: ’Malthus vs. Facts’ Part I: Fallacious Arguments

The variety and inaccuracy of arguments that George makes in this chapter are best characterized as gish gallop.

Reproduction under such conditions is at a high rate, which, if it were to go unchecked, might eventually exceed subsistence. But it is not legitimate to infer that reproduction would continue at the same rate under conditions where population was sufficiently dense and wealth was distributed evenly. These conditions would lift the whole community above a mere struggle for existence.

Correct. When wealth increases, so does the population.

Once the population reaches the carrying capacity once more, there are fewer natural resources per capita. If the increased population doesn’t produce enough wealth to compensate for the dawn of its existence, then wealth per capita will also decline.

Nor can one assume that such a community is impossible because population growth would cause poverty. This is obviously circular reasoning, as it assumes the very point at issue. To prove that overpopulation causes poverty, one would need to show that there are no other causes that could account for it. With the present state of government, this is clearly impossible.

We agree that we need to isolate all the possible factors we can evaluate the causes of poverty.

Malthus begins with the assumption that population increases in a geometrical ratio, while subsistence can increase in an arithmetical ratio at best.

That’s not an assumption, when we include the historical context. It’s a historical fact that subsistence only ever increased arithmetically at the time when Malthus wrote his Essay on the Principle of Population, before the Industrial Revolution happened. Whenever subsistence rose, so did the carrying capacity, and so did the population. The reason why the world population is not geometrically larger compared to its previous sizes is because populations cannot exceed their carrying capacities. Carrying capacities have only been able to increase arithmetically historically, hence why most population increases prior to the Industrial Revolution had only increased arithmetically.

The main body of the book is actually a refutation of the very theory it advances. His review of what he calls positive checks simply shows that the effects he attributes to overpopulation actually arise from other causes. He cites cases from around the world where vice and misery restrain population by limiting marriages or shortening life span. Not in a single case, however, can this be traced to an actual increase in the number of mouths over the power of the accompanying hands to feed them. In every case, vice and misery spring either from ignorance and greed, or from bad government, unjust laws, or war.

Humans are selfish and greedy by nature, whether they admit it or not. That is a reality that we have to live with. It’s an inescapable part of the human condition.

Once humans are the apex predator and they have reached the carrying capacity of their environment, the majority of deaths will be from warfare, unless there is a very high rate of disease. People who let their children die of starvation rather than going to war, will be eliminated by those who fight for their children’s survival.

Nor has what Malthus failed to show been shown by anyone since. We may search the globe and sift through history in vain for any instance of a considerable country in which poverty and want can be fairly attributed to the pressure of an increasing population. Whatever dangers may be possible in human increase, they have never yet appeared. While this time may come, it never yet has afflicted mankind.

This is completely false. Earlier in this chapter, George argued that we cannot assume that overpopulation causes poverty if there’s other factors to be considered. And now he’s arguing that whenever overpopulation accompanies poverty, we should assume that the poverty is caused by mismanaging of natural resources instead of overpopulation, even though it’s not possible to separate the two factors. This is intellectually dishonest.

In the interest of an honest scientific analysis into the causes of poverty, I reiterate that we need to isolate all the possible factors before we can evaluate the causes of poverty, including overpopulation and mismanagement of natural resources. If we cannot isolate all the factors, then we need to use sound reasoning to determine what causes the disasters and correlations. The historical facts, evolutionary reasoning, and deduction presented in the essay conclude that overpopulation can (but not necessarily) cause poverty.

Historically, population has declined as often as increased. It has ebbed and flowed, while its centers have changed. Regions once holding great populations are now deserted, and their cultivated fields turned to jungle.

Where are Henry George’s sources and evidence for this claim??[1] Populations have declined before, but it’s not true at all that they “ebbed and flowed”. When we look at a graph of the world’s population history, we don’t see a population that waves up and down. What we see is that it remained at a nearly constant level for most of human history (the carrying capacity), and that it gradually increased whenever new technology and new food sources were acquired. When populations did go down, it was because some combination of war, disease, and famine reduced the population (e.g. the Mongol invasions in Eurasia, the black plague in Europe, Old World diseases in the Americas, etc), because how else would a population decline when it’s otherwise well-adapted to its environment enough to populate it up to its carrying capacity? In fact, warfare was the primary factor for limiting Amerindian populations before Europeans colonized the Americas.

New nations have arisen and others declined. Sparse regions have become populous and dense ones receded. But as far back as we can go, without merely guessing, there is nothing to show continuous increase. We are apt to lose sight of this fact as we count our increasing millions. As yet, the principle of population has not been strong enough to fully settle the world. Whether the aggregate population of the earth in 1879 is greater than at any previous time, we can only guess. Compared with its capacities to support human life, the earth as a whole is still sparsely populated.

The world population has always increased whenever the carrying capacity has increased.

And just because the Earth can be been considered fairly underpopulated in 1879, that doesn’t mean that the current Earth (in 2024) can’t still face an overpopulation crisis in the next few decades.

Another broad, general fact is obvious. Malthus asserts that the natural tendency of population to outrun subsistence is a universal law. If so, it should be as obvious as any other natural law, and as universally recognized. Why, then, do we find no injunction to limit population among the codes of the Jews, Egyptians, Hindus, or Chinese? Nor among any people who have had dense populations?

Because enough people died off each generation to prevent this from being necessary, whether that was from disease, famine, war, etc, or some combination of those factors. As recently as the 1800s, 75% of children died before the age of 5 years old. By contrast, the modern world doesn’t have the same high rates of infant mortality that had historically kept the human population in check.

It’s really surprising that Henry George wasn’t able to figure this out, especially when he grew up in the 1800s. Surely he would’ve been able to recognize that diseases killed a lot of people during his lifetime, and realize that they were even deadlier before technology improved, right? Apparently not. George’s obliviousness to basic facts is a demonstration of how poor his research and critical thinking were.

There are only two ways to regulate populations: 1. high mortality rate, or 2. low and/or sustainable birth rate (which may be accomplished via population control). Mass death is highly undesirable (hence why humanity eliminated it), and low fertility cannot be voluntarily achieved on a societal level, so that leaves population control as the most desirable and only feasible option for regulating populations in the modern era. If we don’t regulate our population with population control, then billions of people will be destined to die in one way or another.

This quote also ignores historical populations that faced overpopulation because they failed to regulate their reproduction. Easter Island is such an example. The American Indians are another example.

On the contrary, the wisdom of the ages and the religions of the world have always instilled the very opposite idea: “Be fruitful and multiply.”

Yes, exactly. The memetic systems that promote the highest levels of reproductive success are the ones that dominate the world. That’s how evolution works.

If you think about it, religions that instill “Be fruitful and multiply” are going to be more popular and have more followers than religions that don’t encourage reproduction. Memes that don’t encourage reproduction are known as fashions or cults because they discourage reproduction and don’t get passed down to future generations. In the long term, fashions don’t dominate the world, traditions do.

Generally speaking, religions don’t make people do things. People make people do things. People conform to those around them. Religion is used to rationalize implicit norms, and to prevent thought. That’s fine when people have a functional culture, but not when thought and change are necessary.

If the tendency to reproduce is as strong as Malthus supposes, then how is it that family lines so often become extinct? This occurs even in families where want is unknown. In an aristocracy such as England, hereditary titles and possession offer every advantage. Yet the House of Lords is kept up over the centuries only by the creation of new titles.

Many biological species and their families have gone extinct too in the past. There are millions of examples of this happening throughout the Earth’s history, and acknowledging this fact does not contradict anything in our theory of biology, evolution, and population dynamics. Just because some family lines go extinct, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t other family lines that are reproducing with high fertility. Family lines that go extinct will always be replaced with family lines with higher fertility that don’t go extinct, just as they always have. To a great extent, Nature has to be that way in order for evolution to occur in the first place.

As for George’s claim regarding the House of Lords, it’s irrelevant to this discussion, but I could investigate it further if someone can find a source and information for looking into the specifics on that claim.

To find the single example of a family that has survived any great lapse of time, we must go to immutable China. There, descendants of Confucius still enjoy peculiar privileges and consideration. Taking the presumption that population tends to double every twenty-five years, his lineage after 2,150 years should include 859,559,193,106,709,670,198,710,528 souls. Yet, instead of any such unimaginable number, his descendants number about 22,000 total. This is quite a discrepancy!

That calculation assumes an infinite carrying capacity, which China obviously doesn’t have. A population cannot exceed beyond its carrying capacity, and given that dozens of generations have inhabited the Earth since Confucius’s time and that people die over the years, there is no discrepancy here.

Further, an increase of descendants does not mean an increase of population. This would only happen if all the breeding were in the same family. Mr. and Mrs. Smith have a son and a daughter, who each marry someone else’s child. Each has two children. Thus, Mr. and Mrs. Smith have four grandchildren. Yet each generation is no larger than the other. While there are now four grandchildren, each child would have four grandparents.

This assumes that the average life expectancy of the population is fixed, so it ignores how an increasing life expectancy would increase the population by making it take longer for the older generations to die. It also assumes that every person is going to have exactly two kids. Needless to say, first assumption (fixed life expectancy) obviously isn’t true in the modern world since life expectancy is increasing. The second assumption isn’t going to be true in the future either, since overpopulation is a free-rider problem.

Comparing total population with total area, India and China are far from being the most densely populated countries of the world. The population densities [in 1873] of India and China were 132 and 119 per square mile, respectively. Compare this to England (442), Belgium (441), Italy (234), and Japan (233). The total population of the world was estimated to be just under 1.4 billion, for an average of 26.64 per square mile.

Total land area doesn’t measure carrying capacity, so this quote is misleading and irrelevant.

Since Chapter 7 was so long, I decided to create a separate section to address George’s claims and arguments regarding overpopulation in India, China, and Ireland.

2.3. Refuting Chapter 7: ’Malthus vs. Facts’ Part II: India, China, and Ireland

It is clear that this tyranny and insecurity produced the want and starvation of India. Population did not produce want, and want tyranny. As a chaplain with the East India Company in 1796 noted:

“When we reflect upon the great fertility of Hindostan, it is amazing to consider the frequency of famine. It is evidently not owing to any sterility of soil or climate; the evil must be traced to some political cause, and it requires but little penetration to discover it in the avarice and extortion of the various governments. The great spur to industry, that of security, is taken away. Hence no man raises more grain than is barely sufficient for himself, and the first unfavorable season produces a famine.”

The good Reverend then goes on to describe the misery of the peasant in gloomy detail. The continuous violence produced a state under which “neither commerce nor the arts could prosper, nor agriculture assume the appearance of a system.” This merciless rapacity would have produced want and famine even if the population were but one to a square mile and the land a Garden of Eden.

British rule replaced this with a power even worse. “They had been accustomed to live under tyranny, but never tyranny like this,” the British historian Macaulay* explained. “It resembled the government of evil genii, rather than the government of human tyrants.”

An enormous sum was drained away to England every year in various guises. The effect of English law was to put a potent instrument of plunder in the hands of native money lenders. Its rigid rules were mysterious proceedings to the natives. According to Florence Nightingale, the famous humanitarian, terrible famines were caused by taxation, which took the very means of cultivation from farmers. They were reduced to actual slavery as “the consequences of our own [British] laws.” Even in famine-stricken districts, food was exported to pay taxes.

In India now, as in times past, only the most superficial view can attribute starvation and want to the pressure of population on the ability of land to produce subsistence. Vast areas are still uncultivated, vast mineral resources untouched. If the farmers could keep some capital, industry could revive and take on more productive forms, which would undoubtedly support a much greater population. The limit of the soil to furnish subsistence certainly has not been reached.

It is clear that the true cause of poverty in India has been, and continues to be, the greed of man – not the deficiency of nature.

This excerpt is one-sided, oversimplified, dishonest, and loaded with moralist rhetoric. As is the case with all the other paragraphs that are being refuting on this page. George completely dismisses the role of population growth in exacerbating poverty and food insecurity. I shouldn’t have to state the obvious, but rapid population increases can and do strain resources and contribute to poverty and hunger. This is especially true in the absence of commensurate economic development and agricultural productivity gains.

It may be true that some British policies may have contributed some famines in the Indian subcontinent (e.g. exporting food to pay taxes for famine-stricken districts, the Corn Laws). However, most of those taxes were used to administer the colonies. Colonization did not make the Europeans wealthier since almost none of the colonies generated more money than what was invested into managing them. Hence, why the Europeans couldn’t afford to keep their colonies forever. There is also no correlation between how imperial a country was and how wealthy/successful it was compared to non-colonial European powers. Europe colonized the rest of the world for pride more than anything else. See: The Great Illusion by Norman Angell (1910), pages 86-102.

Maybe the Indian farmers could’ve built industrial infrastructure to tap into uncultivated areas, if they were able to keep more capital. But there’s no way to know this for sure since it didn’t happen. Regardless, we can also argue that European colonization provided many advantages to the colonies. See: Was Colonialism Good or Bad? - What If Alt Hist.

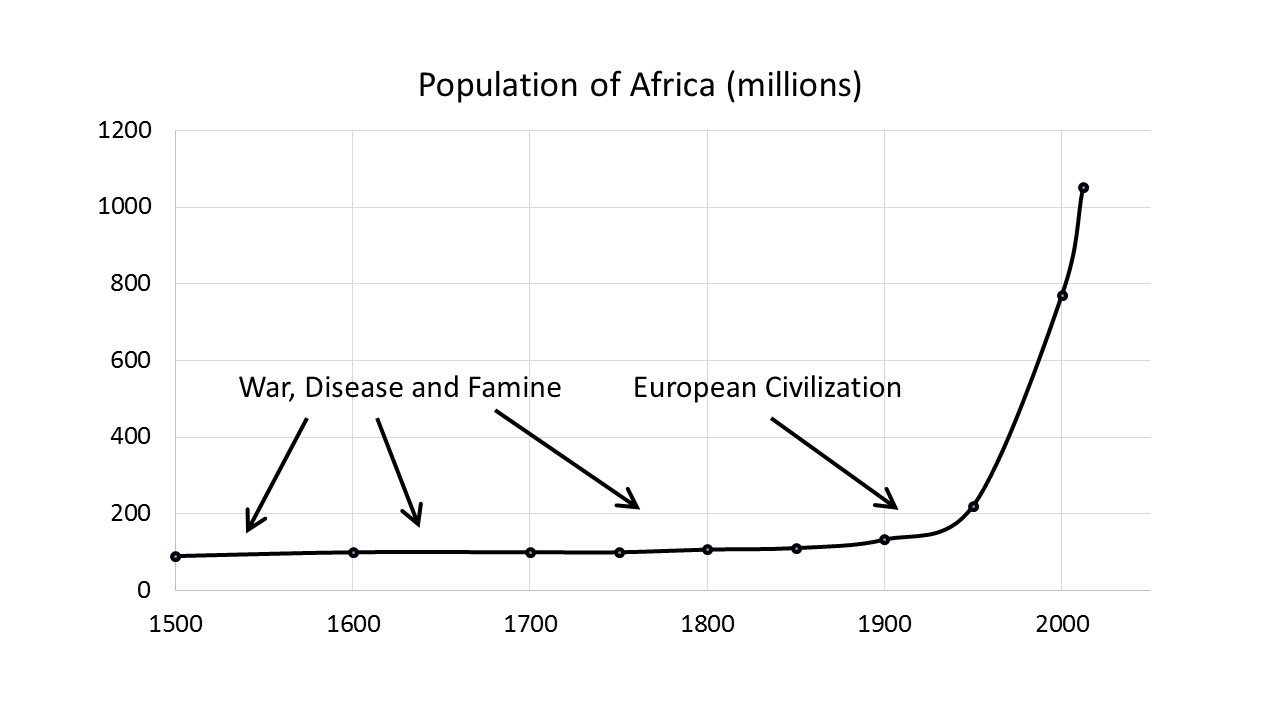

To the contrary, most former European colonies dramatically increased in population during their colonial and post-colonial histories. Before then, their populations were limited by war, disease, and famine. This implies that European colonialism was largely a good thing for most of the world, since European civilization managed to relieve many peoples from the hardships of war, disease, and famine all over the world.

What is true of India is true of China. As densely populated as China is in many parts, the extreme poverty of the lower classes is not caused by overpopulation. Rather, it is caused by factors similar to those at work in India.

Insecurity prevails, production faces great disadvantages, and trade is restricted. Government is a series of extortions. Capital is safe only when someone has been paid off. Goods are transported mainly on men’s shoulders. The Chinese junk must be constructed so it is unusable on the seas. And piracy is such a regular trade that robbers often march in regiments.

Governments do use extortion, but this is necessary to enforce the rule of law and establish free markets.

Under these conditions, poverty would prevail and any crop failure would result in famine, no matter how sparse the population. China is obviously capable of supporting a much greater population. All travelers testify to the great extent of uncultivated land, while immense mineral deposits exist untouched.

China’s population peaked at 1.4 billion people in the early 2020s. The Chinese population could’ve peaked even higher than that if it wasn’t for the One Child Policy, which was enforced from 1979 to 2015. As authoritarian as the One Child Policy may have been, it was enforced for a reason. If the OCP was never enforced, it’s quite possible that China’s population could’ve surpassed the carrying capacity and caused the greatest famine in world history.

Let me be clearly understood. I do not mean only that India or China could maintain a greater population with a more highly developed civilization. Malthusian doctrine does not deny that increased production would permit a greater population to find subsistence.

But the essence of that theory is that whatever the capacity for production, the natural tendency of population is to press beyond it. This produces that degree of vice and misery necessary to prevent further increase. So as productive power increases, population will correspondingly increase. And in a little time, this will produce the same results as before.

I assert that nowhere is there an example that will support this theory. Nowhere can poverty properly be attributed to population pressing against the power to procure subsistence using the then-existing degree of human knowledge. In every case, the vice and misery generally attributed to overpopulation can be traced to warfare, tyranny, and oppression. These are the true causes that deny security, which is essential to production, and prevent knowledge from being properly utilized.

First, George needs to think about this more dynamically. It’s true that having better management of natural resources and more equitable land distribution both could’ve enabled India and China to have more highly developed civilizations. However, that also entails the following:

- They would get richer (more food per capita).

- As a consequence, they would get more numerous. (more people per capita)

- They would get poorer. (less food per capita)

(We’re talking about average Joes, not nobles of course.)

You could have a more efficient system or better agricultural technology, but that is just more surplus for population growth to consume, if the population isn’t held back by disease.

– Paraphrased from Felix, Brittonic Memetics

Second, human nature is violent. Overpopulation tends to famine, which leads to warfare over scarce resources in order to ensure one’s survival. It’d be nice if there was no warfare, tyranny, and oppression amongst humans, but it’s naive to assume that we can eradicate those hardships from humanity. If we want to minimize the number of famines and wars in humanity’s future, then our best hope is to enforce population control.

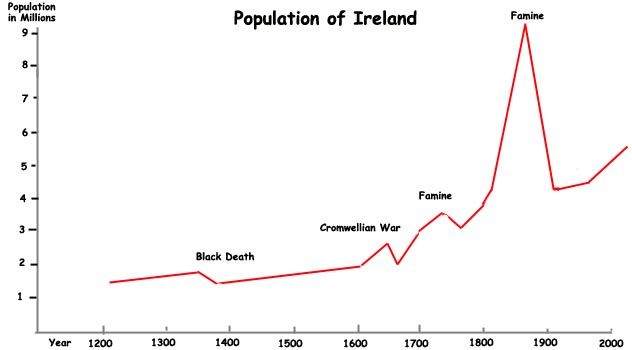

Ireland, of all European countries, furnishes the great stock example of alleged overpopulation. It is constantly referred to as a demonstration of the Malthusian theory worked out under the eyes of the civilized world. Proponents cite the extreme poverty of the peasantry, the low wages, the Irish famine, and Irish emigration. I doubt if we could find a more striking example of how a pre- accepted theory has the power to blind people to the facts.

The truth is obvious. Ireland has never had a population it could not have maintained in ample comfort, given the natural state of the country and the current state of technological development. It is true, a large proportion has barely existed, clothed in rags, with only potatoes for food. When the potato blight came, they died by the thousands.

Did so many live in misery because of the inability of the soil to support them? Is this why they starved on the failure of a single crop?

On the contrary, it was the same remorseless greed that robbed the Indian ryot of the fruits of his labor and left him to starve where nature offered plenty. No merciless banditti plundered the land extorting taxes, as in Asia. But the laborer was stripped just as effectively by a merciless horde of landlords. The soil had been divided among them as their absolute possession, regardless of the rights of those who lived upon it. Most farmers dared not make improvements, even if the exorbitant rents left anything over. For to do so would only have led to a further increase in rent. So labor was inefficient and wasteful. It was applied aimlessly, whereas had there been any security for its fruits, it would have been applied continually.

In the second paragraph, George makes an assumption about the “natural state of the country” of Ireland. The natural state of any country is poverty and inequality. That’s why poverty and inequality have persisted everywhere on Earth for all of human history.

Even after the Great Famine ended, the Land Acts in Ireland and the end of British rule over the Irish Free State failed to end hardship in the Irish countryside. Implementing Georgism would largely bestow economic equality across the island, but as everyone knows, that has failed to happen yet since it’s difficult to solve problems of cooperation, especially ones that would harm the interests of those who have great power.

Even under these conditions, it is a matter of fact that Ireland did support eight million plus. For when her population was at its highest, Ireland was still a food exporting country. Even during the famine, grain, meat, butter, and cheese destined for export were carted past trenches piled with the dead. So far as the people of Ireland were concerned, this food might as well have been burned or never even produced. It went not as an exchange, but as a tribute. The rent of absentee landlords was wrung from the producers by those who in no way contributed to production.

What if this food had been left to those who raised it? What if they were able to keep and use the capital produced by their labor? What if security had stimulated industry and more economical production? There would have been enough to support the largest population Ireland ever had, and in bounteous comfort. The potato blight might have come and gone without depriving even a single human being of a full meal.

It was not the imprudence of Irish peasants, as English economists coldly say, that made the potato the staple of their food. Irish emigrants do not live upon the potato when they can get other things. Certainly in the United States, the prudence of the Irish character to save something for a rainy day is remarkable. The Irish peasants lived on potatoes because rack rents stripped them of everything else. The truth is that the poverty and misery of Ireland have never been fairly attributable to overpopulation.

Writing this chapter, I have been looking over the literature of Irish misery. It is difficult to speak in civil terms about the complacency with which Irish want and suffering is attributed to overpopulation. I know of nothing to make the blood boil more than the grasping, grinding tyranny to which the Irish people have been subjected. It is this, not any inability of the land to support its population, that caused Irish poverty and famine.

I agree that the severity of the Great Famine could’ve been reduced if food wasn’t exported from Ireland during the famine. But I don’t know if the famine could’ve been completely stopped if no food was exported from Ireland at all.

You can argue that it was unfair to concentrate so much land ownership into the hands of the British landlords, but even if the land was distributed more equally, the country still would’ve eventually ran into the same problem as before after a couple decades or so: Ireland had an exponentially increasing population and only a fixed supply of land. Giving them more farmland also could’ve increased the population faster.

Even if British policy was indeed a major cause of the famine, and we grant that better administration could’ve alleviated (or even prevented) the famine from happening, how could we ever be certain that another famine would not have occurred in the future? It’s still both very easy and very dangerous to underestimate the power of exponential growth.

Nevertheless, we should acknowledge that many crop failures occurred in Ireland before the Great Famine Happened. According to Woodham-Smith, “the unreliability of the potato was an accepted fact in Ireland”. Even though the Irish were well aware that they had an unstable food supply and that they had to rent payments to the English landlords in the form of food, the Irish population still continued to grow anyway in the years leading up to the famine. The country didn’t make adequate safeguarding measures to protect itself from a famine either. It’s simply bogus to claim that the rapidly increasing population didn’t contribute to the famine at all. You don’t need to be a genius to realize that fewer people would’ve died if Ireland had a lower population when the Great Famine happened.

It’s also worth quoting Wikipedia:

The growth of population inevitably caused subdivision. The population grew from a level of about 500,000 in 1000 AD to about 2 million by 1700, and 5 million by 1800. On the eve of the Great Famine, the population of Ireland had risen to 8 million, with most people living on ever-smaller farms and depending on the potato as a staple diet.

By the 1840s, many farms had become so small that potatoes were the only food source that could be grown in sufficient quantities to feed a family. This was to have disastrous effects when, in the period 1844-50 a series of potato blights struck, making much of the potatoes grown inedible. This period came to be known as the Great Famine and led to the deaths and emigration of millions of people.

What more could the average Irishman have done? Virtually all Irish people were already farming the most nutrition dense crop (potatoes), maximizing the land usage of their family farms, and making an efficient usage of their labor. There may be things that could’ve happened where the Irish would’ve been better prepared to deal with the famine. But everything that didn’t happen is nothing more than a narrative (about what people wish had happened).

Overpopulation can happen instantly and unpredictably. Every prudent country should be ready for it.

What is true in these three cases will be found true in all cases – if we examine the facts. As far as our knowledge goes, we may safely say there has never been a case in which the pressure of population against subsistence has caused poverty – or even a decrease in the production of food per person.

This rebuttal has proven Henry George’s assertions to be false. He failed to reach our conclusions because he doesn’t understand biology.

2.4. Refuting Chapter 8: ’Malthus vs. Analogies’

There is one additional fact. The actual limit to each species lies in the existence of other species: its rivals, its enemies, or its food.

Humans, however, can extend the conditions that normally limit those species giving our sustenance. (In some cases, our mere appearance will accomplish this.) The reproductive forces of these species then begin to work in service of humans. This increase continues at a pace that our own powers of increase cannot rival. If we shoot hawks, birds will increase; if we trap foxes, rabbits will multiply.

This distinction between humans and all other forms of life destroys the analogy. Of all living things, only humans can manipulate reproductive forces stronger than their own to supply themselves with food. Bird, insect, beast, and fish take only what they find. They increase at the expense of their food. But the increase of humans will increase their food. The population of the United States, once small, is now forty-five million. Yet there is much more food per capita.

It is not the increase of food that has caused the increase of humans – rather, the increase of humans has brought about an increase of food. There is more food simply because there are more people. This is the difference: Both humans and hawks eat chickens – but the more hawks, the fewer chickens; while the more humans, the more chickens.

Humans can are indeed very capable of making more food for themselves in ways that other animals cannot. So far, the industrial ability to produce food has kept up with the developed world’s demand for food. But that doesn’t mean humans are above the laws of physics or economics, or the limits of technology.

Moreover, human subsistence in any particular place is not bound by the physical limit of that place, but of the globe. Fifty square miles, using present agricultural practices, will yield subsistence for only a few thousand people. Yet over three million people reside in London – and their subsistence increases as population increases. So far as the limit of subsistence is concerned, London may grow to a hundred million or five hundred million. For it draws upon the whole globe for subsistence. Its limit is the limit of the globe to furnish food for its inhabitants.

No neo-Malthusian denies that. Regardless, the Earth still has finite resources and a finite carrying capacity that varies with the level of technology. It’s also misleading to only think about one factor that might cause overpopulation, when there’s actually several of them.

For some regions of the world (especially developed countries), it’s inevitable that inescapable mineral realities will eventually limit human populations and/or the standard of living, one way or another.

For other regions of the world, we predict that the world’s supply of freshwater will likely bottleneck the carrying capacity, given current data, historical trends, and sound reasoning. Yes, humans can do things to increase the supply of water, like creating desalination plants or causing artificial precipitation. But it remains to be seen if humanity will have enough water for the coming decades.

But another idea arises that gives Malthus great support: the diminishing productiveness of land. Beyond a certain point, so the argument goes, land yields less and less to additional labor and capital. Otherwise, a growing population would not extend cultivation to additional land. Acknowledging this appears to involve accepting the doctrine that a growing population increases the difficulty of obtaining subsistence.

But if we analyze this proposition, we see that it depends on an implied qualification. It is true in a relative context, but not when taken absolutely. Production and consumption are only relative terms. Speaking absolutely, people neither produce nor consume. They cannot exhaust or lessen the powers of nature. If the whole human race were to work forever, they could not make the Earth one atom heavier or lighter. Nor could they augment or diminish the forces that produce all motion and sustain all life.*

Water taken from the ocean must eventually return to the ocean. So too, the food we take from nature is, from the moment we take it, on its way back to those same reservoirs. What we draw from a limited extent of land may temporarily reduce the productiveness of that land. But the return will go to other land.

Life does not use up the forces that maintain life. We come into the material universe bringing nothing; we take nothing away when we depart. The human being, in physical terms, is just a transitory form of matter, a changing mode of motion.

From this, it follows that the limit to population can be only the limit of space – that the human race may not increase its numbers beyond the possibility of finding elbow room. Remote and shadowy as it is, this possibility is what makes Malthus’ theory appear self-evident.

It’s true that ensuring that our resources sufficiently renew themselves would enable larger populations. We agree that humanity should do what can be done to replenish the Earth’s resources, which includes preventing Tragedies of the Commons. We have proposed several ideas for enabling the Earth to support higher populations.

Unlike George, we aren’t going to be foolish enough to assume that there are no hard limits to how much technology can increase the carrying capacity. And unlike the Cornucopians in general, our proposals are actually realistic and more feasible. Most of our proposals are ideas for using existing resources more efficiently, rather than assuming that we’ll find more resources. They also depend on technologies that already exist, rather than technologies whose inventions have yet to be seen (assuming that they’re even possible to build).

Malthus asserted what he called positive and prudential checks. A third check comes into play with the development of intellect and increased standards of living. This is indicated by many well-known facts. The birth rate is lower among classes whose wealth has brought leisure, comfort, and a fuller life. It is higher among the poor who, though in the midst of wealth, are deprived of its advantages, and thus are reduced to an animal existence. It is also higher in new settlements.

We have a better explanation for why increased wealth correlates with lower fertility in modern times. George’s theory for why poorer people have higher fertility conflicts with all historical, social, or biological evidence.

This shows the real law of population. The tendency to increase is not uniform. It is strong where a larger population would allow greater progress. It is also strong where dangerous conditions threaten the survival of the race. It weakens as higher development becomes possible, and survival is assured. In other words, the law of population conforms with, and is subordinate to, the law of intellectual development.

Sometimes, “intellectual development” evidently isn’t enough to stop overpopulation. We need population control to prevent overpopulation.

When the human population is as large as it currently is, humanity does not gain any conceivable benefits from allowing it to increase any further. To those who disagree, we display a question that was once asked by Al Bartlett in 1998:

Can you think of any thing, any problem, on any scale, from microscopic to global, whose long-term solution is in any demonstrable way aided, assisted, or advanced by having a larger population? Can you think of anything that will get better, by crowding more people into our cities, our towns, our state, our nation, or on the Earth? – Al Bartlett

The simple truth is that a larger population makes life more difficult for all the life that’s currently living. This is true when the population far exceeds the threshold that is necessary for sustaining a complex industrial economy. Life must compete with other life for scarce resources. Now to address the last paragraph:

Any difficulty providing for an increasing population arises not from the laws of nature, but from social maladjustments. These are what condemn people to want in the midst of wealth.

No, the difficulty for providing for an increasing population comes from both the laws of nature and from the limits of human technology, governance, etc. But when the latter fails, the former is always the foremost obstacle.

2.5. Refuting Chapter 9: ’Malthusian Theory “Disproved”’

The question is whether an increasing population necessarily tends to reduce wages and cause poverty. This is the same as asking whether it reduces the amount of wealth a given amount of labor can produce.

Since wages are determined by the supply and demand for labor, and we know that increasing a population will increase the supply of labor, population growth can conceivably reduce wages. Perhaps the demand for labor will also increase if the population increases, but when technological improvements significantly increase the efficiency of labor, it is theoretically possible that the demand for labor may not be able to keep up with the increasing supply of labor.

I assert that a larger population can collectively produce more than a smaller one (in any given state of development).

That’s usually true, but there’s multiple problems that that argument ignores and doesn’t address. First, we have to consider the demographics of the population and the proportion of the working population, out of the total population. Cornucopians ignore that greater wealth enables longer lifespans. If there are more retired people who are living longer and not working at all (which is the case in the 2000s), then this means that the population increased, without adding additional labor to raise the carrying capacity, in proportion to the population increase. The additional labor generated from an increasing working population also probably has diminishing returns.

I assert that, other things being equal, each individual would receive greater comfort in a larger population – under an equitable distribution of wealth.

This is true. That’s why industrial societies require larger populations, and vice versa. We don’t deny any of the following examples in the chapter where greater populations are wealthier than smaller populations. However, we should recognize that their greater wealth wouldn’t be possible without technological advancements and industrialized economies. Advanced technologies and industrialization didn’t exist when Malthus wrote his 1798 essay. When populations increase and the necessary technology for increasing the efficiency of labor doesn’t exist, wages are still likely to fall to subsistence. So, pointing out all those examples still doesn’t refute the fact that additional labor can have diminishing returns for a society in many cases.

Furthermore, infinite growth is impossible, whether that be for populations or for economics. Since humanity will have to decrease its population and economic growth at some point, the complexity of humanity’s technology will also have to decline as well since technological complexity depends on the scale of civilization.

The truth is, wealth can be accumulated only to a small degree. Wealth consists of the material universe transformed by labor into desirable forms. As such, it constantly tends to revert back to its original state. Some wealth will last only a few hours, others for days, months, or even a few years. But there are really very few forms of wealth that can be passed from one generation to another.

That’s one of the reasons why money exists. Money is a way to store wealth now so that it can be used later. Assuming that there is little to no inflation, money is a reliable way to pass wealth from one generation to another. There was also much less inflation during George’s time, before the US went off the Gold Standard in 1971 and installed on an untested and unstable monetary system.

2.6. Final Response To Cornucopian Arguments

No matter what humanity does, the Cornucopians will always proclaim that a mismanagement of resources is the root cause of every instance of overpopulation in human history and every instance of overpopulation that will ever occur. In some cases, it is true that using resources more efficiently could’ve staved off overpopulation for a while. But even when this is the case, no Cornucopian has a sound rebuttal against the argument that populations evolve to reproduce to infinity. The Cornucopian belief that resources can always be used more efficiently makes the following assumptions:

- They assume that humanity is naturally cooperative. But this is not the case. Humans do have the potential for cooperation, but history shows that they just as often have the potential for competition and violence. This is especially true when governments don’t solve problems of cooperation to a sufficient degree, such as the problem of infinite reproduction, which can be solved by population control.

- They assume that more advanced technology and freer markets can always raise the carrying capacity. This is not true.

- They assume that increasing the supply of labor will always raise the carrying capacity. We can’t always assume this.

- They assume that populations don’t reproduce up to the carrying capacity. This is not true.

- They assume that we can reliably predict the future, and they believe that humanity doesn’t need to be prepared for unexpected events. Life happens, so it’s inevitable that unexpected events will happen. We cannot predict everything, so failing to prepare for the unpredictable things is preparing to fail. One of the main benefits of population control is that it’s a powerful counter-measure against unexpected events. Population control would make the future more predictable.

Even when it’s painfully obvious that the most guaranteed way to avoid overpopulation is to have smaller populations, Cornucopians like Henry George will always invent some excuse about how something else was responsible for overpopulation. They will do mental gymnastics and rationalize that massive populations are never the cause of overpopulation. A rational person doesn’t deny that efficient government and advanced technology can expand the carrying capacity when employed correctly. But a rational person also recognizes that it’s not always possible for an ultra-efficient government to exist or for technology to endlessly improve. To a great extent, the opposite belief goes against human nature, the limits of technology, the laws of physics and economics, etc.

Henry George even acknowledged at the beginning of the chapter that that there are always multiple contributing factors to an overpopulation event. So, the most rational position to take is to insist that we cannot separate the factors that caused the overpopulation under any circumstances. To take any other position and say “X was the only factor” is a partisan position. The position that overpopulation can and could’ve always be avoided by managing resources better and improving technology is unfalsifiable. By contrast, I have sound reasoning to believe that life always reproduces to infinity, so my position that overpopulation is inevitable is not unfalsifiable.

Since we can’t always rely on technology, efficient governance, or efficient economics to save humanity, the last line of defense against overpopulation has to be population control. As stated before, the only guaranteed ways to regulate populations are: 1. high mortality rate, or 2. low and/or sustainable birth rate (which may be accomplished via population control). We are never going to escape that aspect of the human condition. In the best interests of humanity, it may be more preferable to have multiple safeguards against overpopulation and its consequences, rather than just one.

2.7. Response to the Publisher’s Foreword

See: Link to the Publisher’s Foreword for Progress and Poverty (edited and abridged by Bob Drake).

When Progress and Poverty was published in 1879, it was aimed in part at discrediting Social Darwinism, the idea that “survival of the fittest” should serve as a social philosophy.

Social Darwinism is Nature, though I prefer the term: biological realism. And just because the namesake of Georgism opposed Social Darwinism, that doesn’t mean that it’s bad.

[Social Darwinism] provided the intellectual basis for 1. American imperialism against Mexico and the Philippines,

The Mexican-American War was arguably one of the most important wars in the history of the United States. The war took away half of Mexico’s potential land (and potential power). It added the territory for California and Texas to the Union, which are currently the two most populous states in the United States (as of 2024). Likewise, it prevented Mexico from reaping the economic benefits of the California gold rush. Texas also wanted to secede from Mexico and join the United States, and that ought to have been justified for anyone who supports democracy and believes in the right to self-governance.

The American conquest of the Philippines was justifiable as well. The Philippines were a territory of the Spanish Empire, so the Spanish-American war only shifted territorial ownership from one empire to another. Ultimately, the more powerful country got to keep the territories. Such is Nature.

- tax policies designed to reduce burdens on the rich by shifting them onto the poor and middle class, 3. the ascendancy of the concept of absolute property rights, unmitigated by any social claims on property,

I fully support attaining the most meritocratic taxation system that we can hope to gain. However, I also recognize that every tax code reflects a balance of power. Sometimes, power prevails over meritocracy in Nature.

- welfare programs that treat the poor as failures and misfits,

I support welfare when it provides the populace with relief from major economic catastrophes (e.g. The Great Depression; earthquake, hurricane, flooding, etc disaster relief).

Aside from those situations, I’d argue that it’s rational to oppose all other welfare. Most other welfare is unsustainable because it creates free-rider problems. Welfare states also worsen dysgenics, penalize productivity (via taxes), and can create unsustainable levels of debt.

- racial segregation in education and housing, and

Segregation may be morally abhorrent nowadays, but it used to exist in the US and South Africa for multiple reasons. I’d even argue that it had multiple important historical benefits. Nowadays, blacks are ~7x more likely to commit crimes against whites than vice versa (See table 13 of the 2021 NCVS report). This is most likely due to genetic differences between blacks and whites. And given that there used to be a lot of hatred and animosity against blacks by southern white Americans, segregation arguably helped protect both black Americans and white Americans from violence. Segregation also prevented race-mixing, which arguably helped maintain the eugenic quality of white Americans, by not diluting them with lower IQ genes. Segregation also helped staved off the harmful anti-white, anti-Western, social justice movements of the early 2000s.

- eugenics programs to promote the “superior” race.

There are no rational arguments against eugenics. Also, eugenics doesn’t necessarily promote racial supremacy, nor do I endorse such a concept.

The intellectual defense of racism is in abeyance, but the economic and political instruments of domination have changed little.

I do support nor condone racism on any grounds.

The renewed defense of taxing wages and consumer goods rather than property holdings, expanded intellectual property rights, and vast imperial ambitions are indications that Social Darwinism is back in full force.

Social Darwinism is hardly back in “full force”. Most people abhor eugenics, race realism, and other Social Darwinist positions these days. All of these positions are likely to be labeled as “Fascism” or “Nazism” by most people.

The revival of Social Darwinism continues to justify social disparities on the basis of natural superiority or fitness. Progress and Poverty, by contrast, reveals that those disparities derive from special privileges.

Most social disparities exist due to genetics.

Many economists and politicians foster the illusion that great fortunes and poverty stem from the presence or absence of individual skill and risk-taking. Henry George, by contrast, showed that the wealth gap occurs because a few people are allowed to monopolize natural opportunities and deny them to others.

It’s more likely that differing genetics are the primary cause of economic inequality. It’s true that unequal land ownership and other inefficient economic policies are the main environmental cause of wealth inequality. It’s also true that Georgism would do a lot to eliminate wealth inequality. However, we also need to recognize that the ability of power-holders to maintain the current system is an expression of the genetic causes of economic inequality.

If we deprived social elites of those monopolies, the whole facade of their greater “fitness” would come tumbling down. George did not advocate equality of income, the forcible redistribution of wealth, or government management of the economy. He simply believed that in a society not burdened by the demands of a privileged elite, a full and satisfying life would be attainable by everyone.

Wealth inequality is natural. Humans have essentially lived under social caste-based societies with low, stable social mobility for nearly all of human history. And even if we did make everyone 100% equal in wealth, then other inequalities would matter more anyway, e.g. genetic inequality, sexual inequality, moral inequality, etc. This makes the goal of achieving greater wealth equality highly questionable. Not only that, but it’s quite possible that the descendants of the current economic elite would eventually be able to recapture the wealth that their ancestors used to have, if it’s true that most wealth inequality is caused by genetic differences.

Instead, it would be more productive for Georgists to learn about the dynamics of social mobility, and what could be done to achieve a more meritocratic society.

2.8. ZC’s Book Review for Progress and Poverty

Note: I posted this book review on GoodReads on 2025 April 8, but I’ll probably update it as I further develop my views on economics. I wrote this book review for the modernized edition of the book, but it still applies for the original version as well.

I think the modernized edition is an improvement over the original since it has better readability and removes a lot of the verbose language. Nevertheless, the language and arguments in the modernized edition are still rather outdated for today’s modern world. Most modern resources for teaching and explaining Georgism are far superior for demonstrating the concepts that readers should understand.

The first 9 chapters of the book are highly fallacious and not worth reading. Chapters 12, 13, and 14 discuss interest, so they probably have fallacies.

Silvio Gesell also managed to refine and improve upon Georgist economic philosophy by identifying currency (and interest) as another major cause of economic inefficiency, in addition to land. Henry George identified the wrong cause and theory of interest, so the parts of the book that talk about interest (mainly chapters 12, 13, and 14) aren’t worth reading since they’re fallacious.

Chapter 39 is very erroneous and ignorant of applied evolutionary biology. Chapters 40 to 44 are out-dated and naive.

So, that leaves only chapters 10, 11, and 15 through 38 as the only chapters in the book that might be worth reading. But I didn’t really need to read them, since I already knew and understood all the core arguments from better articulated resources that I had read. Even then, the economic theory present in them is still inferior to the theory articulated by Silvio Gesell and Gesellian authors. As is often the case, most political theory is overrated, outdated, and inferior to modern writings.

The book was very popular in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and I can see how it was ahead of its time during those periods. But overall, this book is not worth reading, from a modern reader’s standpoint. Lars Doucet’s book review of Progress and Poverty is decent enough for anybody who wants to know the book’s main ideas, although it fails to identify the fallacies and falsehoods within the book.

There is thus no need to read the original book. Most political theory is overrated, outdated, and inferior to more modern writings. There are far better texts, infographics, videos, etc these days.

The only reasons why I’ve wondered about reading the book is that I’ve heard that it used to be so popular, I’ve seen so many contemporary Georgists reference it or say that they’ve read it, and I actually don’t know exactly what Henry George said. But I need to accept that I really don’t need to waste my time trying to further read the book. It’s littered with fallacies regarding interest, the nature of prices, verbose text, and things that just aren’t valuable enough to be worth reading.

Read More: Our Disagreements With Henry George.

Someday, I might also write a rebuttal against Chapter 1 “Why Traditional Theories of Wages Are Wrong”, when I have time. It has a lot of errors and non-sequitur arguments as well. But I’m saving that for a later date for now.

Besides that and what we’ve covered here, another major error made in Progress and Poverty was that Henry George took prices and monetary values for granted. That link contains information and links to other essays that explain why this is a common mistake in economic thought.

3. Why Georgism Implies EPC

3.1. The Connection Between Georgism And EPC

Georgism is the position that income tax, sales tax, property tax, and all other taxes should be abolished and replaced with taxes on land and natural resources (LVT and NRT), which would fund all government services. The idea is that anyone who occupies land must compensate the rest of society for the right to occupy said land. Privately owning land without compensating society for its occupation prevents everybody from being able to use it, which enables rent-seeking. There are many economic and environmental benefits to be gained for any society that implements Georgism.

Note that when we’re talking about “land” here, anything that is a naturally-occurring resource that exists in fixed supply counts as land. The economic sense of land thus includes: geographic land, natural resources, mineral deposits, forests, fish stocks, atmosphere quality, airway corridors, geostationary orbits, portions of the electromagnetic spectrum, domain names, and even a license to have a biological human child, as I shall make the case in this essay.

If we have a solid understanding of population dynamics, and we don’t want the population of our society to exceed the carrying capacity (in the interest of avoiding war, famine, and emigration), then the next step is to establish what we should want the maximum population limit of our society to be. Overpopulation can happen instantly if a sufficiently catastrophic disaster occurs, so it’s a good idea to leave some buffer space between the legal population limit that we declare and the maximum carrying capacity of our environment.

Moreover, if our society has a legal maximum population limit (LMPL), then we’ll have to regulate how many children each citizen is allowed to have, to avoid overpopulation. We can achieve this regulation by mandating that every couple that wants to have a child must obtain a reproduction license, which can be granted if a list of reasonable requirements are meant.

Since there is a fixed supply of reproduction licenses that can be distributed out to everyone who wants to have children, and acquiring the right to have a child is a necessary resource for reproduction, reproduction licenses thus constitute land (in the economic sense), by the definition given earlier. Georgist economic reasoning thus concludes that the fairest solution is to auction off the right to have a child to every member of society who wants to have a biological child. In essence, all the auction money collected from this would constitute the reproduction tax. The money collected from the auction winners would fund government expenditures, and every auction winner would be allowed to have one child for each license that they had purchased in the auction. The more children that a person wants to have, the more money they would have to bid in the auctions. Enforcing Georgist principles as part of a legal code thus generates competition. Eventually, the auction price to buy a reproduction license would settle at a stable amount of money, determined by free-market forces.

We’ve established that reproduction licenses are land, and as expected, they even function like land too. Anybody who occupies geographic land for themselves prevents everybody else from being able to occupy that land. Likewise, if there’s a fixed number of children that can be legally born each year, then every person who has a biological child is doing so at the cost of someone else not being able to have a child of their own. If we want to avoid rent-seeking and bestowing undeserved privileges to anybody who is fortunate enough to acquire land before everybody does, then we need to auction off the land. The auction revenue (land value tax and reproduction tax in this case) would fund the government’s expenditures.

So there we have it. Technically, Georgism by itself does not imply Eugenic Population Control (EPC) because a person also needs to have a correct understanding of biology that leads them to propose legal population control limits on the society. But once both the biological and economic understanding are combined, they complement each other extremely well since both concepts deal with natural resources that exist in fixed supply and aim to increase their conservation.

3.2. More Concise Bullet Summary

Let’s restate all the premises and chain of reasoning of our argument more concisely:

- Infinite population growth is unsustainable. All populations eventually reach their carrying capacities. When this happens, life becomes a zero-sum game.

- Therefore, there should a legal maximum population limit enforced by law, with some buffer space between this limit and the theoretical maximum carrying capacity of the country’s environment.

- Since this implies that people can only have a finite number of children each generation, it makes sense that there should be limits on who is having children and how many.

- This means that there would be an economic rent for anybody who decides to have X number of children. If there is a maximum number of children who can be born each year or five years or so, then anybody who decides to have a child would be doing so at the cost of other people being unable to have children of their own.

- Thus, there is sound reasoning and solid justification for auctioning off the right to have children (which constitutes a reproduction tax set by market forces) for anybody who decides to have children. The reproduction tax is equal to the economic rent to have a child.

- Since there exists: 1. genetic variation in the population, 2. competition to purchase the right to have children at the auctioning price, 3. selection resulting from the winners of the auctions and legal requirements, and 4. reproduction, all the necessary conditions for evolution have been satisfied, so evolution would take place, thus leading the genome to develop eugenic qualities. This is unlike the current world we live in where dysgenics and overpopulation are both rising due to the elimination of selectionary pressures on the human population.

- It follows that a Georgist approach to population control is the fairest and most reasonable way to impose population control on a population of humans, in the interest of avoiding overpopulation.

Since populations naturally reproduce up to the carrying capacities of their environments, the population would spend most of its time in an Evolutionarily Stable State (ESS), so there wouldn’t be any need to worry about whether or not people will have enough children up to the Legal Maximum Population Limit (LMPL). But in the event that the population is significantly lower than the carrying capacity, reproduction would not be taxed at all. Since the population of the EPC country would spend most of its time at the LMPL with marginal fluctuation from one year to the next, the population size would be very constant for many years, decades, or even centuries, assuming that the government doesn’t pass a law to change the LMPL, and no unexpected events like war occur.

3.3. Why Georgism Will Not Function Correctly Without EPC

There are three reasons why a Georgist society would eventually fail if it does not enforce EPC.

- Relying on Georgism to increase the carrying capacity would not solve overpopulation, even if it works as predicted. The additional wealth and natural resources would enable humans to increase their fertility rates, thus bringing the population back to scarcity. No political system will sustain itself without population control because overpopulation poses an existential threat to humanity.

- If a society has Georgism, but no population control, then the Iron Law of Wages still applies to the society, because evolution always selects for high-fertility people. Eventually, the population will increase that it reaches the carrying capacity once more, thus causing wages to fall to subsistence levels. Most people hate living paycheck to paycheck, so few people would view this as desirable.

- If a Citizen’s Dividend (CD) is awarded to every adult citizen, then the most fertile factions of society would collectively receive a greater percentage of the CD as their population increases faster than everyone else (e.g. the Amish). Different subgroups could abuse the CD to subsidize their genes. This would accelerate dysgenics because Georgism alone does guarantee that everybody who has children will be a productive member of society.

On the other hand, if a Georgist government enforces Eugenic Population Control, then: 1. it would prevent overpopulation, 2. wages wouldn’t fall to subsistence because the supply of labor would be limited, and 3. the society would remain stable and self-sufficient. A Citizen’s Dividend (UBI) would increase dysgenics, but enforcing EPC could prevent that from happening.

4. Why Eugenic Population Control Implies Georgism

Land speculation is a form of rent-seeking, and we will need to eliminate all forms of rent-seeking in order for EPC to select people who will create the more wealth for the rest of society to enjoy. If rent-seeking is not eliminated from society, and auction prices remain the primary factor for determining who gets to have children, then it’s possible for someone to get rich by rent-seeking and to use that money to buy many reproduction licenses. This is not what we want. If such a person is allowed to have children, then EPC would be selecting for parasitic freeloaders, not productive people who generate lots of wealth.

Georgism makes land speculation impossible, so a Georgist legal code is required for Eugenic Population Control to work correctly. Supporting EPC thus implies supporting Georgism.

5. The Georgist Approach To EPC

5.1. Why This Matters

Not only do Eugenic Population Control and Georgism both imply each other, but it’s not possible to have one without the other. A society cannot have effective EPC without Georgism, and there cannot be lasting Georgism without having EPC. In order for a society to have EPC or Georgism, it must have both.

Georgism also solves the question of how reproduction tax rates should be set. The tax rates would be determined by market forces, with respect to the supply of the reproduction licenses[2], the demand for reproduction licenses[3], and the price of reproduction licenses, all of which can be displayed on a supply-and-demand curve.

This conclusion gives us more information about how we should implement both EPC and Georgism. If Georgism raises the economic prosperity while reducing the cost of living in the society, then implementing Georgism first would increase the “pull” factors that attract foreign immigrants into the Geostate, which could potentially be dysgenic. In today’s world, restricting mass immigration probably won’t gain popular support unless the populace already supports EPC, so if we value eugenics, then Georgism would ideally be implemented after enforcing a stricter immigration code, in order to protect the eugenostate’s interests.[4]

Fortunately, the increased dysgenics from implementing Georgism first won’t matter too much, as long as EPC is implemented soon afterwards to minimize the effects. Given how taboo it is to suggest eugenics or population control nowadays, it will probably be easier to promote Georgism into the Overton Window first since Georgism would benefit everybody, including normies. If people can understand Georgism, they may be more willing to support EPC, due to the similarities between the two that were explained in this essay.

Figure 1: Maximum Taxation With Perfectly Inelastic Supply, CC BY-SA 4.0, by Explodicle.

Figure 1 differs from the original image since the transparent background in the original image was replaced with a solid white background.

5.2. Under what conditions would the Reproduction Tax not be applied?

If EPC is enforced in a country, and the supply of reproduction licenses (the number of babies that can be born that year) is higher than the number of applicants for reproduction licenses, then there would be no tax on reproduction. In this case, the society and government want to raise the birth rates of the country, so it makes sense to not tax reproduction licenses. This is akin to how there’s no need to tax land or natural resources if there’s enough resources for everybody. There’s no tragedy of the commons if there’s plenty of resources and reproduction licenses for everyone.