Representationalism

The Most Reasonable Philosophy of Knowledge

1. The Nature of Consciousness

Consciousness can be thought of as will and awareness. If one expands, then the other contracts. The best paradigm for understanding how consciousness fits into the physical world is the subject | object dichotomy.

Related Video: How Wolves Challenged Our Understanding of Consciousness.

Related Video: Why Your Brain Blinds You For 2 Hours Every Day – Kurzgesagt.

1.1. The Subject | Object Dichotomy

Main Article: What is Subjectivity? - Blithering Genius

Wikipedia: Subjectivity and objectivity (philosophy)

A subject is a being who has a unique consciousness (will and awareness) and/or unique personal experiences, or an entity that has a relationship with another entity that exists outside itself (an object).

An object is a philosophical term often used in contrast to the term subject. A subject is an observer and an object is a thing observed.

A subject has a mind. Something is “subjective” if it is mind-dependent or perspective-dependent. Subjectivity is not random or arbitrary. Subjectivity is a concept for describing properties of the mind, like knowledge, truth, emotions, value, will, awareness, etc.

A subject can be viewed as both a subject and an object. Philosophy and psychology are the self thinking about itself. This is achieved by viewing subjects from the perspective as if they were objects.

The conditions of being a subject within objective reality:

- Biological Desires for sustaining the subject’s life.

- Truth and Knowledge that provides only a limited scope of reality.

- Free Will (Deterministic as an object, “free will” as a subject)

- Limited lifespan with eventual mortality where all biological processes cease to continue.

- Designed to reproduce (a consequence of evolution).

| Subject | Object |

|---|---|

| Knowledge / Truth | Reality |

| Free Will | Determinism |

| Value | Material Things |

| Consciousness | Materialism |

We cannot understate how important the Subject | Object Dichotomy and its implications are for forming an accurate and coherent philosophy and understanding of the world.

Note: It seems that it’s easier to learn the subject | object dichotomy inductively rather than deductively, i.e. by learning the more specific applications, and only then looking at the big picture.

Further Reading: Wikipedia: Neurodiversity.

Further Reading: The Typical Mind Fallacy – LessWrong.

1.2. Different Types of Thought

Thought is defined as any mental process that the mind can consciously think about.

- Concept

- Abstract Concept

- Concrete Concept

- First-Level Concepts

- Higher-Level Concepts

- Concepts of Consciousness

- Conjecture

- Decision

- Definition

- Lexical (Dictionary) Definition

- Stipulative Definition

- Theoretical Definition

- Operational Definition

- Precising Definition

- Ostensive Definition

- Intensional Definition

- Genus–Differentia Definition

- Extensional Definition

- Ostensive Definition

- Enumerative Definition

- Recursive Definition

- Persuasive Definition

- Explanation

- Hypothesis

- Idea

- Logical argument

- Logical assertion

- Mental image

- Model

- Simulation

- Sensory Input

- Percept / Perception

- Emotions

- Meditation

- Meditation is the practice of training one’s attention to achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm state. Focus awareness meditation is the practice of focusing one’s attention on just one thing, such as breathing.

- Meditation

- Premise

- Proposition

- Syllogism

- Theory

- Thought Experiment

- Imagination

Note: I still have more thinking to do regarding how each of these are defined and what should be included in this list.

1.3. Different Types of Intelligence

Wikipedia: Howard Gardner’s Theory of Multiple Types of Intelligence

- Logical-Mathematical Intelligence

- i

- Musical-Rhythmic Intelligence

- i

- Visual-Spatial Intelligence

- i

- Verbal-Linguistic Intelligence

- i

- Bodily-Kinesthetic Intelligence

- i

- Interpersonal Intelligence

- i

- Intrapersonal Intelligence

- i

2. Introduction To Truth And Knowledge

- Theories of Knowledge - Blithering Genius

- Views - Blithering Genius

- The Illusion of Truth - Veritasium

- The Frequency of Patterns and Stimuli affects how true or false we judge things in the world.

- Cognitive Load

- Cognitive Ease

- Cognitive Difficulty

- The Mere Exposure Effect

- Epistemology: The Puzzle of Grue - Wireless Philosophy

- What Is Random? - VSauce

- What Is Not Random? - Veritasium

- What Seems Random? - Veritasium

- What is Truth? - AntiCitizenX

I like the last video, but I recommend ignoring how he promotes the Pragmatist Theory of Truth at the end since Pragmatism is incorrect. The cerebral cortex is a generic pattern-abstraction and recognition device that learns from embodied experience. In order to learn anything, we need to observe data and detect patterns that help us understand the data.

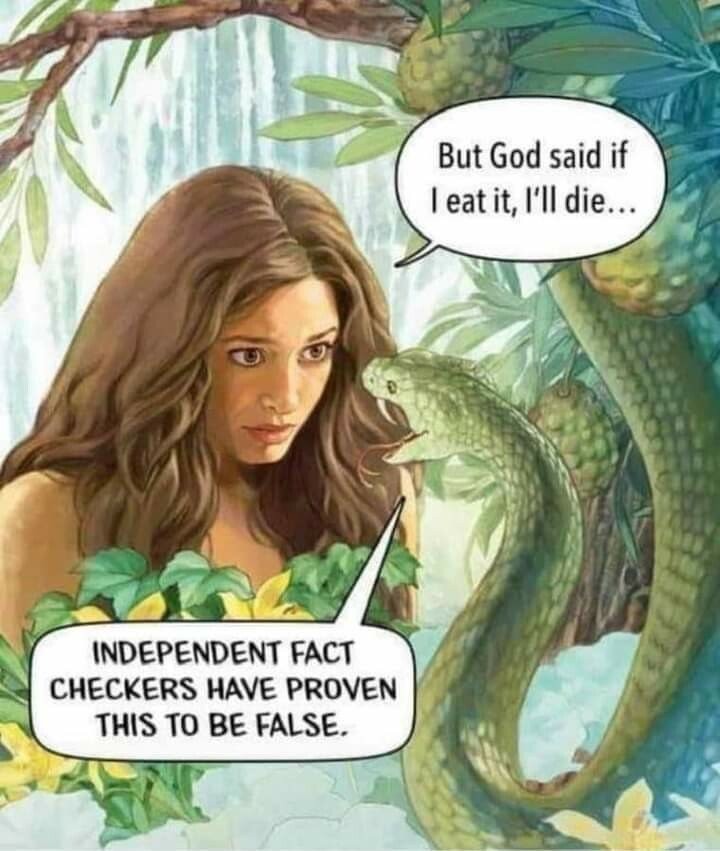

Since it’s impossible for someone to know literally everything, it’s also impossible for there to exist a universal ends-all-be-all fact-checker for truth. The best way for truth and fact-checkers to work in a society would be for the most dominant fact-checkers to cite the primary expert/institution/authority/knowledge/facts that they appeal to when determining the truth value of something. Likewise, there should be several competing truth fact-checkers, just like how it’s a good idea for there to be several competing products on the market, several competing currencies, or several competing reviewers/peer-reviewers. It’s up to everyone in society to decide who they want to agree with. Fact-checking is not easy.

2.1. Empiricism, the Origin of Knowledge

All knowledge originates from observing reality. We learn about reality by sensing it, making mistakes, and learning from those mistakes. All learning is a process of inductive reasoning.

Empiricism and Rationalism don’t (and shouldn’t) contradict each other. Sensory Input is just one part of the Reasoning Process.

2.2. The Three Nested Definitions of Knowledge

The ability to predict (the ability to do the reasoning process).

The most specific definition is the ability to predict, and that involves models and representations of reality. Prediction requires representing reality. There’s no such thing as prediction without a model.

“To forecast, foretell, or estimate an unknown event on the basis of reasoning and existing knowledge.”

The ability to do things (procedural knowledge).

We might say he knows how to skate, he knows how to dance, he knows how to sink a 3-pointer, etc.

The ability to fit form to function (FFF) (the most general definition of knowledge).

For example, We might say the flower “knows” how to attract bees.

These three things are nested in the sense that the ability to predict enables you to do things, and the ability to do things is part of this more general biological concept of fitting a form to a function. All three of these definitions imply that any acquired knowledge under any of these three definitions is ultimately aimed at solving problem. – Blithering Genius, Epistemology Discussion

A fourth definition of knowledge could be descriptive knowledge, which can be used to aid the actions of doing the procedural or prediction based definitions of knowledge, although it cannot be used to solve problems by itself alone.

Related: The Problems With Justified True Belief (JTB).

Since the ability to predict implies: some sort of input[1], concepts, and the logic process step, the ability to predict is basically the same thing as the reasoning process.

Note that there should be a further distinction of sensory, emotional, and experiential knowledge (SEMEX).

Just as reason is useless in a world that is completely absent of problems, knowledge would also be useless if there are:

- No problems to solve,

- No problems that can be solved, or

- No problems that the reason-endowed being wants/chooses to solve.

Criteria that problems must meet to be worth attempting to solve:

- There is a problem to solve,

- It is possible to solve the problem, and

- Some reason-endowed being would want/choose to solve the problem.

2.3. The Nature of Ideas, Concepts, and Properties

- An idea is anything that you can possibly think of.

- A concept is similar to an idea, but different since it has a term or lexeme to specifically identify it.

- Concepts also usually exist within systems and frameworks that relate other concepts together for the brain’s model understanding of the whole framework.

- Every concept has an implicit (or explicit if more conscious) definition in our brains.

- Every concept has a definition

- All properties are technically concepts by this definition since we can think about them.

- Properties are simpler concepts that can be identified as being parts of more complex concepts.

- Properties are used to define complex concepts.

- Properties are simpler concepts that can be identified as being parts of more complex concepts.

- Complex concepts may be defined by properties as part of their definition, and properties have their own definitions.

- So the definition of complex concepts that are defined by properties is really just a definition composed of other definitions.

- If more complex concepts are described in simpler and simpler terms until there are no properties left to describe them, definitions that are free from properties are used instead.

- At some point, things just can’t be more simply described, so definitions are used to communicate what our brains are indescribably and abstractly thinking about.

- Definitions have two purposes:

- To explain things that we don’t understand.

- To provide concrete descriptions of what we are talking about.

- Every known concept and property has a definition in our brain, even if we can’t verbally describe it.

- Definitions have two purposes:

See: The Role of Concept Formation in the Reasoning Process.

2.4. The A Priori and A Posteriori Distinction

| Epistemology | A Priori | A Posteriori |

| Language | Analytic | Synthetic |

| Metaphysics | Necessary | Contingent |

| Explained | Cannot be false | Can be false |

| Explained | Definition-based | Empirical/Experience-based |

The a priori and a posteriori distinction was central to Immanuel Kant’s entire philosophy. Kant proposed that Knowledge of Metaphysics is Synthetic, A Priori Knowledge. Metaphysics is supposed to be definition-based knowledge about the world that seeks deeper meaning.

- For example, it is one thing to know that a triangle has three sides, but it’s another thing to know that all the angles in a triangle add up to 180 degrees, and is thus equivalent to traveling in the exact opposite direction.

- In this example, a triangle is defined as having three sides because that is the most distinguishing characteristic that the human mind uses to define a triangle when first learning about it (distinguishing characteristics are most important for classifying and categorizing concepts).

Kant believed that the pinnacle of Metaphysics and Mathematics was to understand the world’s less obvious characteristics, beyond its most obvious characteristics. Metaphysics isn’t supposed to be a bunch of empty definitional truths, metaphysics is supposed to discover truths that are necessary and universal. Metaphysics is supposed to extend our knowledge, to be ampliative.

Informative Video: Kant On Metaphysical Knowledge- Wireless Philosophy.

Philosophical Distinctions Table

| Metaphysics | Epistemology | Language |

| Necessary | A Priori | Analytic |

| Contingent | A Posteriori | Synthetic |

Philosophical Distinctions Table (Transposed)

| Metaphysics | Necessary | Contingent |

| Epistemology | A Priori | A Posteriori |

| Language | Analytic | Synthetic |

2.5. The Raven Paradox

Raven Paradox - Wireless Philosophy

Even though there are lots and lots of wrong philosophical positions, it is still important to know them, the arguments in favor of them, and why they are all wrong because this helps us to better understand the correct philosophical positions by contrast. Due to the nature of belief networks, the only way to determine the best philosophical positions is to rigorously argue them back and forth until we inductively determine the best ones.

2.6. The Sorites Paradox

The Sorites Paradox: If a heap is reduced by a single grain at a time, the question is: at what exact point does it cease to be considered a heap?

The Sorites Paradox is related to the Raven Paradox. The proposed solutions (including ones by analytic philosophers) to Sorites Paradox don’t actually solve it. They’re just playing language games.

Knowing how to solve the Sorites Paradox is helpful for understanding:

- The Emergence of Consciousness

- Races as Clusters of Genes

- Dialect Continuums

- The Ship of Theseus

- Slippery Slope Fallacies

- Wittgenstein’s Concept of Family Resemblance The concept of “trees” fits [Wittgenstein’s Family Resemblance](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Family_resemblance).

- Many other things

3. The Representationlist Theory of Truth

This may also be called the Information Compression Theory of Truth, or the Model of Models Theory Of Truth. I don’t have an exact name for it.

Different levels of truth are distinguished by lossey information compression (information is lost the more simplified the knowledge is).

If Knowledge is non-lossey, then the parimoniousness of the knowledge is additional knowledge, because high-quality knowledge is supposed to be parsimonious.

Relevant Articles:

Sometimes you have to exaggerate things in order to show/demonstrate the truth. For example, the NPC meme exaggerates how many people don’t think for themselves, and just believe, follow, and do what everybody else does. This demonstrates what most normies are like.

3.1. Why Objective Truth Doesn’t Exist

“Objective truth” does exist if we’re talking about the other more common sense of objective, i.e. describing reason-based facts about the material world, rather than something emotional, whimsical, or otherwise arational. However, that’s not the sense of “objective”, that we are focusing on in this section.

To put it most concisely, the reason why objective truth does not exist is that it’s not possible to have absolute, omniscient knowledge of reality. Conscious minds can only have subjective, perspective-dependent models of objective reality. No proposition can ever be truly be labeled as “objectively true” because it’s always possible to be wrong about that said propositions if further knowledge of reality invalidates that proposition’s truth value assignment. Truth is essentially the same thing as knowledge, because whatever people know is what they will assert to be “true”.

There is no foundation for truth, any more than there is a biggest number.

- Suppose that X is the biggest number. Now add 1 to X. X + 1 is bigger than X. Thus, X is not the biggest number.

- Suppose that F is the ultimate foundation of truth and value. Now question F. Thus, F is not the ultimate foundation of truth and value.

– Blithering Genius, Lucifer’s Question

“There is no truth.”

This is a valid performative contradiction. Whether truth is subjective or objective, saying this statement contradicts itself.

“(The truth is that) there is no objective truth.”

This is not a true performative contradiction since truth is relative by definition. For that reason, asserting this statement does not have to assume that propositions are objectively true. It can be shown more clearly why there is no contradiction in this statement if we rephrase the statement with two other statements that have equivalent meaning:

“There is no objective truth.” = “Nothing is objectively true.”

“Nothing is objectively true.” = “All truth is relative.”

A common theme among mastering different academic fields is to understand the finer details of something. The goal of mastery is make all the tiny, implicit details explicit and rigorous. Examples:

- For math, everything must be rigorous and verbose. One reason is to avoid assuming things that need to be proven

- In programming, telling instructions to the computer often requires lots of tiny steps we would never think about.

- When learning a foreign versus a natural language, one must be aware of lots of small details often overlooked by natives.

- For physics, all small details must be considered when calculating physics problems, though they are often ignored in idealized models and situations used for teaching physics concepts.

3.2. Example: “The Sky Is Blue”

A common phrase that many people utter for asserting the supposed obviousness of objective truth is “The sky is blue”, but this is ironically a great example for demonstrating how truth is all about information compression. For one thing, the sky isn’t always blue. Sometimes, it has orange/sunset colors, sometimes it’s gray when it’s cloudy and raining outside, sometimes it’s pitch black at night, and it can even appear red during wildfires, yellow near hurricanes, or white if there’s nothing but clouds. Since Truth is information compression, saying that “the sky is blue” omits the information that the sky isn’t always blue all the time (because it’s the simplest statement we can say about the sky’s color), even if it may be the case that the sky is blue most of the time.

Whether or not the sky is blue also depends on a person’s subjectivity, namely the color receptors in a person’s eyes and how their brain perceives color. It also depends on the spatial perspective that the sky is viewed from, like if you’re viewing the sky from above below or at some angle.

Furthermore, the vast majority of the world’s languages don’t make a native distinction between blue and green, most likely because the human eyes have fewer blue cones for detecting blue light within them, in comparison to the number of red cones. Many languages don’t even have a native word for “blue/green”. And to make things even more complicated, Russian makes a native three-way distinction between green, light blue, and dark blue.

- Green = зеленый

- Light Blue = голубой (also incidentally the term for gay)

- Dark Blue = синий

So, Russians would say that the sky is “light blue” or “cyan”, instead of just “blue”, if they are making the simplest, most information-compressed statement about the sky’s color.

The two main takeaways here regarding the complexity of truth are: 1. truth exists at different levels of provided information, and 2. the specificity/ambiguity of language affects the truth values of propositions. If we insist that the statement “the sky is blue” is definitively and unquestionably true, then we are omitting important information about the sky and choosing to be willingly misleading about it. Since the Correspondence Theory of Truth is unable to account for situations where a subject believes a proposition to be true when it’s actually false given more information about reality, this implies that it’s not sufficient enough for understanding the true nature of truth.

The actual best answer to what color the sky is that it depends on the location, the time of day, and the atmospheric conditions, but people don’t typically say that because it requires more words (information) to say. The other reason is that the phrase that the sky is blue has been repeated so many times is that most people’s minds are classically conditioned to believing that it’s obvious statement.

Note: Technically speaking, what we experience as “blue” isn’t really a property of reality. Blue isn’t real. Blue is just a color that we experience as a qualia, so this isn’t an example of information compression being applied directly towards reality. Nevertheless, the colors that people perceive are highly intersubjective and highly correlated, so this example is still a good example of information compression present in language. A better example of information compression applied directly towards reality (without being partially defined through intersubjectivity) would be: “The Moon is round”.

3.3. Example: “The Earth Is Round”

Most people would describe the Earth as being shaped like a sphere. But the Earth is technically better described as an oblate spheroid since the speed at which the Earth rotates causes the mass around the equator to be farther away from the center of the Earth, compared to all other points around the Earth. Since the Earth is close enough to being shaped like a sphere, and since spheres are a more familiar concept that is easier to understand, nearly everybody refers to Earth as being a sphere in casual discourse.

3.4. The Extent of Truth

Propositions can also be “mostly true”, “somewhat/kind of true/false”, or “mostly false”. In these situations, it is either the case that:

- Some of the proposition’s components are true while the other components are false, or

- There is too much information compression of reality to the extent that the proposition model reality very inaccurately, or

- Both [1] and [2] to some extent each.

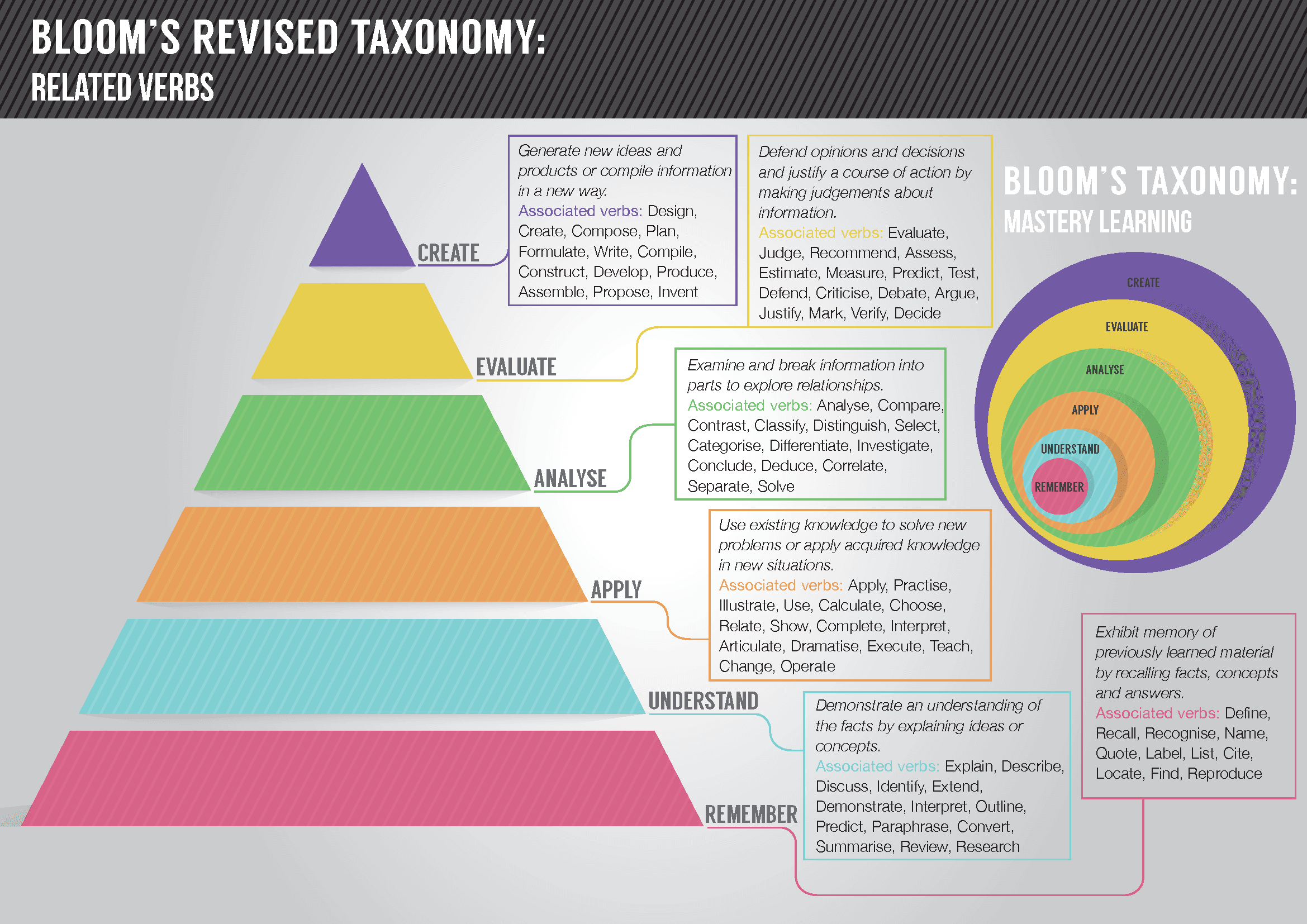

3.5. Bloom’s Taxonomy

3.6. An Example of Information Compression

Among the first conceptions of the Earth’s position in space was Ptolemaic system and epicycles. Further knowledge revealed that the Earth actually orbits the Sun, and the Heliocentric Model was formed. Later, the center of the Milky Way Galaxy was discovered, and it was realized that we live in an ever expanding, unimaginably huge universe.

Each of these different conceptions of Universe not only vary by their accuracy, but also by the amount of information gathered about objective reality that is compressed into the mental models formed from sensory experience. Even if the Ptolemaic Model is clearly wrong with the modern knowledge that we now have about the Universe, it was formed during a time when people could only gaze at the stars and notice that the stars in the sky would vary depending on the time of day and time of year. So if that’s the only information we have to base our model of the Universe on, that model is still “true” according to that limited sensory experience of the Universe. When more information is gathered about the Nature of the Universe, the simpler model becomes false because we have more information to make a truth judgment that is more representative of reality.

3.7. A Second Example of Information Compression

3.8. Examples of False Beliefs formed from Incomplete Knowledge of Reality

This is a small sampling of all the inaccurate thoughts ever brainstormed in history:

- The universe is controlled by a powerful all-mighty god.

- The universe revolves around the Earth.

- The universe is composed of earth, water, air, and fire.

- The species of the world developed according to creationism.

- The Earth is flat.

- The brain is responsible for blood circulation and the heart is responsible for our thinking and thoughts.

- The bones in an embryo are the first structures to develop.

- The expansion of the universe is slowing down due to gravity.

- The great dinosaur extinction was caused by a violent volcano.

- The best system to guarantee human rights is communism.

- Supernatural gods are responsible for the sun, moon, and every other unexplained phenomenon in this universe.

We must keep in mind that all these inaccurate beliefs were formed from incomplete models of reality.

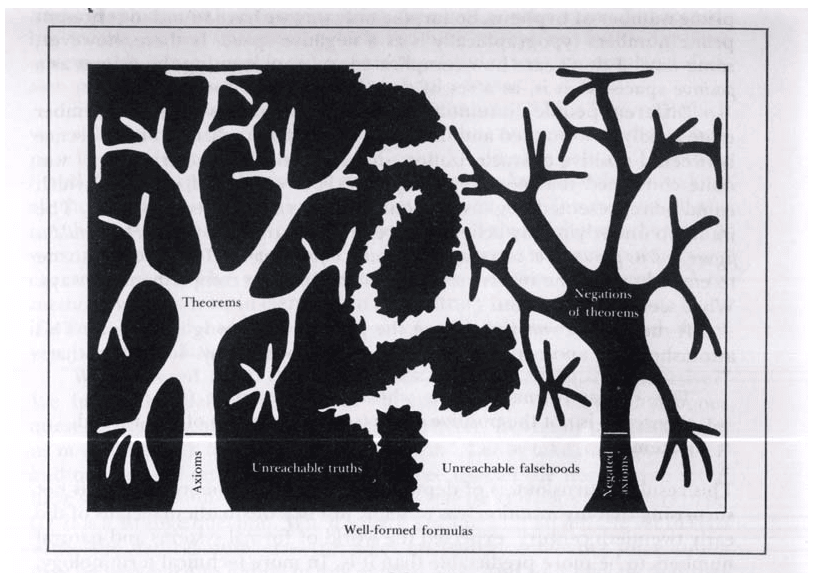

3.9. Unfalsifiable / Undecidable Concepts

“Unfalsifiable” or “Undecidable” is defined as “Not able to be proven false, but not necessarily true”. “Undecidable” should not be thought of as a “truth value” in the way “true” and “false” are. Rather, there is a class of truth values which are not “true” or “false”, all of which are called undecidable. All true statements are equivalent, all false statements are equivalent, but not all undecidable statements are equivalent to each other. A conjecture is undecidable, relative to some formal system, if neither it or its negation can be proven within that system.

Read More:

- What is the Abyss?

- Lucifer’s Question

- What is Value?

- The Nihilist and the Carpenter: A Dialogue for Explaining Nihilism

- Evaluating Tabula Rasa

Video: Why You Should Believe More Conspiracy Theories - Alternative Hypothesis.

4. Other Theories of Truth

4.1. The Problems with Justified True Belief (JTB)

Justified True Belief doesn’t define what “true”, “justified”, or “belief” (knowledge) are. JTB also doesn’t say anything about how knowledge is acquired from sensory experience, which is a major flaw.

The three nested definitions of knowledge are superior to Justified True Belief (JTB):

- They don’t require defining terms like “truth”, “belief”, or “justified”.

- The definition of prediction implies that prediction must be done based on given information within some scheme. So unlike JTB, defining knowledge as the ability to predict is not far removed from sensory experience.

- This definition of knowledge also doesn’t conflict with any of the Gettier Problems.

For a really clear example of knowledge that doesn’t fit the JTB definition, there is language. Knowing Japanese is a kind of knowledge, but no one would call that a “belief”.

4.2. The Problems with the Correspondence Theory of Truth

Also see: Ayn Rand took the Correspondence Theory of “Truth” For Granted.

The correspondence theory of truth assumes that truth is objective and that it exists outside the mind, so it proposes no meaningful difference between truth and reality. Under my representationalist theory of truth, there is no meaningful difference between truth and knowledge because they’re both recognized to be subjective concepts. Both theories of truth/knowledge agree that knowledge and reality are definitely different from each other.

The main problem with describing truth as “conforming to reality” is that there can be no universal, infallible decider for truth since not everybody can agree on what the “Truth” is. Determining “Truth” faces the same exact obstacles that must be faced with determining “Knowledge”. Strangely, most people acknowledge that it’s possible for knowledge to be wrong when admitting that it’s not possible to have omniscience or infallible knowledge of reality, yet they still describe knowledge and truth as “corresponding” to reality. Knowledge and truth cannot correspond to reality if they’re wrong, so it would be more accurate to say that knowledge and truth represent a (fallible) model of reality, from the perspective of a subject.

Truth claims are about objective reality, but there is no way to objectively verify or falsify them. We subjectively verify or falsify them, from our own perspectives, based on the data we have available to us, and using the mental abilities that we possess. At most, people can build a mental model of what they think reality is by sensing it, making mistakes, and correcting those mistakes. If the model is wrong, then they can and should correct their knowledge to form a more accurate model of reality. Beyond that, we can’t know much else about what reality is like because we cannot escape our subjectivity.

“A proposition is either true, or it isn’t. And your model is flawed, or it isn’t”

This statement is wrong as soon as it left the gate. By using the word model, it automatically implied that Truth isn’t about whether a statement corresponds to reality. Truth is about models of reality.

Relevant Reading: What is Subjectivity? - Blithering Genius

4.3. The Problems with the Pragmatist Theory of Truth

AntiCitizenX’s video promotes the Pragmatist Theory of Truth in the last several minutes, but it’s misguided. The Pragmatist Theory of Truth is invalid because it is circular. It assigns truth values according to value judgments. However, value judgments depend on truth judgments, so this only causes an infinite regress. It also begs the question of what is knowledge.

If someone does not have enough information to make the best decision possible, they are not using the Pragmatist Theory of Truth to navigate themselves through life. What they are actually doing is they are using compressed (incomplete) information to form the premises that are used in their decisions. Not everything that we gather about reality from our senses is the big picture of reality is. We often only have a very simplified understanding of reality for many different things.

When we do make mistakes, it’s because the model of reality that we have in our minds is not comprehensive enough. Different truth judgments result from people having levels of understanding and models of reality that vary in their level of details.

Under this understanding of truth, the essential reason why “objective truth” doesn’t exist is because it’s not possible to create a hypothetical model of reality that has 100% accurate precision for all its details. Or in other words, it’s not possible to be omniscient and know everything there is to know about reality because that is a fundamental condition of being a subject (philosophical).

Models are not supposed to be absolutely true. Models are true in a matter of degree, since models (often generalizations) can be very abstract to their particulars.

4.4. The Consensus Theory of Truth

The Consensus Theory of Truth is decided by what group of people collectively affirm to be true. It cannot stand by itself since each person within the group of people (including the people who agree with the consensus) each arrived at their verdict via the Information-Compression Theory of Truth, which works on individual scales. Nonetheless, the Consensus Theory of Truth has popular appeal in many situations, especially when it’s most important that decisions should be made based on popular support. For example, the Consensus Theory of Truth is often used in court systems and in informal situations that have a similar nature to deciding guilt verdicts.

4.5. “The Wikipedia Theory of Truth”

The Wikipedia Theory of Truth proposes that Wikipedia is more likely (but not guaranteed) to be correct than most opinions out there. The justification is that Wikipedia was created by a consensus of dozens to hundreds or even thousands of well-educated people who tend to be smarter than the average person, and are presumably “experts” in their own fields, since many are members of Academia.

From January-November of 2021, this was more or less the theory of truth that I operated under. After spending hundreds of hours binge reading Wikipedia articles, I had major plans to learn Wiki Markup Language and become a Wikipedia editor. I would’ve gone through with that, if I hadn’t changed my plans in favor of creating and working on this website instead.

I eventually rejected the Wikipedia Theory of Truth when I read Blithering Genius’s essay, Why Most Academic Research Is Fake. At that point, I realized that Wikipedia can’t be trusted because Academia is not infallible. In fact, Academia is rigged and as susceptible to ideological biases as any other person out there. When I went through this phase, I was probably the most humanist/leftist that I had ever been in my life, but I’m glad that I eventually saw through it and corrected my beliefs. Since then, I’ve also written a sequel essay that further elaborates on the problems with Academia and what could be done to reform and fix it.

The Wikipedia Theory of Truth is ultimately based on the consensus theory of truth, since it depends on a consensus of editors, academics, etc. Thus, it also inherits the problems with the Consensus Theory of Truth. That is, it cannot stand by itself as a comprehensive Theory of Truth.

4.6. The Meaninglessness of the Standpoint Theory of Truth

When people are making exploitative rhetoric, they often compare injustices to slavery or the Holocaust. Conversely, when people who oppose these comparisons hear them, they often respond by saying something like “That’s offensive to actual Holocaust survivors or actual slaves”. However, if we’re going to take the Standpoint (STFU) Theory of Truth for granted, there are plenty of examples for showing how ridiculous it is.

- Example of a slave who claimed that taxation is worse than slavery: Former Slave: Frederick Douglass.

- Example of a Holocaust survivor who compared modern slaughterhouses to the Holocaust: Vegan Holocaust Survivor: Alex Hershaft.

- Example of a Holocaust survivor who compared the COVID-19 lockdowns to the Holocaust: 92 year-old Holocaust survivor compares COVID response to Nazi Germany.

- Example of a Holocaust survivor who compared Islamic indoctrination as using the same indoctrination tactics used in Nazi Germany: [I can’t remember the name of the person who made this comparison, but if I find it, I’ll post it here.]

The point of this list is that if you look hard enough, you can always find an example of someone who went through a heinous tragedy who compares a perceived form of oppression to their own experiences. Standpoint Theory has to take everyone’s experiences and perspectives for granted, so these people’s perspectives are just as valid as any ideologue’s perspective. Hence, it’s meaningless to compare perceived hardships to sacred moral narratives like slavery or the Holocaust. Conversely, it’s equally meaningless to attempt to use standpoint theory to argue against such comparisons since we can always find someone who went through the actual hardships who agrees with the comparison.

To quote from Blithering Genius on Standpoint Theory:

Standpoint theory is basically the belief that marginalized groups have special insight – that their experiences are more truthy, because they are oppressed or something. In other words, it is complete bullshit. Standpoint theory isn’t a theory of knowledge. It’s a rhetorical trick to “win” a debate by retreating into the swamp of relativism and solipsism. It’s like saying “You can’t see your privilege because you are a white male, so let me tell you about it”. Essentially, it is the demand that you shut up, listen and believe.

Standpoint Theory has gotten so ridiculous that the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has insisted that other traumatic events cannot be compared to the Holocaust. In their moralist worldview, only the Holocaust can be the worst event to have ever happened in human history because the Holocaust is their favorite thing to virtue-signal about.

The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum unequivocally rejects efforts to create analogies between the Holocaust and other events, whether historical or contemporary. That position has repeatedly and unambiguously been made clear in the Museum’s official statement on the matter – a statement that is reiterated and reaffirmed now.

The Museum further reiterates that a statement ascribed to a Museum staff historian regarding recent attempts to analogize the situation on the United States southern border to concentration camps in Europe during the 1930s and 1940s does not reflect the position of the Museum.

The Museum deeply regrets any offense to Holocaust survivors and others that may have been engendered by any statement ascribed to a Museum historian in a personal capacity.

This poses a problem for other moral ideologues who insist that their favorite thing to virtue-signal about can and should be compared to the Holocaust. Since standpoint theory hardliners will argue and virtue-signal against each other about their sacred moral narratives, it’s all just more evidence that standpoint theory is not a meaningful or epistemically sound theory of truth.

5. Evaluating Platonism

If you’d rather read an essay evaluating Platonism instead of a list of bullet points, we recommend “Theories of Knowledge” by Blithering Genius.

5.1. Arguments Against Platonism

Arguments Why The Platonic Realm Does Not Exist:

- The Platonic Realm doesn’t have any explanatory power. The representationalist theory of knowledge is able to explain just as much about epistemology or metaphysics, while also being more parsimonious. Representationalism proposes that our subjective models of objective reality and the associated sensory data and reasoning that generates said models are stored completely within systems of reasoning that exist within our own minds.

- Why does a Platonic Realm containing every possible pattern have to exist, when we can instead understand that patterns are information stored in the brain about the characteristics and relations about many different things (genes, mathematical structures, etc) that exist within the physical world?

- If the Platonic Realm doesn’t exist physically, then where does it exist?

- Where is the empirical evidence that the Platonic Realm exists?

- Where is the empirical evidence that ontological primitives exists?

- How do we have access to the Platonic Realm?

- Why do we have unequal access to all the propositions in the Platonic Realm?

- If there is a Platonic Realm, then why are so many situations where we can’t perfectly model natural phenomena?

- How would Platonists verify truth propositions under their theory of truth? Anytime someone asserts that a statement is “true”, they’re implicating the subject-object dichotomy, because they’re asserting that the statement is true according to their mental model of reality.

- How are the arguments in favor of the Platonic Realm any different from the fallacious Transcendental Argument for God (TAG)? The TAG proposes that there has to be a God for us to understand anything, and Platonists are arguing that there has to be a Platonic Realm for us to have knowledge.

- If we should assume that there are aspects of reality that are not empirically observable without evidence for their existence (e.g. the Platonic Realm), how is this any different from arguing that we should believe in an omniscient omnipotent God, when God is not empirically observable either (under the most common definitions of “God”)?

- Believing in a Platonic Realm does not prevent an infinite regress of knowledge, since it’s actually an Inverse Homunculus Fallacy.

- You don’t solve the problem of meaninglessness by attaching it to an ontology that’s assumed to exist. You give terms meaning by grounding them in embodied experience.

- The methods that we use to understand, explain, and present mathematics (e.g. the mathematical notations, symbols, equations, proofs, the graphing and visuals, etc) are clearly invented. For example, most people use Arabic numerals to represent numbers nowadays, but in the past, they also could’ve been represented using Roman numerals or abacuses. Likewise, the Newtonian notation for differentiation was the first to be invented, but Leibniz notation and other notations were later invented for representing differentiation more efficiently. There’s also many different ways to visually represent mathematical phenomena and do mathematical reasoning, and it’s widely accepted that there are often multiple different ways to arrive at the correct answer. These all suggest or imply that mathematics exists in the mind, not objective reality.

- It’s true that Mathematics is applicable to many different fields of science and knowledge in the real world, but I’m not convinced that this implies that mathematics is built into the nature of the Universe. Whenever mathematics is used to model reality, a parsimonious set of axioms is proposed and theorems are derived to create a mathematical theory(ies) for modeling real world phenomena. Whenever axioms don’t model a particular phenomenon correctly, mathematicians simply add, remove, or change the axioms until they’re able to model the phenomenon correctly. If many, many different sets of axioms must be formulated to model everything within objective reality, this seems to imply that mathematics is actually built into the mind, rather than being a property of the Universe. Human minds are fully responsible for adapting mathematics to model reality, however they perceive it.

Believing in a Platonic Realm only creates more unanswered questions than it solves. Occam’s Razor is sufficient to conclude that the Platonic Realm simply doesn’t exist, since it’s easier to explain truth as being a model representation of reality.

5.2. Arguments For Platonism

Arguments Why The Platonic Realm Does Exist:

- It supposedly gives explanatory power for proving or disproving existential and universal propositions within certain frameworks.

- A Platonic Realm is supposedly necessary in order to prevent an infinite regress of knowledge.

- Gödel’s Completeness Theorems allegedly affirm the existence of unfalsifiable and undecidable statements.

5.3. Arguments why the Objectivity or Subjectivity of Truth is Unfalsifiable

Arguments Why The Existence of the Platonic Realm Is Unfalsifiable:

- The nature of truth makes it impossible to prove whether some statements are true or false. Humans also have limited knowledge of reality.

- Neither side has any arguments that definitively disprove the other’s claims. Both sides make appeals to intuition.

- Note: I actually agree with this argument, but I don’t believe that it disproves the representationalist, cognitive natalist theory. I believe that all knowledge is ultimately based on intuition, so the most rational thing to do must be to accept the theory with the most persuasive arguments, and hence the greatest intuition.

6. What is Mathematics?

Mathematics is a system of reasoning for number, quantity, space, and change, given a set of premises.

Mathematical foundations is “how”, philosophy of maths is “why”.

… the sciences do not try to explain, they hardly even try to interpret, they mainly make models. By a model is meant a mathematical construct which, with the addition of certain verbal interpretations, describes observed phenomena. The justification of such a mathematical construct is solely and precisely that it is expected to work–that is, correctly to describe phenomena from a reasonably wide area – John Von Neumann

When people use the term ’Mathematics’, they usually mean at least one of three things:

- Using reason, logic, theorems, and axioms to prove new theorems that can enable us to make conclusions about abstract situations, or invent new mathematical methods for doing things.

- Modeling a situation using abstract objects.

- Solving the abstract model of a situation, which often pertains to a real situation.

These three things can be summarized as: 1. creating the tools to solve a problem (theory building), 2. modeling a problem, and 3. solving a problem (problem solving).

Recommended Reading: Reality Realism by Sean Carroll.

6.1. Commentary on Reality Realism by Sean Carroll

See: Reality Realism by Sean Carroll.

In Morality & Mathematics, Clarke-Doane provides a list of features that a field should have in order that we should be realist about it. These include Aptness (typical sentences are true or false), Belief (sentences conventionally express beliefs), Truth (some atomic sentences are true), Independence (truths are independent of human minds), and Face-Value (sentences should be interpreted at face value). Interpreting “2+2=4” and analogous statements as summaries of physical facts would seem to be straightforwardly compatible with Aptness, Belief, and Truth. (It is true that two apples, augmented by two more apples, leaves us with four apples.)

One could worry about Independence – the convenient summaries provided by mathematical statements are convenient for humans, after all. An omniscient and omnipotent observer wouldn’t need recourse to any kind of summaries; they could just know and reason about all of the physical facts. But the facts that underwrite the summaries are still there, whether any agents notice them or not. An absence of human minds doesn’t affect the combination properties of apples. So Independence appears to be satisfied.

– Sean Carroll, Reality Realism, page 5

I agreed with essentially everything in the essay, up to this quote. However, I disagree with the first paragraph of this quote that “truths are independent of human minds”. The second paragraph in this quote tries to double down on explaining or justifying the claim, but it was lead to the wrong conclusion when it supposed an “omniscient and omnipotent observer”. Sean Carroll even said on the first page of the essay that he doesn’t believe that an omniscient observer exists or can exist. Since there are no omniscient observers, we cannot conclude that truth is independent of human minds.

I agree with everything else in the essay. I’m going to proceed by quoting my favorite parts from the document.

In this picture, then, mathematics comes pretty close to satisfying the conditions for realism, but falls just a bit short. This is why it is reasonable to contemplate invoking different senses of “reality.” Mathematics is incredibly useful in describing the world, and we think that conclusions derived mathematically can be extremely reliable, but it’s not real stuff in the way the world is.

– Sean Carroll, Reality Realism, page 6

This quote is true. However, independence of truth is not a condition for a field to be “realist”. So, there were only four criteria for mathematics to satisfy to be “realist”, and it only failed to satisfy just one of those four requirements.

But it is unclear how the usefulness of, say, matrices in quantum mechanics provides evidence for the reality of, say, homotopy groups. I would argue that what actually gains credence is the reality of the subject matter of quantitative empirical science – i.e., the world – rather than the tools we use to describe it. This view saves us from awkward decisions about which parts of mathematics are supposed to be real, and which parts of science support them.

– Sean Carroll, Reality Realism, page 7

This was a great paragraph.

But there are also mathematical statements that (at least for a time being) seem to be irrelevant to our descriptions of physical reality, and yet there is a strong temptation to think of them as “true.” We don’t need the concept of a largest even number, or the absence thereof, to actually do physics. But it seems to follow from the rules we have set up for dealing with integers more generally. Some mathematical truths can be thought of as extrapolations away from physical reality, but still based on the same principles that were suggested to us by considering that reality.

Should we consider such truths as evidence for a separate reality for mathematics? One consideration might be that if we didn’t accept mathematical realism, we might expect there to be different, incompatible “truths” that are based on the same (or equivalent) axioms that we deploy in our discussions of physics

But of course, there are such incompatible “truths,” which appear in a variety of ways. One way is simply to consider sets of axiomatic systems that are completely equivalent in those cases when they are describing physical reality, but which might diverge when we extrapolate them farther. As a somewhat trivial example, we can consider the difference between ordinary addition and addition modulo some integer N. If N is sufficiently large, there are no physically realizable numbers (or numerical values for the quantity of a collection of objects) that we could ever add together to reach it. In that case, the two theories would be physically equivalent. There would be no Platonic truth of the matter concerning what answer one would get when adding N-1 to itself. One might object that “addition modulo N” isn’t what one meant by “addition,” but that is a choice you are choosing to make when defining terms, not something that is decided for us by reality.

Perhaps a more conventional example is the Continuum Hypothesis, which is famously undecidable in ZFC (Zermelo-Fraenkel set theory with the Axiom of Choice). The Continuum Hypothesis, which states that there is no set whose cardinality lies strictly between that of the integers and the real numbers, sounds like something a realist would like to be either true or false (as apparently Gödel did, for example). But it turns out that CH can neither be proved nor disproved within ZFC; one is free to add it or to add its negation. Unlike the mathematical realist, the reality realist has no trouble with this observation. The physical world either does or does not contain structures that can usefully be described by numbers with a cardinality in between that of the integers and the reals. We don’t know whether it does or not, but in neither case are we forced to decide about the pre-existing reality of the mathematical idea.

The case for the reality of mathematical propositions might seem most straightforward when those propositions are theorems that could be proven from axioms. That is the case for things like the non-existence of a largest even number, or analogous but less trivial statements. The process of theorem-proving is a purely logical operation, not relying on any features of the physical world. But which axioms we are tempted to label as “true” does depend on physical reality. The fact that the interior angles of triangles add up to 180 degrees may once have seemed like an immutable truth, but we now recognize that it depends on the axioms of Euclidean geometry, and fails to hold in other equally legitimate systems. We are then left with a form of “if-thenism” (Putnam 1967), in which true statements are of the form “if these axioms are accepted, this theorem can be proven,” but a typical mathematical realist wants the proposition in the theorem to be real, not merely the conditional statement.

It is therefore more common for realists to point to statements that cannot be proven from agreed-upon axioms. The Continuum Hypothesis is an example, as are various statements that cannot be proven or disproven according to Gödel’s incompleteness results, as are the “standard” models of something like Peano Arithmetic. In the last case, for example, there is a feeling that we know what the “true” model of the integers looks like, even though we have theorems guaranteeing the existence of non-standard models that satisfy the axioms perfectly well.

As Putnam (1980) points out, this isn’t really a problem for the hard-core mathematical realist, who posits an ability (somewhat ill-defined) by which we can “grasp” which model is the real one. But it is also, as he goes on to emphasize, not a problem for the hard-core anti-realist, who doesn’t believe there is any one “correct” model of any particular axiomatic system. For purposes of this issue, reality realism is in the latter camp. There is, for sure, what the physical world does; some models might be useful in describing that, and some might not. But the set of all models of arithmetic or any other axiomatic system are not divided into the intrinsically “true” ones and the “false” ones. There is merely the question of which models are useful in talking about reality.

– Sean Carroll, Reality Realism, pages 8-10

This is an amazing quote.

Although it is somewhat tangential to our concerns here, talking about reality and the laws of physics naturally leads one to ask why there are laws of physics at all. This is an especially sharp question for the Humean, who thinks that laws of physics are merely convenient summaries of sets of facts, rather than independently-existing concepts with some causal or governing powers. If the world is a collection of facts, why do those facts have so much structure and compressibility?

I have no idea. I bring it up only because it does seem like a legitimate concern for the Humean, or for reality realism more generally. It may be that this is a “why” question without a distinct answer other than the brute fact of the matter, but that seems unsatisfying. The universe never promised to satisfy us, but it’s reasonable to ask whether it could before we entirely give up. – Sean Carroll, Reality Realism, pages 11-12

This is an interesting quote.

Thinking through these issues has caused me to reflect on the extent to which many working physicists are liable to resist thinking about what is “real.” They care about what works, and what can be measured, but will actively avoid questions about what really exists. (This attitude has been expressed to me by multiple physicists in more or less just these words.)

This is a shame, and is a reflection of the unfortunate divergence between science and philosophy. Physicists have, no doubt, been extraordinarily successful at constructing models of the world that work and make accurate predictions, even without caring too much about the underlying reality. But I would suggest two shortcomings of this perspective.

First, reality is intrinsically interesting. I would wager that most physicists first became interested in science because they wanted to better understand the real world, not because they simply wanted to make successful predictions. The latter attitude is inculcated during their training as scientists. There may be an instrumental reason for this, focusing attention on practical/solvable problems, but something of the initial motivation is lost.

Second, reality is potentially useful. That is, even if one just wants to be a hard-headed model-building scientist, there are angles and insights that might only come from thinking hard about what is real. The fact that physicists don’t agree on the fundamental ontology of quantum mechanics, nearly a century after the formulation of the theory, is a case in point. We don’t know for sure, but this lack of agreement could be holding us back in the search for a theory of quantum spacetime and ultimate unification. It wouldn’t be completely surprising if the nature of reality played an important role in the invention of such theories.

The project of Morality & Mathematics is therefore a crucially important one, for reasons in addition to the obvious importance of understanding the status of moral claims. We need to be able to separate what is real from what is not, and what precisely that means. Although I am an anti-realist about both morality and mathematics, I do appreciate the force of some of the arguments for realism. I look forward to changing my mind if a sufficiently convincing argument comes along. – Sean Carroll, Reality Realism, page 12

This was interesting.

6.2. Philosophical Mathematics

Nowadays, we have branches of mathematics that didn’t exist in the past that can be used to answer philosophical questions. This is a list of philosophical topics that can be better understood by using some branch of applied mathematics:

- Free Will and Determinism: Chaos Theory.

- Time: Temporal Interval Logic.

- Epistemology/Structure of Knowledge: Classical Logic.

- Evidence/Certainty: Evidential Logic.

- Ethics: Deontic Logic.

- Rational Egoism: Game Theory.

- Moral Relativism: Game Theory.

- Philosophy of Information: Graph Theory.

- Language: Formal Language Theory.

- Language Semantics: Logic & Set Theory.

- Philosophy of Music: Set Theory, Abstract Algebra, Numbers, Series, Category Theory, Topology.

- Physics: Calculus, Partial Differential Equations, Linear Algebra, Etc.

- Aesthetics: Mathematical Beauty.

- Axiological Rankings of Value: Binary Relations.

- Calculation of Prices, Economic Values, IQ Scores, etc: For some components of land value, Calculus can calculate land value approximately as a gradient of value that stretches from urban centers and the suburbs out to the rural areas.

And of course, there are also all the situations where mathematics can be used to model real-world phenomenon and thus increase our understanding of them.

Footnotes:

Input is usually provided by biological sensors when unspecified, but it could also be a model or representation, or an imagined set of premises.