Demurrage Currency FAQs

For A Better World

Note: This FAQs is a work in progress. For now, most of the text on this page was written by Josh Sidman’s answers on r/SilvioGesell, combined with my own answers and copy-editing.

If you would like to read or watch a more structured essay or crash course that would answer many potential questions in a more structured format, then we recommend the following:

- Wikipedia: Demurrage Currency.

- Video: Free Money: An Economic System – Noj Rants.

- Video Playlist: Silvio Gesell: Beyond Capitalism vs Socialism Course.

- Money Gitbook (text-based webpages, based on the video course above).

- Zero Contradictions’ Currency Links.

1. Store of Value Questions

1.1. What is money? What are the current functions of money?

Traditional money performs two main functions in today’s society:

- A medium of exchange: Money performs this function when it changes hands.

- A store of value: Money performs this function when it does not move.

It’s not possible nor reasonable for money to do both, because it’s not possible to fulfill both functions at the same time. To rely on money as both a medium of exchange and as a store of value is a contradiction.

“Only money that goes out of date like a newspaper, rots like potatoes, rusts like iron, evaporates like ether, is capable of standing the test as an instrument for the exchange of potatoes, newspapers, iron and ether. For such money is not preferred to goods either by the purchaser or the seller. We then part with our goods for money only because we need the money as a means of exchange, not because we expect an advantage from possession of the money. So we must make money worse as a commodity if we wish to make it better as a medium of exchange.”

– Silvio Gesell, The Natural Economic Order

Money also functions as a unit of account / measurement, but that function is already implied by “medium of exchange”. Gesellians argue that the only reasonable function of money is to serve as a medium of exchange.

1.2. What is Freigeld? What is demurrage currency?

See: Wikipedia: Demurrage currency.

Freigeld (German: ’free money) and demurrage currency are essentially the same thing. Freigeld has several special properties:

- It is maintained by a monetary authority to be spending-power stable (no inflation or deflation) by means of printing more money or withdrawing money from circulation.

- It is cash flow safe (a scheme is put in place to ensure that the money is returned into the cash flow – for example, by demurrage – requiring stamps to be purchased and periodically attached to the money to keep it valid).

- It is convertible into other currencies.

- It is localized to a certain area (it is a local currency).

The name results from the idea that there is no incentive to store or hoard Freigeld as it will automatically lose its value after some time. It is claimed that as a result, interest rates could decrease to zero.

Types of Currencies, Defined By Backing, Characteristics, Demurrage, Et Cetera

| Commodity | Hard Commodity(ies) | Non-Commodity, No Backing | |

| Hoardable | Hard Currency[1] | Hard Currency | Hoardable Fiat |

| Not Hoardable | Natural Demurrage | N/A | Deliberate Demurrage |

Commodity money that has natural demurrage tends to be strictly demurrage money in practice. By contrast, demurrage currency is implied to be representative money.

1.3. Why should money hoarding be discouraged? Most wealth isn’t stored in money.

That’s usually true, but there are still plenty of wealthy people who hold lots of wealth in cash. For example, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway was holding $300 billion in cash in 2025 February 21.

There is no evidence that currency hoarding occurs, nor do I see how it could possibly be of benefit, in our modern credit-friendly economy.

To the contrary, we don’t have a “credit-friendly economy”. It’s not even close, as a truly credit-friendly economy would have no (pure) interest rates. Interest creates an artificial scarcity of credit in the economy.

Currency hoarding may not occur these days, but it still makes sense to increase the velocity money, since it would make it harder for inflation to occur. When currency hoarding does occur, it’s justified by Pigouvian reasoning to tax money to discourage hoarding.

Furthermore, most of the benefits of demurrage don’t come from discouraging money hoarding. That is a common misconception. The main benefits to demurrage money come from how it would theoretically eliminate inflation, deflation, and interest rates.

1.4. But using money as a store of value is already impossible due to inflation.

But using money as a store of value is already impossible, due to inflation. It seems like the problem this is trying to address isn’t actually a problem in the modern economy. Most rich people hold their wealth in assets like real estate, stocks, bonds, etc instead of liquid cash. So why do we need demurrage currency?

Preventing people from storing their wealth money or hoarding money is not the main goal of demurrage currency. The main goal of demurrage currency is to eliminate interest rates, inflation, and deflation. Preventing money from being used as a store of value is mainly only an issue during recessions when the flow of transactions is lower than they should be. Inflation cannot accomplish this during recessions.

The liquidity preference theory of interest implies the interest rates would disappear when money cannot be used to store value. This raises the question why inflation does not eliminate interest rates when inflation makes it more difficult to store value in money. The answer is the inflation cannot eliminate interest rates because inflation is caused by interest rates.

In order to eliminate interest rates within a monetary economy, it is necessary to prevent currency from being a store of value. The only way to accomplish this is with demurrage currency, a form of money that is designed to decay due to entropy just like virtually all other commodities.

“Only money that goes out of date like a newspaper, rots like potatoes, rusts like iron, evaporates like ether, is capable of standing the test as an instrument for the exchange of potatoes, newspapers, iron and ether. For such money is not preferred to goods either by the purchaser or the seller. We then part with our goods for money only because we need the money as a means of exchange, not because we expect an advantage from possession of the money. So we must make money worse as a commodity if we wish to make it better as a medium of exchange.”

– Silvio Gesell, The Natural Economic Order

1.5. Why should money lose value?

The better question is: Why should money be a store of value?

Most forms of real tangible wealth lose value with the passage of time. Whether that be a car, a bushel of wheat, a computer, a pile of lumber, a warehouse full of steel. All of those forms of wealth lose value with the passage of time.

So why does money behave differently? If money is supposed to be a neutral medium to facilitate the exchange of real wealth, when why does it behave in exactly the opposite manner from real wealth? Why does money increase over time, when the vast majority of forms of real wealth lose value?

1.6. But if currency cannot store value, then people won’t trust it.

Currency does not have to store value long-term, in order to be trusted as a medium of exchange:

- Gresham’s law implies that the least valuable forms of money usually become the medium of exchange.

- Many currencies gain their trust due to government backing. If demurrage currencies were legally backed (perhaps even required for commerce), gaining trust obviously wouldn’t be an issue.

- Fiat is usually terrible for storing value due to inflation, and yet most people and economists were eager to drop the gold standard in favor of fiat. This raises the question why demurrage would be better than fiat. The answer is that demurrage would eliminate interest rates, inflation, and deflation.

- Crypto nerds dislike using Bitcoin as a medium of exchange, even though its fixed money supply and characteristics optimize it for storing value.

- Demurrage currency has had positive results everywhere it has ever been tried.

- Most assets in this world eventually decay to entropy, or they have maintenance costs that are required in order to maintain their value. So if money lost value constantly, people would have to choose to lose value by holding money or by holding assets. It would be more preferable for people to own assets instead. Unlike money, assets help sustain life, reproduction, needs, wants, etc. Money doesn’t loses value merely has an unnecessary benefit to its usage.

Of course, it’s a bad idea for money to lose too much value too quickly. Nobody endorses that.

It’s not necessary for money to store value in order for people to trust a currency. Most assets in this world will eventually decay to entropy, or they have maintenance costs that are required in order to maintain their value. So even if money loses value constantly, people would still trust it as a way to store value. Given such premises, people could choose to lose value by holding money or by holding assets. It would be more preferable for people to own assets instead. Unlike money, assets help sustain life, reproduction, needs, wants, etc.

To be trusted, money only needs to store value long enough to accomplish its only goal, which is to be a medium of exchange. A tight-knit community or a country with strong interpersonal trust would also improve the trust of virtually any currency. Crypto-currency implementations could also enhance the trust and ease-of-use of demurrage currency.

1.7. Would demurrage money reset its value after every transaction?

No, there is no reason for demurrage to “reset” in its value after every transaction. I’ve never heard anyone propose demurrage that resets when it is exchanged, nor did Silvio Gesell ever mention or propose such a thing. The misconception that this would happen at all suggests multiple misunderstandings about how demurrage currency works.

If the value of demurrage money resets every time it changes hands and ownership, then it would de facto be no different from regular money in most cases. Such a feature would probably enable loopholes where people repeatedly shuffle money back and forth between their close friends to make it avoid losing value. This would prevent money from circulating throughout the entire economy as intended. It would also mean that the federal bank wouldn’t know the total amount of expired money in cases where money didn’t circulate fast enough. The federal bank therefore wouldn’t be able to know, calculate, or monitor the money supply. For those reasons, none of the demurrage currencies that are used today or within the past century work(ed) had value resets after new transactions.

Gesell proposed issuing “stamp scrip”. Every scrip had to be dated for the time it was first issued by the government. There were also printed boxes on the back of the bill. Every week or month, a stamp would have to be purchased for a small percentage of the bill’s value (0.1%, 0.4%, etc, depending on the rules of the currency) and placed on the back of the bill in order to ensure that the bill retains its full value. Users would have to continue placing stamps on the backs of the bills in order to keep them valid, regardless of who owns them and how much time has passed since the bills were first issued.

Of course, that only describes how bills would work for physical currency. Nowadays with digital currencies and crypto currencies, demurrage rates would work differently. It is a matter of debate regarding how such systems would work. But in any case, such currency probably wouldn’t “reset” its value after transactions.

1.8. Why is the tax on demurrage currency justified according to Pigouvian principles?

When everybody is hoarding money, especially during a recession, it harms everybody because money is unable to function properly as a medium of exchange, and society is thus unable to reap the benefits of the division of labor. In such cases, there is a tragedy of the commons with respect to saving money, versus circulating money. It makes prefect sense to resolve this game theory problem via a change in government policies, in order to prevent negative externalities.

We can draw an analogy between money and water to articulate the issue of the store of value property. Water can flow, and water can stand still. Flowing water represents money functioning as a medium of exchange. Still water represents money functioning as a store of value.

Let’s imagine that there is a stream with a community of people living on its banks. But this is no ordinary stream. This is a magic stream that enables people to transform the product of their labor into any other good or service that they want or need. The dairy farmer puts his milk into the stream and draws out of it bread, clothing, shelter, and everything else he and his family need in order to live. This magic is the division of labor.

The stream is a vital public resource, and the lives of everyone in the community depend on its flow.

Now let’s say that certain individuals choose to divert the flow of the stream in order to build private ponds. They do this so they will be sure to always have water in case the stream ever stops flowing. What would happen if everyone did this? Obviously it would jeopardize the continuous flow of the stream on which everyone’s survival depends. Furthermore, any time someone saw another person building a pond and diverting water into a private store, they would have an incentive to do likewise. And the more people who build ponds, the stronger is the incentive for others to build ponds too. And, due to the self-reinforcing dynamic of the incentives facing individuals to build ponds, the fear that motivated the construction of ponds in the first place becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Before long, everyone will obey the instinct of self-preservation and build a pond, and the collective consequences of doing so will be to bring about the circumstances against which the precaution of building ponds was meant to guard against.

If the flow of the stream was always continuous and reliable, people wouldn’t have to fear it ever running dry. But now, because of people taking precautions against that possibility, that has now made it a reality. Because of everyone guarding against the flow of the stream becoming unreliable, the flow of the stream has in fact become unreliable. To bring the analogy back to the subject of money, by making the decision to use money as a store of value, we have made it unreliable in terms of performing its primary, life-sustaining function as a medium of exchange. Gesell said “the power of money to effect exchanges, its technical quality from the mercantile standpoint, is in inverse proportion to its technical quality from the banking standpoint.”

Because of the inherent tension between money’s functions as medium of exchange and store of value, the flow of the stream becomes inconsistent. Sometimes too much water is diverted into ponds and the stream runs dry. And other times everyone decides to release their private stores of water all at once and the stream overflows its banks. Silvio Gesell tells us this is because the store of value function is an unnatural, incorrect use of money.

2. Inflation Questions

2.1. How do different schools of economics define inflation?

Different schools of economic thought approach inflation with varying definitions and underlying theories about its causes and mechanisms:

- Classical School: Defines inflation as a general rise in prices caused by an increase in the quantity of money in circulation relative to the quantity of goods and services available. Inflation may be caused by monetary expansion (e.g. increases in gold and silver supply), government debasement (e.g. Reducing the precious metal content in coins), trade imbalances (e.g. Large influxes of gold/silver from colonies or trade surpluses), or implications from Say’s Law.

- Neo-Classical School: Defines inflation the same way as the classical school, but proposes different causes. Inflation may be caused by velocity changes (variations in the speed of money circulation), expectations (recognition that anticipated inflation can become self-reinforcing), and market imperfections (acknowledgment that monopolistic elements can contribute to price rises).

- Keynesian School: Takes a broader view, defining inflation as a sustained rise in the general price level that can result from multiple factors including demand-pull (excess aggregate demand), cost-push (rising input costs), or built-in inflation (expectations and wage-price spirals). Keynesians emphasize that inflation can occur even without monetary expansion if other economic pressures exist.

- Post-Keynesian School: Emphasizes inflation as primarily driven by institutional factors, market power, and social conflict over income distribution. They define inflation as often originating from markup pricing by firms with market power rather than purely monetary or demand factors.

- Monetarist School: Defines inflation as “always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. Monetarists view inflation as primarily caused by excessive growth in the money supply relative to economic output. Their definition focuses on sustained increases in the general price level resulting from too much money chasing too few goods.

- Austrian School: Defines inflation specifically as an increase in the money supply itself, rather than rising prices. Austrians argue that rising prices are merely a symptom of monetary inflation. They distinguish between monetary inflation (the cause) and price inflation (the effect), emphasizing that not all price increases constitute true inflation.

- Supply-Side Economics: Focuses on inflation as often resulting from supply constraints, regulatory burdens, or production costs rather than demand factors. Their definition emphasizes how barriers to production can drive sustained price increases.

- Chicago School: Similar to monetarists but with greater emphasis on rational expectations. They define inflation as sustained price level increases that become embedded in economic expectations, making the inflation rate partly self-fulfilling.

- Freiwirtschaft School: Inflation is defined as a sustained rise in the general price level. Inflation is mainly caused by the existence of interest rates, which are created due to the artificial scarcity of money as a medium of exchange, which is caused by the usage of money as a store of value.

Each school of economics disagrees significantly on whether the root cause of inflation is monetary, structural, institutional, or expectational. Overall, the general consensus is that inflation is a sustained increase in prices.

2.2. How is demurrage currency different from inflation?

There are multiple differences between demurrage currency and inflation. The most important difference between demurrage and inflation is how they affect economic recessions differently:

- Inflation is defined as “a general rise in prices”.

- During recessions, prices tend to fall.

- When prices fall and we can expect them to continue falling, commerce falls too. (because why would anyone buy something today when they will be able to buy it cheaper tomorrow?)

- Recessions thus face a game theory problem: we want to increase commerce, but nobody wants to increase commerce if prices will continue to fall.

- If prices are falling, then there is no inflation, by definition.

- If there is no inflation, then there are no penalties for withholding money from circulation during a recession.

- Thus, holders of money are rewarded for withholding their money from circulation during periods of falling prices. (because they are able to buy the same goods & services at lower prices in the future.)

- This makes it difficult to increase circulation and end the recession.

- By contrast, demurrage currency would encourage people to keep commerce going during recessions, unlike inflation. If money continues to lose purchasing power (even at a slow rate), then people will use it sooner rather than later.

There are other differences as well:

- Demurrage is consistent and predictable, whereas inflation is not. For example, if the demurrage rate is, 6% annually, then money loses 1/2% of its purchasing power per month every month, regardless of whether the economy is expanding, contracting or remaining the same. Inflation, on the other hand, is inconsistent and unpredictable. Sometimes it is high, sometimes it is low, and sometimes it is negative (i.e. deflation).

- Demurrage operates only on outstanding units of currency, not on newly issued money or money that will be issued in the future, whereas inflation affects both outstanding currency as well as money issued in the future. So with demurrage, if a laborer earns a salary of $50,000 per year, that salary will buy the same quantity of goods & services today, in one year, and in five years (assuming no inflation). Whereas inflation affects the purchasing power of outstanding money as well as future money. 5% demurrage does not diminish what workers can buy with their future paychecks. Whereas 5% inflation means that their future paychecks buy less and less as time goes by.

- Inflation benefits borrowers at the expense of lenders, whereas demurrage does not. The effect of demurrage on borrowers, on the other hand, depends on what they do with the money. If they spend it (either for consumption or investment), they do not bear the cost of demurrage. If they hold onto the money, then yes, they lose due to demurrage, but why would anyone borrow money just to hold onto it?

2.3. What should the inflation target be?

It should be 0%. The one and only goal of monetary policy in a Gesellian system would be price stability. So-called “good inflation” of 2-3% in our current system is a symptom of an irrational form of money that doesn’t circulate properly. Inflation is like a drug that needs to be administered in order to keep it circulating. But that drug is inconsistent, imprecise and has harmful side effects.

2.4. Why would demurrage end inflation? Why not return to the gold standard instead?

A limited currency supply seems superficially appealing because the endless expansion of the current fiat money supply is obviously unsustainable, but it would ultimately fail to produce enduring price stability.

The problem is that the main two functions of traditional money (medium of exchange and store of value) are incompatible with each other. When money becomes better at one function, it becomes worse at the other function. If we used a currency with a fixed money supply (e.g. Bitcoin), it would be great at storing value, but it would also be terrible at being a good medium of exchange (i.e. terrible at fulfilling the whole reason why money exists at all in the first place).

If anything, hard money would guarantee price instability, since it would ensure that prices always fall when they’re are already falling and always rise when they’re already rising.

By contrast, demurrage currency would ensure that money is always circulating at the maximum possible velocity. If money is always circulating at the maximum possible rate, then where could inflation possibly come from, if the quantity of money remains the same?

2.5. How would demurrage affect deflation?

First, we must define the word “deflation”. The generally accepted definition is “a fall in the general price level”, although others define it as “a decline in the money supply”. We’d say that the latter definition is incorrect. But the main thing is to be sure we’re being clear and consistent with how we use the word.

Demurrage does gradually reduce the money supply (which, again, is not the definition of deflation as I understand it). It thus usually necessitates an offsetting increase in the money supply, in order to maintain stable price levels. Also note that due to the increased velocity of money, less money would need to be issued overall.

There are different ways this could be accomplished. One way would be for government to create new money and put it into circulation by spending it on public works. The appropriate level of such spending would be determined by the price level. If prices decline, government spending of newly created money would need to increase. If prices rise, it would need to decrease. And once again, according to the generally accepted definition of the word “deflation”, if the price level is stable, then there is no deflation.

Another mechanism for adjusting the money supply to offset demurrage and maintain a stable price level is a Universal Basic Income (UBI). There’s plenty of scope for debate about which of these approaches is better. Personally, we prefer the first.

2.6. Why do prices tend to fall during recessions without demurrage money?

During recessions, prices tend to fall due to several interconnected economic mechanisms:

- Reduced consumer demand - As unemployment rises and income uncertainty grows, households cut back on spending, especially for non-essential items. This drop in demand puts downward pressure on prices as businesses compete for fewer consumer dollars.

- Excess production capacity - With decreased demand, businesses find themselves with unused production capacity. To maintain some revenue flow and cover fixed costs, they often lower prices to stimulate sales.

- Inventory liquidation - Companies facing cash flow problems may need to quickly convert inventory to cash, leading to discounting and promotional offers.

- Business survival strategies - In the struggle to stay afloat, businesses may cut prices to maintain market share and cash flow, even at reduced profit margins.

- Credit contraction - Tighter lending conditions make it harder for both businesses and consumers to borrow, further reducing spending and investment.

- Asset bubbles - Recessions are often accompanied with and (partially) caused by popping asset bubbles.

- Deflationary expectations - When people begin to expect prices to fall further, they may delay purchases, creating a self-reinforcing cycle that puts additional downward pressure on prices.

This price deflation is a classic symptom of economic contraction, though the severity varies greatly between different recessions and across different sectors of the economy.

2.7. At which monetary level would demurrage take effect? M0, M1, M2, M3?

Those monetary aggregates probably would not exist under a Gesellian system. The Ms describe a system in which most money is created by the private banking sector. A Gesellian currency would be issued by the government, so the systems for measuring money would have to be redefined. And the whole architecture of banking and financial intermediation would have to be re-conceived from the ground up.

3. Interest Theory Questions

3.1. What is interest?

These four components make up the total interest rate:

- Pure (Risk-Free) Interest:

- The basic rate charged for just deferring consumption

- Represents the “time value of money”

- What a lender would charge in a perfectly safe environment

- Often approximated by government securities like U.S. Treasury bills

- Compensates lenders for giving up current purchasing power

- Risk Premium:

- Additional compensation for taking on risk

- Covers potential default/non-payment

- Higher for riskier borrowers/investments

- Varies based on creditworthiness, collateral, economic conditions

- Larger risk premiums for things like junk bonds vs. government bonds

- Expected Inflation/Deflation:

- Adjustment for anticipated changes in purchasing power

- Protects lender from loss of real value due to inflation

- Can be negative in cases of expected deflation

- Based on market expectations of future price levels

- Critical for maintaining real returns over time

- Administrative Costs:

- Covers the operational expenses of lending

- Includes costs of:

- Processing applications

- Servicing loans

- Maintaining records

- Collection efforts

- Regulatory compliance

- General overhead

The total interest rate charged would be the sum of all these components, though they’re not always explicitly broken out in practice.

3.2. How does interest relate to Gesellian theory?

Silvio Gesell’s theory of money and interest presents a unique perspective on interest, centered around his concept of “free money” (Freigeld). Here are the key aspects of Gesellian theory in relation to interest:

- Natural Economic Order:

- Gesell believed interest was not a “natural” phenomenon but an artificial construct

- He argued money should “rust” like other commodities (lose value over time)

- This concept led to his proposal for “stamped money” that depreciated at a fixed rate

- Critique of Traditional Interest:

- Gesell argued traditional interest creates unfair advantages for money holders

- He believed money’s ability to be hoarded without loss created artificial scarcity

- This hoarding power allows money owners to demand interest from productive enterprises

- Liquidity Premium:

- Gesell recognized money has a natural advantage over goods due to its:

- Durability

- Portability

- Universal acceptability

- This advantage creates a “liquidity premium” that holders can charge for parting with money

- Gesell recognized money has a natural advantage over goods due to its:

- Proposed Solution:

- Demurrage: A holding fee/carrying cost on money

- Regular stamps required to keep money valid

- Encourages circulation rather than hoarding

- Aims to eliminate the basic interest component

- Practical Applications:

- The Wörgl experiment in Austria (1932-1933) used Gesell’s ideas

- Various local currencies have incorporated demurrage features

- Some modern digital currencies experiment with negative interest concepts

Gesell’s theories influenced later economists including John Maynard Keynes, who discussed them in his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.

3.3. What would be the benefits of eliminating pure interest?

Note: This section is a work in progress. It takes time to write stuff.

Eliminating pure interest rates would lower the opportunity costs to investment and innovation, reduce or eliminate inflation, incentivize more environmentally friendly resource consumption, and eliminate the unsustainable growth imperative.

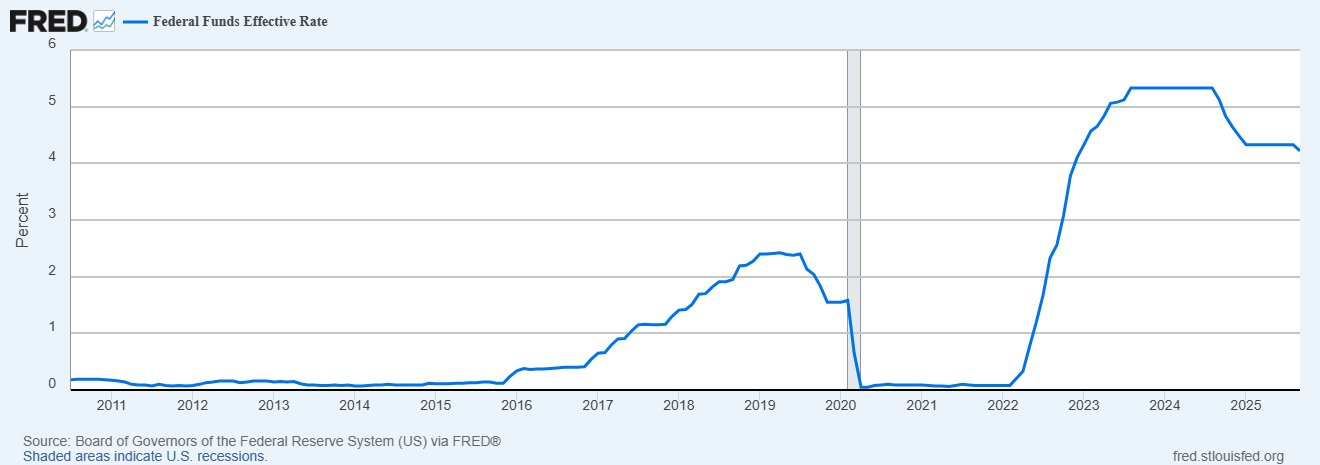

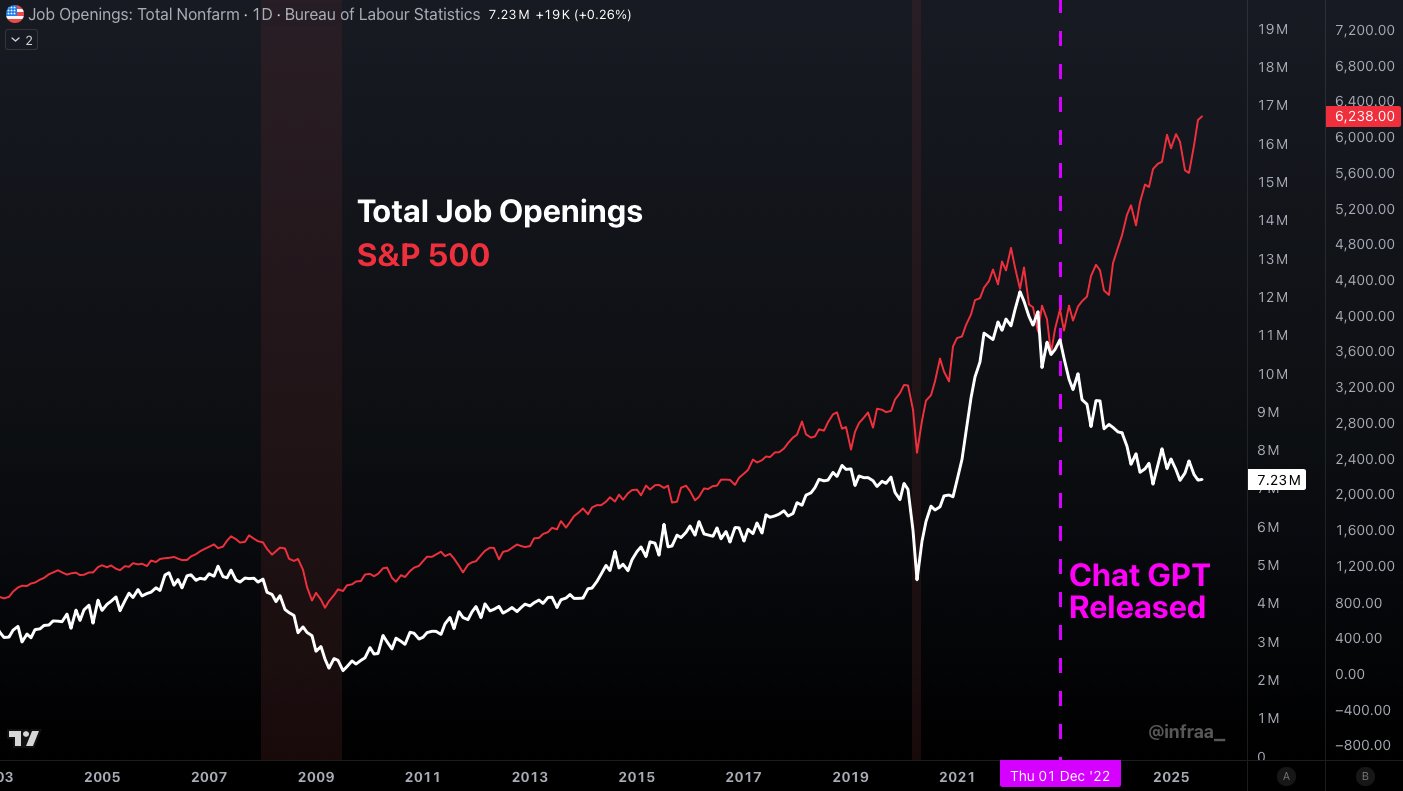

Consider how the rise in interest rates during 2022 negatively affected the white-collar job market.

Read More: Wikipedia: Demurrage currency #Interest rates.

3.4. Why is the liquidity preference theory of interest superior to productivity theory?

How valid is the critique that the goods that Gesell chose in the Robinson Crusoe parable are cherry-picked? Are they unrepresentative of most real world cases that involve lending and borrowing?

The goods that Gesell chose in the Robinson Crusoe parable are not cherry-picked. The phenomenon of goods/services losing value with the passage of time is nearly universal, even for goods that are not subject to rapid physical decay. The story covered at least two ways how commodities can lose value of time:

- If the wheat lost value, it would be mainly due to physical decay, which applies to all food, livestock, and living things.

- If the buckskins lost value, it would be mainly due to a lack of maintenance.

Physical decay is not the only cause of value erosion. Obsolescence is also a big part of the picture. For example, you could perfectly preserve the physical attributes of a car, a computer, an iPhone, etc, and they would still lose value with the passage of time due to the introduction of newer models.

Storage costs, security, insurance, etc are also contributing factors. After all, if you chose to store your wealth in the form of a brand new car, where would you keep that car? How would you ensure it doesn’t get stolen? How would you make sure it doesn’t get damaged by falling branches or hail? So, money’s advantage in terms of immunity to physical decay does not fully encompass its superiority to real goods and services as a form in which to store wealth.

In list format, the story failed to give examples of goods that lose value due to:

- Obsolescence or Planned Obsolescence.

- Storage Costs.

- Other Costs Of Maintenance.

- Time-Sensitive Information (applies to intellectual property, newspapers, stocks, bonds, etc).

- Et Cetera.

And generally speaking, labor cannot be stored at all. Therefore, the imbalance between the impulsion to sell goods and services vs the lack of impulsion to get rid of money is a correct description of one of the primary causes of interest. However, it may also be accurate to say that liquidity preference is not a complete explanation of the entire phenomenon of interest.

But I would definitely not agree that productivity theory is a better explanation of interest. Productivity theory is really only half of a theory, because it completely ignores the benefits that owners of capital receive through lending it out. This is one of the important takeaways of the Robinson Crusoe parable.

3.5. What’s wrong with the time preference theory of interest?

Time preference means that people prefer to have a good or service sooner rather than later, on average. When this is true, time preference contributes to positive interest rates. Interest is supposedly offered as a reward for postponing consumption.

However, the law of marginal utility counteracts time preference. When one has enough of everything that they need, their next preference would be to have enough of everything that they need in the future. If many people have enough of everything, or when there are a few extremely rich people, the law of marginal utility may overcome the time preference, and interest rates can be negative.

People who subscribe to the time-preference theory have the causation backwards. It’s not that interest exists because people prefer to consume sooner rather than later. It’s that people behave as if they prefer to consume sooner rather than later because interest exists.

For example, when there is a choice between 10,000 loaves of bread now or one loaf of bread each day for the next 10,000 days, most people prefer one loaf of bread every day for the next 10,000 days. Most people will even prefer one loaf of bread each day for the next 1,000 days to 10,000 loaves of bread now, which implies a steep negative real interest rate. This is because bread spoils. No one can use 10,000 loaves of bread within a day. It also applies to durable goods. Most people would prefer to have a new car now and a new car in ten years’ time, instead of having two new cars now.

Consider another example. Imagine you run a lumber company. Let’s think about how interest affects your incentives regarding when to cut down trees. Trees grow faster when they’re young and more slowly as they get older. As soon as the growth rate of a tree falls below the interest rate, there is a financial incentive to cut the tree down. If you pay 7% interest on capital but you have a tree that is only growing at 5% per year, then it is a bad financial decision not to cut it down. Note that the same logic applies even if you don’t borrow money to finance your business, because interest also represents the opportunity cost of any productive investment. If you could be earning 7% by lending your money for interest, it is a bad financial decision to keep your wealth tied up in a tree that is only growing by 5% annually.

But what if the interest rate was 3%? Or 2%? Or 0%? How would that affect the incentives to cut down trees? At a zero interest rate, it would be reasonable to let a tree keep growing until it reaches the end of its growth cycle. At a 0% interest rate, a tree growing at 1% per year would still increase the owner’s wealth.

(This isn’t to say that no one would ever cut down a tree that was still growing if interest fell to 0%, but in a zero-interest environment, non-neutral money would not create an artificial inventive to behave in a short-term focused way.)

Interest is the opportunity cost of any productive investment. If holders of money can earn more by lending to the government, they will not choose to make their money available to productive enterprise. Therefore, in order to attract funding, prospective productive enterprises need to offer projected returns in excess of the rate of interest. Prospective investments which can’t offer projected returns in excess of the rate of interest do not receive funding.

So to recap, current time-preference is not necessarily an inherent part of human nature. It is a consequence of an irrational form of money, which creates an artificial incentive structure that encourages short-term thinking.

A well-known Gesellian economist, Felix Fuders, makes the argument that our unnatural form of money is the main driver of unsustainable behavior. If we want to promote a more sustainable future, then the number one thing we should do is to institute a more natural form of money, as proposed by Silvio Gesell.

3.6. How would banks profit from loaning money, if interest rates are eliminated?

Interest rates generally include a portion for covering the banks’ administrative costs and profits for storing and lending money. This type of interest would still exist in a demurrage money economy, so banks would still be able to profit from loaning money under a demurrage monetary system. It is the pure, risk-free interest rates that would no longer continue to exist.

3.7. Aren’t interest rates necessary to incentivize borrowers to pay back loans?

Aren’t interest rates on loans necessary in order to incentivize borrowers to eventually pay back the loans, in order to prevent the interest from growing?

No, not necessarily. A better way to incentivize borrowers to repay their loans would be penalize them with legal penalties, if they do not repay their loans by a certain date like say two, five, or ten years or so.

4. Debt, Lending, And Credit Questions

4.1. Would demurrage money need to be backed?

Gesellian money would not need backing. He stated that clearly in his book. Backing is primarily meant to enhance money’s properties as a store of value. But the whole idea of Gesellian money is to make it unsuitable for use as a store of value. In that sense, backing is counterproductive.

In Gesell’s view, the primary cause of inflation is the unstable and unpredictable velocity of money. Demurrage is meant to solve that problem by incentivizing the steady circulation of money under all economic conditions. If velocity is stable, maintaining a stable price level becomes much easier. The reason monetary policy is so difficult with our current form of money is because of unstable monetary velocity. This is where the term “pushing on a string” comes from. It refers to a situation like after the 2008 crisis in which the world’s central banks created massive amounts of new monetary reserves but were powerless to make those reserves circulate. Regulating the price level via adjustments in the money supply with unstable velocity is extremely difficult and imprecise.

4.2. How would credit work under demurrage currency?

Here’s how credit could function under a demurrage currency system:

- Interest Structure:

- Lower base interest rates due to reduced hoarding

- Borrowers might receive demurrage rebates

- Credit costs would reflect:

- Risk premium

- Administrative costs

- Inflation expectations

- Minus demurrage offset

- Lending Dynamics:

- Banks would face pressure to lend

- Holding reserves incurs demurrage cost

- More active credit markets

- Shorter loan terms might be preferred

- Emphasis on productive lending

- Credit Creation:

- Banks still create credit through loans

- Modified fractional reserve system

- Credit money subject to demurrage

- New accounting methods needed

- Balance sheet adjustments

- Types of Credit:

- Business loans prioritized

- Consumer credit modifications

- Mortgage restructuring

- Investment credit changes

- Trade credit adaptations

- Risk Management:

- New risk assessment models

- Modified collateral requirements

- Different default calculations

- Portfolio management changes

- Insurance adaptations

- Institutional Framework:

- Reformed banking regulations

- New credit monitoring systems

- Modified credit ratings

- Changed reserve requirements

- Updated lending guidelines

- Practical Implications:

- Faster credit turnover

- More productive lending focus

- Reduced speculation

- Changed savings patterns

- New financial products

4.3. How would debt and lending work under Freiwirtschaft?

Under Silvio Gesell’s Freiwirtschaft (“free economy”) system, debt and lending operate fundamentally differently from conventional monetary systems due to the introduction of Freigeld (“free money”), a currency designed to lose value over time. Here’s how debt and lending function under this framework:

- Freigeld: Money with Demurrage

- Demurrage (Decaying Value): Freigeld loses value periodically (e.g., via required stamps to keep it valid), incentivizing rapid circulation rather than hoarding[2]. This “stamp scrip” system imposes a cost on holding money, forcing users to spend or invest it.

- Impact on Lending: Since money depreciates, lenders cannot profit from merely holding funds. Interest rates theoretically approach zero, as there is no advantage to liquidity (storing money)[2][3]. Gesell aimed to eliminate the “basic interest” (liquidity premium) that rewards hoarding.

- Interest Rates Align with Real Capital Returns

- Loan Interest vs. Basic Interest: Gesell distinguished between two types of interest:

- Basic Interest (liquidity preference): The premium paid to prevent hoarding. Under Freigeld, this would vanish due to demurrage.

- Loan Interest: Reflects the return on real capital (e.g., machinery, infrastructure). Gesell argued loan interest should equal the productivity of physical assets[3].

- Transition to Zero Interest: Gesell acknowledged that loan interest would persist until capital abundance eliminates scarcity. Over time, unimpeded investment in productive assets would drive loan rates to zero[3].

- Loan Interest vs. Basic Interest: Gesell distinguished between two types of interest:

- Debt Dynamics

- No Incentive for Hoarding: With demurrage, lenders cannot profit from withholding money. Debtors are incentivized to borrow for productive investments, as idle money loses value.

- Risk and Stability: The system aims to stabilize economies by preventing deflationary spirals caused by hoarding. Money circulates faster, reducing unemployment and wasted resources[2].

Comparison to Conventional Debt Systems

| Aspect | Conventional Debt Systems | Freiwirtschaft |

|---|---|---|

| Interest Purpose | Compensates for time, risk, and liquidity preference. | Eliminates liquidity preference; loan interest tied to real capital returns. |

| Hoarding | Rewarded via interest, leading to economic stagnation. | Penalized via demurrage, ensuring continuous circulation. |

| Debt Sustainability | High debt levels risk insolvency and restrict growth. | Debt supports productive investment, as hoarding is disincentivized. |

| Monetary Stability | Vulnerable to deflation (hoarding) or inflation (over-issuance). | Aims for price stability via spending-power-stable Freigeld[2]. |

Summary: Under Freiwirtschaft, debt and lending are reshaped by demurrage, which eliminates the liquidity premium and forces money into circulation. Gesell envisioned a system where:

- Interest rates reflect only real capital productivity, not hoarding incentives.

- Debt fuels productive investment rather than speculative hoarding.

- Economic crises caused by money withdrawal (deflation) are mitigated through enforced currency circulation.

This radical approach seeks to align financial incentives with tangible economic activity, prioritizing resource utilization over financial speculation.

4.4. Who does hard money benefit under different economic conditions?

Note: This section is a work in progress. It takes time to write stuff.

In the eggs and beef thought experiment mentioned in lecture #4, the owner of the beef benefits from the existence of money, since it enables him to overcome the fragility and vulnerability to spoilage of his beef. Why? Because he can sell his beef immediately to someone else (e.g. grocery stores, restaurants, etc), collect his profit, and now his wealth is secured. It is now the grocery stores, restaurants, etc which will suffer if they cannot sell enough beef containing products. During recessions, the producers and sellers of decayable goods are harmed by the nature of hoardable money. That includes the person who produces the beef (the producers), and anyone who might sell the beef after storing and processing it (grocery stores, restaurants, etc).

When the medium of exchange is scarce (i.e. money is not trading hands because it is functioning as a store of value), traders will pay to rent it (interest), which acts as an impedance to trade. In stable or deflationary environments, interest is a net transfer of wealth from debtor to creditor. Under inflationary environments, interest is a net transfer of wealth from creditor to the debtor.

| Economic Outcomes | Producer of Decayable Goods / Lenders | Buyers / Borrowers |

| Healthy Circulation | Hard money can benefit producers | Hard money creates interest, which harms borrowers |

| Recession | Hard money can harm producers, when their inventory decays | Hard money can benefit buyers, if prices fall |

Without the existence of money, the borrower and the lender are on fair ground, so the borrowing transaction equally benefits both parties. In the existence of fiat money, the tables turn. The lender benefits from being able to receive interest, while the lender is harmed during recessions, if and only if they are producing or selling decayable goods. However, if the lender was not loaning something that is particularly vulnerable to entropy, then perhaps the lender could benefit due to deflation, which tends to happen during recessions.

4.5. If storing demurrage currency in a bank would prevent it from losing value, then why would demurrage retain a high velocity of money?

Note: This section is a work in progress. It takes time to write stuff.

i

5. Addressing Objections

5.1. What if people resort to traditional currencies, instead of demurrage?

It’s unlikely that this would happen, due to Gresham’s Law. For more information, see:

Anwar, Ahmed (December 2020). “From Keynes’ Liquidity Preference to Gesell’s Basic Interest” (PDF). Discussion Paper Series. 299. University of Edinburgh School of Economics: 29.

5.2. Would demurrage currency affect resource consumption?

5.3. Would demurrage currency encourage planned obsolescence?

If anything, demurrage currency would disincentivize planned obsolescence.

The existence of interest rates are a consequence of hoardable money. Interest artificially limits the creation of productive capital. Since holders of excess money have the option to earn a risk-free return by lending to the government, this means prospective investments in newly formed capital will not receive funding unless they can provide projected returns significantly in excess of the risk-free interest rate. That means less companies get the investments they need to fund their operations, and as a result fewer companies exist than would be the case in a “natural economy” with demurrage money.

So the replacement of conventional money by demurrage money would lead to a huge amount of new investment in productive capital, since people who currently hold trillions of dollars in unproductive government debt will need to look for other places to put their money. That would lead to increased competition among producers of goods & services, resulting in higher quality and lower prices.

In short, demurrage currency would vastly increase competition, which would reduce planned obsolescence. Companies will have to make better products or they will lose customers. Demurrage money would lead to more competition, and thus cheaper higher quality goods and services.

This question also overlooks that the purpose of demurrage money is not to prevent people from saving wealth. It is to prevent them from using money as the vehicle for doing so. Saving wealth is still important and necessary.

So how would people save wealth without saving money? They would lend money (but without interest). Instead of holding onto cash that loses value at 5% annually, savers would lend their money to someone who has a current use for it. The borrowers would repay the lenders the full principal of the loan in the future. And the lender would thereby avoided the erosion of purchasing power, due to demurrage. In other words, the lenders would have saved.

Taxing natural resources would also discourage planned obsolescence.

6. How Would Freiwirtschaft Affect Different Interest Groups?

6.1. How would Freiwirtschaft affect the rich?

Note: This section is a work in progress. It takes time to write stuff.

6.2. How would Freiwirtschaft affect the middle class and poor?

Note: This section is a work in progress. It takes time to write stuff.

6.3. How would Freiwirtschaft affect the FIRE movement?

Note: This section is a work in progress. It takes time to write stuff.

6.4. How would Freiwirtschaft affect trade deficits?

Note: This section is a work in progress. It takes time to write stuff.

6.5. How does demurrage currency compare to UBI?

Note: This section is a work in progress. It takes time to write stuff.

7. Implementation Questions

7.1. What is Freiwirtschaft? Who was Silvio Gesell?

See:

- Wikipedia: Freiwirtschaft.

- Wikipedia: Silvio Gesell, the creator of Freiwirtschaft. Gesell was proto-Keynesian.

7.2. What is Freiland? How is Freiwirtschaft related to Georgism?

7.3. Would free money be applied only regionally?

Gesell intended demurrage money to be implemented at a national and international level. Personally, while I think his proposal is sound, it’s hard to imagine mobilizing the political will in today’s world to get an entire country to change to a new form of money. That’s why many modern Gesellians have chosen to focus on local and alternative currencies. Its much easier to envision a realistic path forward implementing demurrage on a local/community level, but I consider that an intermediate step on the way toward global adoption. If its viability can be proven on a local level, that can help mobilize support for adoption on a larger scale. But, to repeat, Gesell never discussed local/alternative currencies. He was focused exclusively on national and international adoption.

What will ensure the value of the money is trusted? In Wörgl, didn’t the mayor use 40,000 schillings as backing for the demurrage currency he implemented?

As Gesell said, there is no need for backing to “ensure the value” of money. The fact that money is the essential precondition for the functioning of the division of labor is all the “backing” money needs.

Yes, in Wörgl they deposited 40,000 schillings in the bank as “backing”. Worgl happened after Gesell died, but I’m quite sure he would have said the backing was completely unnecessary.

7.4. How would Freiwirtschaft be implemented in today’s world?

There’s a consensus that land reform without money reform is possible. However, money reform without land reform is not possible. If people can’t store value and wealth within money, they would naturally choose to store wealth in land instead, which would worsen land speculation and the problems caused by private land ownership. Hence, monetary reform via demurrage currency would require nationalizing all land ownership, in order for it to achieve the intended goals and be effective.

Note that it may not be necessary to tax land at 100% of its value in order to discourage people from storing their wealth and land. It’s possible that even a relatively modest amount of land value taxation may be all that’s required in order for widespread demurrage currency on a large-scale to succeed as intended. The LVT rates would just have to high enough to discourage people from resorting to storing wealth in land, rather than other assets.

Footnotes:

Hoardable commodity currency would have to be hard currency. Hard currency is naturally hoardable, since hard currencies are immune to naturally depreciating in value.